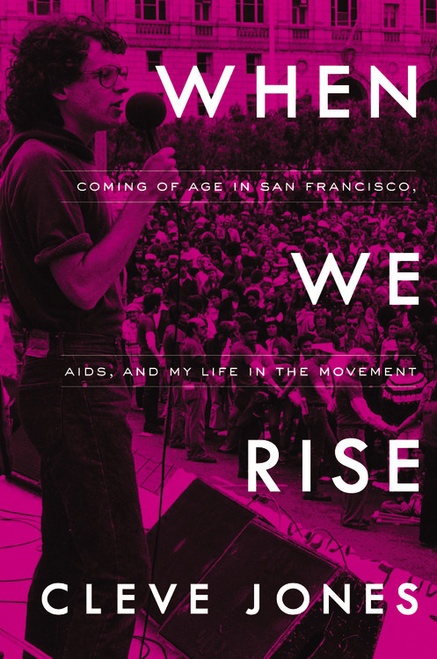

The arc of the public gay rights movement’s history is not very long at all. It’s just about the length of one full life, and while Cleve Jones may be slightly too young to encompass it all, he managed to be at the center of most of its epochal events. In his new autobiography, When We Rise — the basis of an ABC miniseries penned by Dustin Lance Black and released in February — we finally get to take in the scope of that life. (See Jones speak Fri/9, 7pm at JCCSF.)

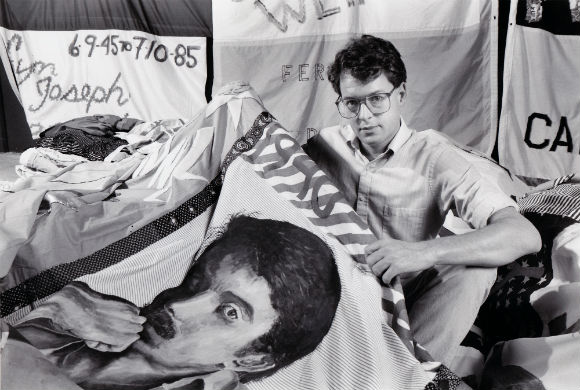

No, he wasn’t at Stonewall, although he was engaged in non-gay anti-war and civil rights actions from an early age. But from the San Francisco bathhouse heyday of the early 1970s (including request stops at the Stud bar), through his political apprenticeship to Harvey Milk (Jones was among the first to see his body after he was shot), his co-founding of the San Francisco AIDS Foundation in 1983 and his conception of the NAMES Project AIDS Memorial Quilt in 1985 at the onset of the AIDS era, his work against Prop 8, his portrayal in Milk, and now his work on with UNITE HERE to expand labor protections for LGBTQ workers…. well, Jones has been there a lot, and reading about his life necessarily fills in a lot of details about the history of the gay rights movement.

(One example: During the height of the AIDS epidemic, the Quilt provided a much-needed yin to Act-Up’s essential yang: “While the fury of ACT-Up was justified and powerful,” Jones writes, “we needed more than rage to survive this plague. We needed love. And everywhere the Quilt traveled, we found love.” One of the dishiest tidbits in the book is when ACT-UP founder Larry Kramer, raging at the Quilt’s political passiveness, calls for the Quilt to be burned, and Jones responds, “OK, but can we wrap you in it first?”)

Now, with the release of the book and the miniseries, we’ll see how he fits into and influences another era: the Trump presidency. I spoke with the 62-year-old Jones over the phone about his life and what’s next for the LGBT movement.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6CBZZgXaE_A

48 Hills You were very close to Harvey Milk, and you spoke a couple weeks ago at the candlelight vigil for Harvey Milk in the Castro. Your speech moved a lot of people, especially coming right after the election of Trump.

CLEVE JONES There’s just been so many times in my own life when I felt that it was over. And I think that for queer and trans people this is a very frightening time, and I just want to remind people that we’ve faced life-threatening challenges before. That’s also the theme of my book, which was that the movement saved my life. I think people need to prepare themselves, and be very strong and very strategic, and know that we can still win.

48H You also led the march after the Pulse Orlando massacre that united the queer and Latino communities here. It’s been quite a year of tragedy, along with hope, for queer people, and especially queer people of color. It’s quite a turn from the accomplishment of, say, same-sex marriage. I wonder where you think we are now with GLBT politics?

JONES A couple thoughts. First of all, in my lifetime, I have seen extraordinary change. Change is possible; the lives of LGBT people have been profoundly transformed over the course of the last half century. However, these election results clearly show us that everything we’ve achieved true can be swept away in the blink of an eye. Unfortunately history gives us far too many examples of when that has happened.

I would also say that the LGBT political movement and the larger progressive movements, in my view, have been weakened by some of the more extreme manifestations of identity politics. I think that we need to work together. So one message that I’ve been repeating over and over is that, if we allow our capacity for empathy to be limited by skin color, or heritage, or gender, or generation, then I think we’re really in trouble. Now, more than ever, people need to unite, and respect each other, and have each others’ backs. We cannot afford to be divided.

48H Turning toward the book, you offer such a vivid rendering of what it was like to discover your sexuality — you came of age in Arizona via Pennsylvania, in a well-educated, middle-class Quaker family — when gay visibility was so hard to come by. It’s become cliche to say things like, “Oh you don’t know how hard to was to connect with other gay people before the Internet,” but you really nail it. One fascinating detail was how you were so involved in the anti-war in Arizona, but had no idea there was also a gay rights movement also happening. You were almost marooned until you spotted a legendary magazine article …

JONES It was Life Magazine Year in Review 1971, an article about gay men in San Francisco.

I had originally imagined this book being two equal parts. Part one would have been 1954-1981 and the beginning of the AIDS epidemic, and the second half would be 1981 forward. But when I started writing, I found it exciting to remember and relive those days. So many of my generation did not survive, so our collective knowledge and maybe some wisdom is being lost. So I spent a lot of time on that era of discovering myself and the early part of the movement.

For me, finding that magazine was a revelation. I had finally come to understand what the words meant, what I was being called — homo, etc — I had looked it up in some of my fathers’ textbooks, he was a psychology professor. So as soon as I discovered what I was, I learned that I was a criminal and that I was considered to be mentally ill. A pretty horrifying message for a 12-year-old to receive. But finding this magazine that spoke of a homosexual rights movement in San Francisco was a revelation to me — it kind of brought both sides, my sexuality and my activist side together. And I immediately vowed to move to San Francisco.

48H Moving ahead to that AIDS era — was that the hardest part to write?

JONES You know, once I started writing about that time, I started getting so deep into it that before I knew it I felt like I was writing a history of the pandemic, which is not what I set out to do. So the fact that writing about it was so painful that I was essential deflecting — and honestly, I had written about it already in my earlier book Stitching a Revolution: The Making of an Activist — I think that almost made me move pretty quickly through those year. It’s still very painful.

But the chapter that was hardest for me to write, and hardest for me to read aloud, was the chapter about November 27, 1978, the day Harvey Milk was assassinated. And that really surprised me, that after four decades it would still be so wrenching. The horrible sense that everything was over came rushing back through me. At that point I was still estranged from my father, and Harvey was a father figure, a mentor, a real leader. And to see his body there, and the blood everywhere, I kept thinking, “It’s over, it’s over, it’s over.” But the night after he was shot, which thousands of people marched to City Hall with candles, I knew it wasn’t over, it was just beginning. So that has stayed with me my whole life. You don’t give up.

48H One bright thread in the book runs from your experience as a youth with the Quakers, and how their embrace of nonviolence was very formative for you, through your conception of the AIDS Quilt, which stemmed partially from your knowledge of Quaker crafts and came to you during another memorial candlelight vigil for Harvey, in 1985. This thread, and others like it, adds a real structure to the narrative, besides just a chronological retelling of your life. Did you sit down and deliberately plan out the book’s structure before you wrote it?

JONES Oh, I’m a horrible procrastinator. Every writer I know said you’ve got to sit down a few hours every day and write something, and build an outline, and all this. Well with me all that went right out the window. I pretty much poured this book out in 10 days of marathon sessions, right on deadline. Some of it was with Dustin Lance Black at a dining room table in LA.

48H Which brings us to the miniseries. What are some of the emotions and feelings you have of your life being the basis of a major network’s miniseries? You’ve already been portrayed by Emile Hirsch in Milk, and now you’ll be a central character played by Guy Pearce in When We Rise. Millions of people will know your life and work…

JONES Well, I don’t know quite what to expect, because I haven’t seen it yet! I was very happy with the way the film Milk turned out, and so many people who are involved in this miniseries were involved in that. It’s just a surreal experience. I’ve been through this already, and it’s just as weird as could be.

With Emile Hirsch in Milk I got really lucky. I’ll tell you a funny story. He flew in to meet me before filming. I still had my little pickup truck then, and so I drove him around town, showing him some of the important places in my life. At one point, we were on Divisadero heading back towards Castro, and I suddenly realized I was trying to “butch it up”! When I caught myself doing that, I was just appalled. I was just like, really? Ha. What was I doing?

So I took him back to my apartment, and made him spaghetti, and told him, Look, I’m a queen. But I don’t want to be a cardboard stereotype. And I think Emile did a fantastic job. So I’m hopeful that Austin McKenzie, who plays the young me, and Guy Pearce who plays the mature version, I can just hope they got it right, too.

48H So beyond anticipating all this attention, what’s next for you?

JONES I anticipate that I’ll spend the rest of my life working with the labor movement to try to fight back against what happened in this last election. i work for UNITE HERE which is the hospitality workers union, which is mostly immigrants working on hotels, casinos, restaurants across the United States, food service workers, some laundry.

So this is a very vulnerable population, and I feel that the aggressive weakening of labor movement really paved the way for the rise of Trump. I’m really grateful to be involved with the labor movement, and I want to help keep it open to LGBT people.

There’s a lot of work for us all left to do. And I really hope this book and the miniseries will inspire people who hear these stories to think about what they can be doing, how their lives can become part of this broader social movement for peace and justice. We need people to make that commitment now more than ever.

CLEVE JONES

in conversation with Peter Stein

Fri/9, 7pm, $28-$38.

JCCSF

Tickets and more info here