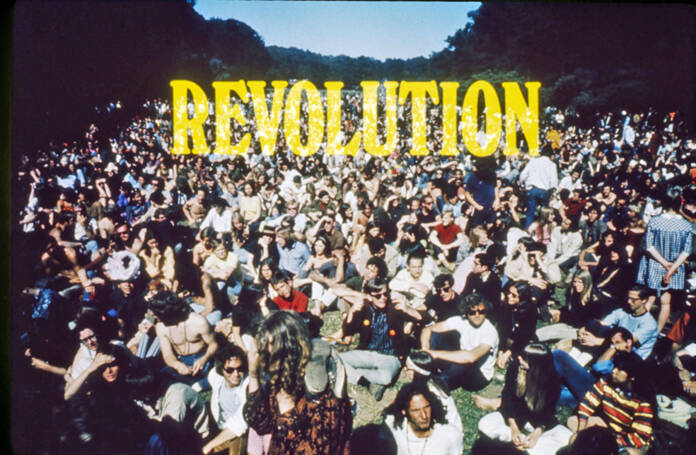

At this point even six months ago may feel like an entirely different, long-lost epoch—as, meanwhile, November 3 can’t possibly come soon enough. But if you really want to take the Way-Back Machine for a spin, climb aboard the 1968 documentary Revolution, which Jack O’Connell shot during San Francisco’s fabled Summer of Love and released the following spring. A WWII Army veteran who subsequently worked in advertising on Madison Avenue, he entered filmmaking by apprenticing in Italy under two great directors on two of their greatest works: Antonioni’s L’avventura and Fellini’s La Dolce Vita.

O’Connell died almost exactly a year ago at age 96. His passing was little-noted, perhaps because his screen career was so brief, purportedly curtailed by neurological damage he suffered from an assault. But his own few directorial credits provide a remarkable Rorschach of counterculture movements, aesthetics, and popularizations in the heady years between 1963-1971. Revolution itself is probably the best feature (either nonfiction or dramatic) about San Francisco as flower power nexus, as it’s both enthusiastic and clear-eyed, non-exploitative yet fun. No doubt it prompted yea more busloads of wayward youth to land in the Haight-Ashbury, where the scene would degenerate from overcrowding, drugs and crime for years to come as a result.

O’Connell and crew aren’t blind to the downsides already present in 1967, with STDs and freakouts necessitating the foundation of the neighborhood’s Free Clinic, while hordes of touristic looky-loos threaten to outnumber the “freaks” they’re snapping photos of. The movie glimpses greater San Francisco by giving a little time to viewpoints of the police, average citizens, and socialites, all of whom seem more amused than appalled by the circus that’s come to town. There are brief interviews with Herb Caen, Rev. Cecil Williams, and the Mime Troupe’s R.G. Davis. There’s a nude dance under psychedelic lights by the troupe of Anna Halprin, who is still kickin’ at 100; plus concert footage with Quicksilver Messenger Service, Country Joe & the Fish, Steve Miller Band, and Mother Earth.

But mostly Revolution just samples the lysergically-saturated local color, with one actual tripping sequence (witness the incredible wowness of several people sitting in a room, feeling fruit and petting a cat!), but more often, you know, just being. Our exemplar of the “new freedoms” is supposed to be a young woman who’s renamed herself Today Malone. A sometime past actress and model turned occasional street hawker of the Berkeley Barb, she is pretty, and pretty vacuous. But at this moment in time, her going with the flow has a questing, innocent optimism; cynicism and predation haven’t quite hit the Haight as yet.

Revolution is skeptical at times, but also seduced by what it’s depicting, and O’Connell depicts it with an irresistible eye for the charming or beautiful detail. Almost twenty years later he’d reissue the film as The Hippie Revolution, a title change demanded by producers of the notorious 1985 Al Pacino costume-drama flop also called Revolution. Material added then revealed, among other things, what happened to Today—namely, two kids, single motherhood, gainful employment, and a whole lot of sobering reality. (You can see this version of the film here.)

The director’s other films were all narrative features. His debut, 1963’s B&W Greenwich Village Story, was a drama whose cast included fellow future directors James Frawley (The Muppet Movie) and John G. Avildsen (the original Rocky & Karate Kid). It depicts a jaded and exhausted Manhattan hipster scene well in need of being washed away by the next counterculture wave. Its cafe denizens are all middle class post-collegiate kids playing folk music, improvising pseudo-Ginsbergian poetry, looking miserable at parties, etc.

The hero (Robert Hogan) is your classic tortured artiste, stewing in a pit of angst (his never-finished novel is called Get Ready to Crawl), while dancer girlfriend (Melinda Cordell) wishes he’d get his shit together. He can’t, or won’t—which leaves her at the mercy of a back-alley abortionist. Dismissed at the time by The Village Voice’s Andrew Sarris as dated boho hokum, Greenwich Village Story now looks more of a mixed bag, alternately embracing cliches and transcending them. It can’t always be taken seriously, but unlike similarly-themed movies of the era, it’s hardly exploitative sleaze.

Revolution was a particular success in Denmark, so O’Connell went there in 1969, and was very much taken with its societal smoother embrace of new freedoms, particularly in the realm of sexual mores. He resolved to provide the definitive portrait of the liberated New Woman there. That finally resulted in 1971’s Christa, whose Copenhagen heroine (Birte Tove) is a platinum-blonde, miniskirted, go-go-booted air hostess who frequently jumps into bed with her 1st Class passengers. (After landing, that is.)

They are agog, and perhaps a little scared, by how “free” she is, particularly as she seldom misses an opportunity to shed clothes.

But Christa is no cartoon “nymphomaniac,” just a woman without hangups (“Morality was invented by you men to control the sexuality of women,” she tells one flabbergasted Italian), and she is notably more emotionally mature than nearly all the guys she meets. She’s really just auditioning them to see who’s man enough not just for her, but her toddler son—whose stalker-ish father she’s spurned for very good reasons.

Though viewed as a dated outsider’s fantasy in Scandinavia by the time it premiered (O’Connell labored on the film so long, his original cut ran four hours), the movie played differently elsewhere, even under the geographically bogus US title Swedish Fly Girls. It did, and still does, work as a sexual revolution empowerment fable, complete with chic mod fashions and a Manfred Mann-produced soundtrack whose songs predate Superfly in frequently commenting on the action. (Albeit in a vague way, as one chorus advises us “Come get strung out on the Groovy People Show!”). Once again, O’Connell made a movie that cannily reflected its time without resorting to pat exploitation.

Alas, he only made one more movie, a stageplay adaptation variously called City Women and Up the Girls that sounds like it furthered his interest in women and the politics of “liberation.” But after being shown at the 1975 Cannes market, the movie (in which O’Connell actually played the male lead) couldn’t find distribution, and appears to have never been seen since. It’s the only film of his that is not offered free for viewing on the aforementioned website.

While Revolution may satisfy the urge for a nostalgic flashback. there are plenty of new documentaries coming out this week, both glancing backward at other cultural phenomena and taking a hard look at some ongoing political realities. The two are combined in Kentucky African-American drum corps portrait River City Drumbeat. (See our interview with the filmmaker here.) It opens Friday at the Roxie and Rafael’s virtual cinemas.

Also arriving at those same online venues (plus BAMPFA) is A Thousand Cuts, Ramona S. Diaz’s harrowing portrait of the social-media propaganda, free press suppression, and police violence running amuck under populist Philippines President Rodrigo Duterte; and Scott Crawford’s Creem: America’s Only Rock ’n’ Roll Magazine, a suitably raucous history of the beloved 70s rock rag.

At the Roxie alone, there’s Sunless Shadows, in which Mehrdad Oskouei trains his camera on women at an women’s incarceration center, many of them (including several teenage girls) there for murder—seemingly the only way they could end domestic abuse from violent husbands and/or fathers.

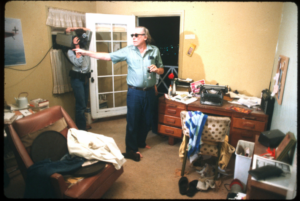

‘You Never Had It: An Evening With Charles Bukowski’

For a contrastingly ultra-masculine, even old-school-sexist POV, there’s You Never Had It: An Evening With Charles Bukowski, which is comprised of Italian journalist Silvia Bizio’s previously-unseen long, boozy 1981 chat with the late writer. It’s for completists only—much as I love Bukowski, you can tell even he realizes he has nothing much of interest left to say here. It’s accessible through CinemaSF and the Rafael’s virtual programs as of Fri/7.

Available on VOD and DVD this Tuesday is Tim Slade’s The Destruction of Memory, which charts the rise of deliberately targeting cultural-heritage sites as a weapon of war–and means of erasing ethnic or religious groups’ entire historical identities—within the last hundred years. From Nazi arson of Jewish landmarks to the bombing of Sarajevo’s National Library and the Iraqi Museum’s looting, these acts remain frustratingly under-defined and under-punished by the relevant international human rights bodies. (More info here.)

Last but not least, there’s the stranger-than-fiction story told in Gabe Polsky’s Red Penguins. This culture clash comedy—with hair-raising guest appearances by the Russian mafia—portrays the real-life attempt to pour American investment money into Russia’s fabled Red Army hockey team after the Soviet Union’s collapse. It was a commercial enterprise doomed to failure amidst economic chaos and infinite corruption, but it provided some whopping anecdotes (ice-skating strippers in the halftime show, anyone?) before it ran its course. The documentary is available as of Tue/4 on various streaming platforms (More info here.)