It looks unfortunately very likely that San Francisco’s last surviving movie palace, the 102-year-old Castro Theatre, will soon no longer fit that description. Though its days as a repertory cinema already ended a while back, even annual festivals and other film events that had traditionally taken place there are now looking to move elsewhere, given expected physical alterations and booking policies by the new corporate owner. (For instance, Noir City has already departed for Oakland’s Grand Lake Theatre, where it will again take place this next January.) There will no doubt continue to be one-off revival showings and other projection-focused happenings. But the Castro’s future focus will be on live entertainment.

Ergo, all the more reason to hie thee there for A Day of Silents this Sat/3, a day-long affair that may well prove to be one of the last such happenings to grace this venerable screen. San Francisco Silent Festival’s late-on-the-calendar addendum to their expansive main yearly exhibition event (scheduled for April 10-14 at SF’s Palace of the Fine Arts) offers no less than six complete programs. They span a gamut of genres and nationalities, nearly all drawn from the pre-“talking” art form’s peak decade of the Roaring Twenties.

A century has passed, and you might ask: Have movies improved overall since then? Well, opinions may differ, but we’d politely suggest the correct answer is: Hell, no. I mean, it’s pretty hard to imagine the Marvel Cinematic Universe surviving as long as vintage classics by Harold Lloyd or Ernst Lubitsch—or wanting to witness a world in which they are equally considered masterworks of an art form.

It’s a starry lineup this weekend, starting with the 10am all-cartoon bill “Of Mice and Men (and Cats and Clowns).” The 10 shorts here chart animation’s rapid development over two decades’ course, with Emile Cohl’s 1908 Fantasmagorie looking as if its moving figures were drawn on a chalkboard, while Windsor McCay’s almost unpleasantly vivid How a Mosquito Operates (1922)—about a persistent bloodsucker and a sleeping man—has a more elegant, but also simple line-drawing style. A revelation is the same year’s Adam Raises Cain. Its fanciful glimpse of prehistoric life gets depicted in elaborate silhouette by puppeteer Tony Sarg, a remarkable if now little-remembered talent.

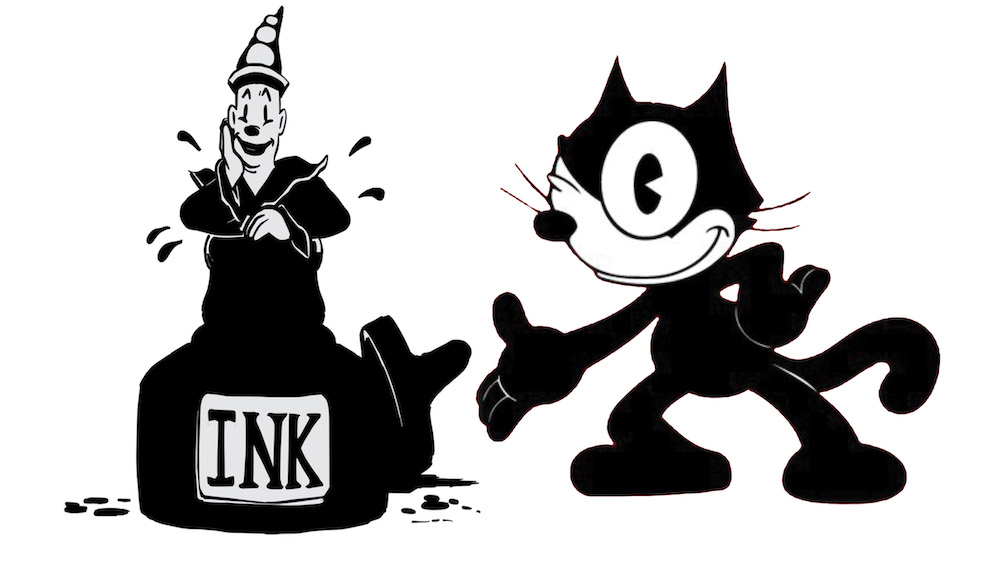

We then move into the realm of still-famous animators who built their own studios and created signature characters. Paul Terry (whose career stretched into the mid-1950s, including the adventures of Mighty Mouse and Heckle & Jeckle) contributes 1923’s rowdy Amateur Night at the Ark. The Fleischer brothers’ surreal humor is on display in Bed Time, A Trip to Mars and Vacation, all showcases for their star personality Koko the Clown—though he’d end up taking a back seat once they introduced Betty Boop.

Pat Sullivan and Otto Messmer’s Felix the Cat (seen here in Felix Grabs His Grub and Sure-Lock Homes) was by far the most popular cartoon character of the era, a popular phenomenon without rival until Mickey Mouse came along. Even that’s rodent’s eventual creator, Walt Disney, made his own critter protagonist a Felix lookalike in the 1926 Alice’s Balloon Race, which like several films here incorporates some live-action footage to antic effect.

Despite their rapidly escalating technical sophistication, even the best of those silent ‘toons basically just string together slapstick gags. Operating on a different level of comedic expertise altogether was the German director Lubitsch, whose career got launched internationally by a series of widely exported spectaculars that made an even greater sensation of his star, Polish vamp Pola Negri. Before both answered Hollywood’s siren call—albeit on diverging paths, his proving the greater long-term success—they departed from the spicy costume dramas of prior collaborations with 1921’s The Wildcat.

A very funny burlesque of those heavy-breathing exotic romances, it has Negri as the whip-wielding wild-child daughter of the chief to a bandit gang living in mountain caves. She finds herself unexpectedly besotted by the incorrigible playboy lieutenant (Paul Heidemann) newly assigned to the area’s remote military fort. (When he leaves his prior post, the entire town’s female population turns up to bid a swooning farewell.) The Keystone Kops-like bandits’ plan to rob the fort itself ends up, naturally, complicated by amour. At first amusing, then often downright hilarious, the movie is full of fun even on the design level, with gimmicky image framings, fabulously whimsical sets for the fort interior, and an utterly gratuitous dream fantasy in which a brass band of snowmen lead a ballroom dance. Lubitsch stuck with comedy for pretty much the entirety of his remaining career.

A little too smitten with her own glamorous image, Negri would soon founder in America, playing the role of the jaded “woman of the world” on and offscreen until audiences considered her something of a joke. One bad move was her exaggerated public histrionics at the 1926 funeral for Rudolph Valentino, with whom she claimed to have had a love affair. Weeping, wailing, fainting repeatedly, collapsing onto his casket as the camera bulbs flashed, she seemed to many to be staging a particularly tasteless PR stunt. Before his abrupt death from surgery complications at age 31, Valentino had had considerable troubles with bad publicity himself. Despite relaxed social mores in the Jazz Age, the blatant male eroticism he transmitted onscreen was ill-received by many defensive all-American he-men. He was subjected to a lot of public ridicule, which some foppish, preening role choices and various rumors (including those regarding wife Natacha Rambova’s purported bisexuality) only exacerbated.

Thus the screen’s “Great Lover” was already on the defensive in 1925, just four years after he’d exploded into stardom. The first feature in his new United Artists contract was The Eagle, a red-blooded adventure/romance in which he keeps his shirt on and wears no bejeweled jockstraps. He’s a young Cossack lieutenant in Russia’s Imperial Guard in the 18th century, whose bravery and horsemanship attract the attention of the middle-aged Czarina (Louise Dresser). But once he realizes she intends promoting him to her bed, he harrumphs “I enlisted for war service only” and scrams, a bounty soon put on his head as a “deserter.”

The story then veers into Scarlet Pimpernel territory, as our hero dons a masked alter ego to avenge his late father’s swindling by a fellow nobleman. He also pitches woo to that villain’s virtuous daughter played by Vilma Banky, who’d also co-star in Valentino’s next, final film, the hit sequel Son of the Sheik. Lesser-known Eagle is not among his best surviving vehicles, nor is it a career peak for director Clarence Brown, whose resume would encompass later classics like The Yearling, National Velvet, Intruder in the Dust and Idiot’s Delight, plus myriad glossy celluloid pedestals for Gable, Garbo, and Crawford. But it is good fun.

As stubbornly underappreciated as Valentino was overexposed, Anna May Wong trailblazed as the first Asian American actress to achieve prominence onscreen. Yet she was sorely frustrated by the stereotypical roles she was offered, as well as the fact that rare plum ethnic parts like the female lead in the 1936 film version of Pearl S. Buck’s China-set bestseller The Good Earth got cast with Caucasian performers in yellowface. Towards the end of the silent era she decided to try her luck in Europe, where her opportunities considerably improved.

Among the films she made there was Richard Eichberg’s 1929 Pavement Butterfly, a German-British coproduction shot in France. She plays a carnival dancer framed for the murder of her protector by a jealous coworker; fleeing, she ends up in the garret of a struggling artist (Louis Lerch, an appealing naturalistic actor.) Alas, her erstwhile tormentor keeps turning up to ruin her life anew. The melodramatic story feels cobbled together from other movies, particularly then-recent Janet Gaynor/Charles Farrell vehicles. But there are many pluses to this well-mounted effort, including some notably stylish touches, good location filming, and the beautifully photographed star nicely underplaying the purple emotions called for.

Also rising above a somewhat pulpy narrative is Victor Schertzinger’s Forgotten Faces from the prior year, a Paramount remake of a film eight years prior which they’d remake yet again eight years later—though those other versions are now lost. Clive Brook and an atypically scruffy William Powell play thieves who successfully rob a private casino, but barely escape its being raided by the police. It turns out that was a trap orchestrated by Olga Baclanova (even more detestable here than she would be later in Tod Browning’s infamous Freaks), the faithless, neglectful mother to Brooks’ beloved child. Years later, he manages to escape prison in order to keep this gorgon from tracking down the now-grown daughter (Mary Brian) he’d safely delivered to the doorstep of a benevolent wealthy couple. It’s a sort of proto-noir whose more improbable elements are easily sold by deft direction and very good leading performances.

Many of these films have only recently been restored, and were largely unavailable or thought lost for decades. One silent feature that’s never gone away, however, is the century-old Safety Last! It is not Harold Lloyd’s best vehicle, but it has the sequence with which he remains most identified: An extended (over 20 minutes) climax in which his hapless hero must scale a 12-story highrise by hand—a department-store publicity stunt he’s forced to take over from an acrobatic friend (Bill Strother) when the latter is chased away by a cop. It is arguably the most famous of all silent comedy setpieces, still an ingeniously staged and conceived wow… even if it was not really as hair-raising a piece of stunt work as Lloyd liked to claim. (After his death, it was revealed that the climb’s vertiginous heights were in fact cleverly faked.)

Lloyd is generally considered the most prosaic of the era’s comedic “big three,” lacking Chaplin’s poetry and Keaton’s deadpan genius. But his movies were, and are, great mainstream entertainment—Safety Last! tied for the No. 3 slot among 1923’s box office hits with Universal superproduction The Hunchback of Notre Dame, which had cost 10 times as much. (At the top of the heap was Cecil B. DeMille’s original Ten Commandments, followed by western epic The Covered Wagon, both fairly creaky relics now.) It’s still friskier and more fluid, not to mention funnier, than anything else on that list.

It was a milestone for the star in other ways, too, as during its production he married Mildred Davis, his leading lady here and in a dozen-odd prior vehicles. Though Lloyd’s stardom faded away in the sound era, he arguably had the smoothest ride of any silent-era luminary. Wise in business as well as art, his fortune survived talkies, the Depression, and all other travails, as did his marriage. He’d never surrendered his films’ rights to a studio, so when there was a first revival of interest in silent comedy greats around 1960, he himself assembled feature-length compilations of his work for new audiences.

Harold Lloyd’s signature character was the unpretentious little guy who made good—despite an occasional hilarious physical peril—realizing the classic American Dream just like the industrious actor-producer who played him. He was a go-getter who duly got it in real life.

As always with SF Silent Fest, all the programs above will feature live musical accompaniment by various organists and ensembles.

A DAY OF SILENTS runs Sat/2. Castro Theatre, SF. For tickets and more information go here.