When The New York Times decided to stop endorsing candidates in local races, I figured it was really about the money. Interviewing, researching, and writing that level of political opinion on that number of races requires a team of reporters and editors, and takes months. Cutting out the endorsement for Brooklyn borough president frees up those staffers to do other things (and allows, in the end, for a smaller editorial staff).

But that’s not what happened at the Los Angeles Times and The Washington Post. They already had endorsements ready for president of the United States, and at the last minute, the owners of the papers pulled the plug and said: No endorsements. In both cases, the papers would have endorsed Vice President Kamala Harris.

It’s pretty clear to me what went on.

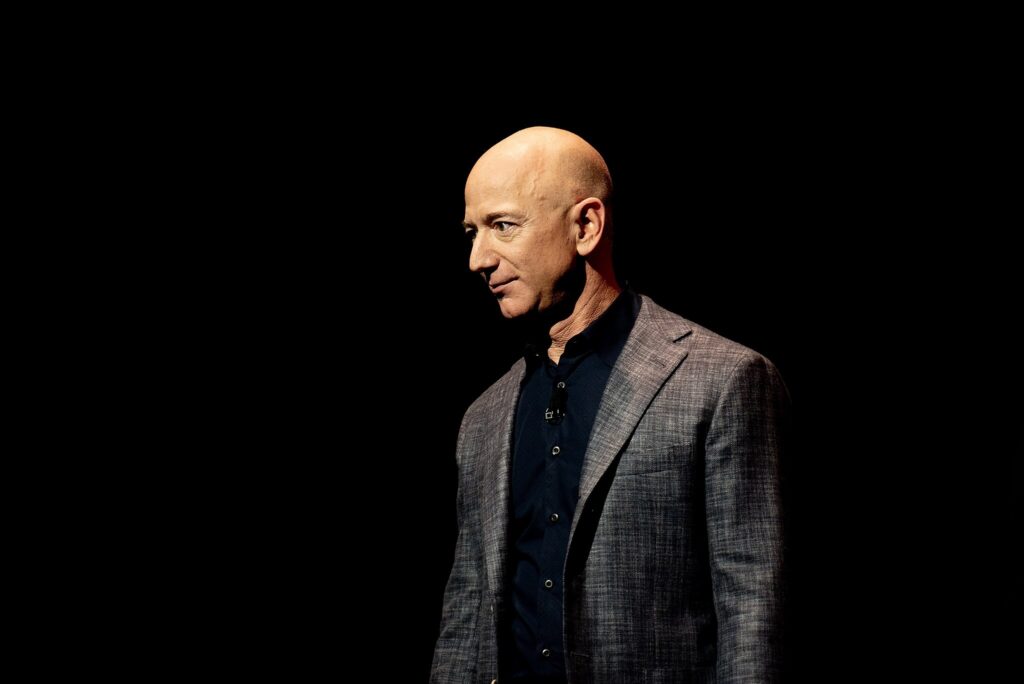

Jeff Bezos, who founded Amazon, owns The Post, and Patrick Soon-Shiong, who made a fortune in the pharmaceutical industry, owns the LA Times. Two billionaires with no background in the newspaper business—and with very clear personal interests in the outcome of the election.

For starters: Two billionaires. Trump has been very good to the rich, has cut their taxes, and has promised more tax cuts. But there’s more.

Soon-Shiong, Politico reported, sought a cabinet post in the Trump Administration. Bezos also runs Blue Horizon, a space company that is seeking federal contracts. The Daily Beast reports that a Post editor says a meeting between Bezos and Trump led to the paper pulling its endorsement of Harris.

I have had many, many disagreements with the NY Times over the years, but at least it’s controlled by a family with a long legacy in journalism. At least it’s safe to say that The Times wasn’t influenced by the possibility of retribution during a second Trump presidency.

This idea that billionaires can buy major newspapers as their own playthings and use them for their own financial gains outside of the industry is seriously disturbing. We just saw why.

The Board of Supes Land Use and Transportation Committee will consider Monday/28 a measure that changes the rules for the sale of below-market-rate condos. It’s an odd bill by Sup. Myrna Melgar, that the planning staff says would impact only a small number of buildings. As we reported, the measure:

would increase the selling price for some older units a level affordable to people making 130 percent of the Area Median Income (that’s two people with a combined income of $155,000) and increase the eligibility to people with up to 150 percent AMI ($179,850).

That might make some of the older units easier to sell—at a higher price.

The idea of BMR condos is that people can buy them, and get some equity—but they can’t be sold as speculative assets at maximum value. In one case, on Valencia Street, the planning staff notes:

The Valencia Street unit is an older BMR unit, and the current owners are the second owners. When these owners purchased the unit in 2018, the affordable price was calculated using a method MOHCD now finds is not reflective of current affordable pricing. MOHCD used the newer methodology in 2022 to calculate the new affordable price for the Valencia Street unit. This resulted in an affordable price approximately $60,000 less than the original purchase price. The proposed waiver allows MOHCD to reset the affordable price to the original purchase price, instead of relying on all the standard factors and assumptions to calculate the price. This is also meant to make the repricing process for eligible BMR units simpler and easier for staff and the public to understand. …

After the price is adjusted, the qualifying income is also adjusted to make sure that buyers have enough income to afford the new, higher price. This adjustment is limited to an increase of 20% of the qualifying income AMI, up to a maximum of 150%. If the qualifying income is not adjusted in conjunction with this price increase, future buyers would likely spend more than 33% of their household income on housing costs. This would make the unit inherently unaffordable moving forward. Therefore, the price adjustment also needs the corresponding qualifying income adjustment to make sure the unit is affordable to buyers in the future.

Sounds fair enough—except that, as housing activist Calvin Welch noted at the Planning Commission hearing on this, the developer of the market-rate property than includes BMR units was supposed to be responsible for keeping them affordable for the future.

As Welch noted in a memo to the Planning Commission:

At the center of Section 415 ( “Inclusion Affordable Housing Ordinance”) is the assumption that the “project sponsor”, that is the developer of the market rate development ( “the private sector”) subject to Section 415 has an ongoing responsibility to meet the income levels required by the ordinance “for the life of the project” (Section 415.8 (a) (4) ).

The Melgar proposal ignores that requirement and instead shifts the responsibility for future affordability to the general public by allowing a once affordable priced unit to be increased to levels that simply make it no longer affordable. By allowing AMI increases her ordinance does move the program away from meeting the needs of “low and moderate income households” as defined in our own Housing Element which defines affordability at far lower AMI levels.

The commissioners were a bit dubious of the plan, but still forwarded it to the supes on a 5-1 vote. The LUT hearing starts at 1:30pm.

Way back in 1983, Safeway announced it would close a store on Larkin and Bush. Shortly after the announcement, Sup. Nancy Walker introduced a bill that would have required community notice before a full-service grocery store closed. It passed the board, but Mayor Dianne Feinstein vetoed it, saying that the measure was “unnecessary intrusion of government regulatory authority.”

But now that Safeway is talking about closing its only Western Addition store, Sup. Dean Preston has brought the idea back. He’s introduced a bill that would mandate six months’ notice of a supermarket closure, so the city and the community can work to make sure that the shutdown doesn’t create a food desert.

That bill, cosponsored by Sups. Aaron Peskin and Connie Chan, comes before the full board Tuesday/29. Since Mayor London Breed has taken credit for convincing Safeway to delay the closure, it’s hard to see how she could veto it—except that she doesn’t want to support anything that gives Preston a victory.

After a scandalous process, the San Francisco School District has put a hold on closing schools. But the district hasn’t said that closures are off the table, and there’s no timeline for that discussion.

The Board of Supes will hold a hearing as a Committee of the Whole Tuesday/29 to discuss

the state of educators, para-educators, administrators, and school staff impacted by San Francisco Unified School District’s (SFUSD) recent announcement of potential school mergers and closures; and requesting the SFUSD Superintendent to report.

Might be good to hear from some School Board members and candidates too; this is probably the biggest issue that worries parents and could drive them away from the public schools, and it’s largely missing in the election debate.