You can raise unlimited money to run for DCCC then use that for another campaign — say, for supervisor

By Tim Redmond

FEBRUARY 4, 2015 — You want to raise political money, fast, in big chunks, in San Francisco? It won’t be through a campaign for supervisor, or even for mayor: Local laws limit individual donations to those races to $500.

But file for the somewhat obscure office of Democratic County Central Committee, and you can raise all you want, wherever you want, with essentially no legal limits.

And once you’ve raised that unlimited money, you don’t have to spend it on the DCCC race – it can go for all sorts of other things.

Including, apparently, a race for supervisor.

Campaign documents reviewed by 48hills show not only big special interest contributions to supervisor candidates’ DCCC campaigns – Scott Wiener, for example, got $10,000 from the San Francisco Apartment Association and Malia Cohen got $7,000 from Ron Conway – but reveal some curious transfers that at the very least raise questions about how local money is raised and spent.

In 2012, Cohen ran for DCCC and collected $116,700. That’s a lot of cash for an office that sets policy for the local Democratic Party. But DCCC campaigns raise name recognition for candidates, and Cohen spent $39,588 campaigning for the office.

The remainder of her DCCC money was spent after the race.

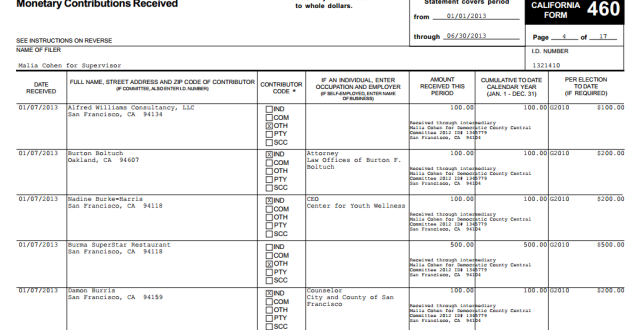

Among the disposition of that money: On Jan. 7, 2013, documents on file with the Ethics Commission show, Cohen transferred $10,000 from her DCCC account to the Malia Cohen for Supervisor campaign.

Now: The Cohen for Supervisor campaign can’t take $10,000 from anyone, even Cohen’s other campaign committee. The limit by law is $500.

So the supervisorial campaign listed 31 individual donations, from $100 to $500, and stated that they were “received through intermediary Malia Cohen for DCCC.”

In other words, that $10,000 was repurposed – from one campaign that can raise unlimited money to another that is under strict contribution limits.

I have left numerous messages for Cohen, who acted as her own campaign treasurer, and she hasn’t answered my question: Did all of those donors agree to move their money from one campaign to another?

Legally, it turns out, they don’t have to. Campaign finance experts I’ve spoken to say that as long as the total contributed by any one individual to the Malia Cohen for Supervisor campaign doesn’t exceed $500, what Cohen did is perfectly legit.

According to a Dec. 11, 2002 advice letter from the Ethics Commission, it’s legit to transfer money from one campaign to another, but:

[I]n order to comply with local contribution limits candidates must attribute to particular contributors funds transferred from one campaign account for City elective office to another of that same candidate’s campaign account for City elective office.

-

To determine whose funds have been transferred, the Ethics Commission will use the same attribution procedures adopted by the Fair Political Practices Commission, which require a candidate to use either “last in, first out” or “first in, first out” accounting methods.

-

Both candidates and contributors are responsible for complying with local contribution limits.

Here’s the relevant Ethics Commission regulation:

“Regulation 1.122-2 Transfer of Funds in a Candidate’s Campaign Account.

(a) The use and transfer of funds held in a candidate’s campaign account during an election, after the candidate’s withdrawal or when such funds become surplus, are regulated by both state and local law. Candidates and treasurers must comply with both state and local law in the handling of such funds. Under some circumstances such as when funds become surplus, state law prohibits the transfer of funds.

(b) A candidate who transfers funds from one candidate campaign account to another must file Form SFEC-122 to disclose whether “last in, first out” or “first in, first out” was used and information regarding the contributions that were transferred.”

In other words, Cohen should have taken the money from the contributors who had most recently given her money. It’s impossible to tell from campaign records whether that happened, since many of her contributions came in on the same days.

If there is an SFEC Form 122 on file for her DCCC of 2014 Supervisorial campaign, I can’t find it in the Ethics database.

Of course, once money’s in the bank, it’s all fungible: Was it those 31 individuals who actually shifted their donations to Cohen for Supervisor, or was it Ron Conway? If Conway hadn’t forked over $7,000, would Cohen be flush enough to move $10,000 in other donations to her supervisorial campaign? In the end, it’s all the same money flow.

Which is why critics say the DCCC loophole is a serious problem.

Jon Golinger, who ran the No Wall on the Waterfront campaign, told me that “While the Koch brothers and corporate donors may be using Citizens United to make a joke out of our national campaign finance laws, San Francisco voters have repeatedly made clear they’re serious about strictly limiting campaign contributions to local elected officials to $500 to stop political corruption and undue influence.

“That’s why it makes a mockery of what San Franciscans voted for not to close the unlimited donation loophole that some city elected officials have exploited to accept a $10,000 donation check with one hand when it would be illegal for them to take any more than $500 with the other hand.”

The city has every right to limit the individual donations to local campaigns. But thanks to a Republican bill that got through both houses of the Legislature in 2012 makes it impossible for local government to control contributions to partisan county committees.

The measure, by the GOP’s Chris Norby, is now enshrined in state law:

- (a) Nothing in this act shall nullify contribution

limitations or prohibitions of any local jurisdiction that apply to

elections for local elective office, except that these limitations

and prohibitions may not conflict with Section 85312. However, a

local jurisdiction shall not impose any contribution limitations or

prohibitions on an elected member of, or a candidate for election to,

a county central committee of a qualified political party, or on a

committee primarily formed to support or oppose a person seeking

election to a county central committee of a qualified political

party.

So unless that state law gets changed, county committee races will remain potential slush funds for candidates for other offices.

In 2012, for example, records show that the five members of the Board of Supervisors who were running for DCCC – David Campos, David Chiu, Eric Mar, Cohen, and Wiener – raised a total of $388,831 for that office. Almost half of that — $170,650 – was spent by those candidates after they had already won the DCCC election.

A total of 120 donors gave more than $500, the limit for a local race.

There are very few limits on what a candidate for DCCC can do with his or her money after the race is over. It can’t go for personal expenditures, of course, but it can clearly be used for polling, staff, and other work that is related to other campaigns (say, for supervisor).

The big donors know how the game is played. You want to help Wiener get elected supervisor? A cool ten grand to his DCCC campaign will allow him to print signs with his name on them, pay for slate cards with his name on them, and in general get his name out.

Wiener has been on the DCCC for years, and is a past chair. It’s inconceivable that he could lose a race for re-election to that body, where name recognition is a key element. He could spend $1.00 and win.

But the landlords can’t give $10,000 to his campaign for supervisor, any more than Ron Conway can give $7,000 to Cohen’s supervisorial effort. So they use the DCCC.

Campos raised $121,753 for his DCCC race, including several contributions of $5,000 or more, and that clearly helped his campaign for state Assembly. Those donations, however, could have gone directly to his Assembly race, where the limits are much higher. Same for David Chiu, who raised just $24,414, with several contributions higher than the local limit (but well within the state limit for Assembly races).

Wiener, like Campos, had no serious opposition in his re-election campaign for supervisor, and he’s been effectively running for state Senate for several years. So the extra promotion his DCCC money gets will wind up helping the (officially undeclared) Wiener for Senate race.

And Cohen? She was running for supervisor. Under $500 contribution limits. And this, while perfectly legal, sure looks a little funky to me.