UPDATE: After press stories and communication from local officials, Bank of America removed the signs warning against memorials. State Senator Scott Wiener told us, “I spoke with senior Bank of America folks yesterday about the incredible importance of this sacred site to our community. They have agreed to remove the signs. Previously, the bank manager would take care of the area and store memorials that had been up for a while until someone could claim them. This branch has been closed for months, however, so there was no one to monitor the site, and Bank of America was concerned after political and other signs were pasted to the building itself and covered the windows. However, B of A immediately acknowledged the importance of the site to the community and agreed that it was of the utmost importance that people be able to post memorials on the small fence as usual. The bank branch will be putting up different signs eventually that will discourage people from posting things other than in that area, which they are reserving for the community. We are working on activating community groups to take over the maintenance.”

Bank of America spokesperson Colleen Haggerty sent us the following statement: “After speaking with community members, we realized the code enforcement signs created confusion and therefore we had them removed immediately. We absolutely understand the significance and importance of the space and will continue working with the community to ensure it remains a memorial, as it has for decades.”

Meanwhile, historian Gerard Koskovich added context to the importance of Hibernia Beach: “The angled corner of the building at the intersection of Castro and 18th streets has been a profoundly marked territory for expressions of shared queer public mourning since the darkest years of the AIDS crisis in the mid-1980s—well before Bank of America leased the space. Spontaneous folk memorials mounted in this location have commemorated the deaths of hundreds of members of the LGBTQ community, as well as famous allies such as Princess Diana in 1997. They also have marked our participation in moments of national mourning, including the death of Matthew Shepard in 1998 and the response to the attacks of Sept. 11, 2001. The GLBT Historical Society has preserved the Matthew Shepard and Princess Diana memorials, which can be accessed for research purposes.”

ORIGINAL STORY:

For decades at the southeast corner of Castro and 18th Street, makeshift memorials have commemorated recently passed members of the LGBTQ community. The stretch of pavement, a long-ago sunbathing and cruising spot known as Hibernia Beach after the adjacent Hibernia Bank branch, now a Bank of America, has served as a place to gather and grieve, as photo montages and personal items of the deceased are displayed along the little fence bordering the bank. During the AIDS pandemic and horrific events like the Pulse Nightclub massacre and Ghost Ship fire, these memorials provided solace and remembrance.

“That is our sacred ground, soaked in the blood of our ancestors and family,” former Assemblymember and Supervisor Tom Ammiano told us. “That was where we remember our dead, especially in times when their own families refused to even acknowledge their existence. It is a place of profound importance to the community.”

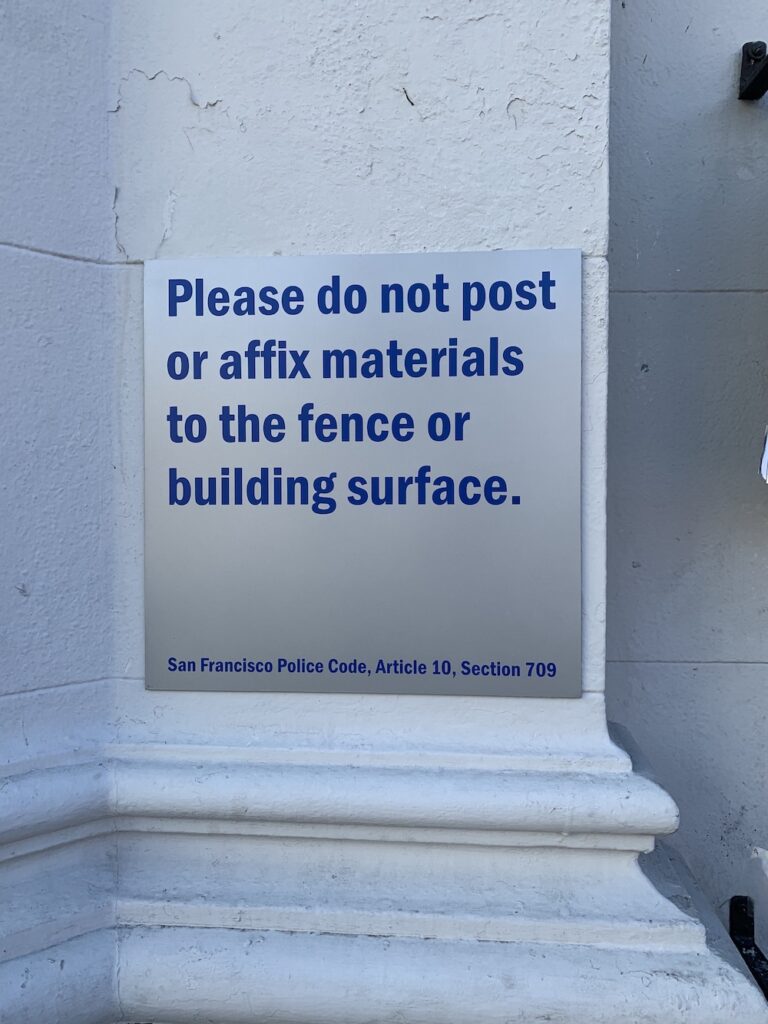

That sacred ground appears under threat, as new signs posted by Bank of America along the building warned, “Please do not post or affix materials to the fence or building surface.” The signs cite San Francisco Police Code article 10, section 709, which prohibits posting signs on private property without the owner’s consent, and states that violators can be “fined not less than $50 nor more than $500.” While a handful of memorials still stay up on the fence for now, the possibility of future such shrines could be in doubt.

Anger and confusion quickly spread online at the news. The signs were posted with no warning to the community, and seemed to many to ignore the magnitude of longtime cultural traditions. In an email to 48 Hills, Bank of America spokesperson Colleen Haggertty wrote

As a longtime business located at this historic location, we recognize the importance for people to honor this history and continue to temporarily preserve mementos placed onsite until regularly removing items for public safety and cleanliness needs.

In recent months, the increased volume of items placed onsite in addition to being posted onto our walls and windows began to pose greater potential safety concerns. The signage recently placed is to help curtail safety risks for neighbors and visitors. We remain committed to the Castro and are working with community organizations to find a solution that continues to allow mementos honoring the LGBT historical significance of this location while maintaining safety and appearance, especially once the newly renovated financial center reopens for business in March.

Supervisor Rafael Mandelman told 48 Hills that the move by Bank of America “absolutely” threatens sacred space. “It’s outrageous,” he said. “We were given no warning of the signs going up. I spoke with the property manager, and apparently there is a history of the bank being frustrated by maintenance burdens associated with the space. But this is not the solution to that problem.

“I told them the signs must come down,” Mandelman said. “And we should find a different answer, probably by bringing the Castro Community Benefits District, the Castro Cultural District, and the Castro Merchants together and finding away for them to take greater responsibility in the area’s maintenance. We remain in communication with the bank and are working towards that now.”

Bank of America’s signs come at an especially raw and painful time for the community. Like most other marginalized groups, LGBTQ people have been touched deeply by death, COVID-related and otherwise, in the midst of a depression-spurring pandemic, skyrocketing overdose rates, and healthcare crisis. Formal memorial services are being delayed, and it seems like everyone is going through an intense and extended personal grieving. Perhaps the uptick in volume of materials placed at Hibernia Beach is due to the exponentially increased need to mourn publicly.

The most recent huge loss for the community was Black LGBTQ and HIV activist giant Ken Jones, a veteran who was the first African American chair of SF Pride and a member of the BART Citizens Review Board after the killing of Oscar Grant. He passed this week of cancer, and many discovered the new signs while planning a memorial. Before this death, Jones recalled the importance of Hibernia Beach. “In the 1970s before the Internet, ironing board tables at Hibernia Beach were our community organizing headquarters,” Jones wrote in a memoir cited by the Bay Area Reporter.

Fellow activist Cleve Jones echoed the importance of the location, “This has been a tradition for many decades, a place where we came together to mark the passing of people who mattered to us. It’s where we remembers the victims of the Pulse massacre. It was a place to remember everyone, from our favorite bartenders to the most famous celebrities among us. For anyone to even think about taking that away is a grievous insult and must be reconsidered.”

Ammiano shared a funny memory of the Hibernia Beach area in the 1970s. “Every Friday, the line outside the bank would stretch down the block. We all wanted to cash our paychecks and go out drinking. This was during the time of the Symbionese Liberation Army, when Patty Hearst held up a Hibernia Bank branch. Well, we were all waiting in this humongous line and one queen yelled, ‘Patty Hearst didn’t have to wait!’ The whole place burst into hysterics.”

Ammiano’s mood turned dark at the thought of losing the space. “This is non-negotiable. We will protest, we will organize, I will pull out some nellie ninja shit. Nobody takes that space away from us. Nobody.”