I really, really didn’t want to talk about San Fransicko, the book that the right wingosphere has used to attack progressive policies in SF and other cities.

It’s mostly just silly stuff, and I figured it would be better if I just ignored it.

But then my old friend Jon Weber, who is now running the SF Standard, asked me to write a piece for a point-counterpoint about it. And I can’t turn down Jon, and I knew if they were going to be covering this, someone had to tell the truth, so I said yes.

And the more I thought about it, the more I realized we have to take this shit on, because all over the country, and increasingly all over the world, we are seeing San Francisco pilloried for its “leftist” policies.

The shitstorm is threatening to take down a progressive district attorney. Based on a recent poll, some group is trying to use the narrative to attack a progressive candidate for state Assembly.

It’s not going to end unless we challenge it. So I took a shot.

A version of this piece ran in the SF Standard here. Jon asked for 1,200 words, and I struggled to keep it to that length. But there’s a lot more to say, so let me expound.

To wit:

There is so much wrong with San Fransicko that I don’t know where to start, so I’ll just begin with the subtitle: “Why progressives ruin cities.”

That phrase alone shows how disgracefully little Berkeley writer Michael Shellenberger knows about the politics of the city that he so gleefully (and often with factual inaccuracy) attacks. It assumes that progressives have actually been running San Francisco.

San Francisco is run by a strong mayor, who controls the budget, appoints department heads and the majority of every major commission, and can unilaterally fill any vacancy in any elected office. The City Charter specifically bans the legislative body from “interfering” with city departments, giving the mayor the power to implement laws (or refuse to implement them) without meaningful legislative oversight.

The city’s chief executive runs the city. And there has not been a mayor of San Francisco who could remotely be called “progressive” in at least 30 years.

So the idea that “progressives” have created the problems on the streets of this city is simply, utterly, fundamentally wrong.

The homeless crisis that’s the focus of much of Shellenberger’s screed began in the early 1980s, when the mayor was Dianne Feinstein, who might as well be a Republican. She was succeeded by Art Agnos, who was in many ways a progressive, but lasted only four years.

Agnos had to deal with a recession and a budget crisis, and took the position that social services could address a problem that was really about affordable housing.

Then we had former Police Chief Frank Jordan, who was all about sweeps and clearing the streets; political fixer Willie Brown, who once said that homelessness was a problem that can’t be solved; corporate Democrat Gavin Newsom, who built his career attacking homeless people; tech-industry lover Ed Lee, whose policies created massive displacement, and now London Breed, who is at best a moderate.

“Progressive” actually has a meaning. It refers to a political philosophy that includes social justice, racial justice, climate justice—and economic justice. Progressives believe in using the tools of government, including taxes and spending, to fight economic inequality.

Some mayors of San Francisco have taken very progressive social stands; Newsom showed immense courage in legalizing same-sex marriage. But on economic policies—the policies that could really impact the crisis on the streets—the people who have run this city for decades have been mostly neoliberals. Our mayors have operated under the politics of Bill Clinton, not Bernie Sanders.

I would agree that many of their policies have made economic inequality in San Francisco—and its manifestation in evictions, homelessness, drug addiction, and social misery—worse. But that’s not the fault of progressives. We have been fighting with every bit of our energy to do things differently.

Every political leader in San Francisco ought to take what I call the Hippocratic Oath of Housing: First, do no harm. Housing in many major US cities is a crisis. Mayors ought to try to make things better—but you can’t do that if you are, as a matter of policy, constantly making things worse.

For decades, starting with Feinstein, the city approved millions of square feet of new office space. The recession slowed things down under Agnos and Jordan, but Brown cut deals with developers to build even more (including new office space in residential neighborhoods in the Mission).

Under Ed Lee, the city offered tax breaks to encourage tech companies to flood in. All of this brought tens of thousands of new high-paid workers—in finance, insurance, and real-estate under Feinstein and her successors, in tech under Lee—to the city.

New workers could pay more than existing residents. Without proper protections, existing residents were forced out, some of them onto the streets.

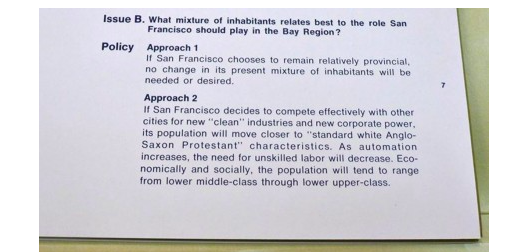

The jobs that the city sought to create were not, by and large, jobs for existing unemployed San Franciscans. The development and growth was designed to bring in new, higher-income workers from other places. This was intentional; at one point, SPUR, which was then known as the San Francisco Planning and Urban Renewal Association, stated that the city needed to change its demographic to a “standard white Anglo-Saxon” mix.

San Francisco has a rent-stabilization law. It only limits rent increases when a tenant stays in a unit; once that person leaves, the rent can rise to market rate. That means landlords have a huge incentive to get rid of long-term tenants.

The Board of Supes tried in the 1980s, with the leadership of the late Sup. Harry Britt, to extend rent controls to vacant apartments, which would have prevented some of that. The measure got seven votes; Feinstein vetoed it.

Years later, another board, with Agnos as mayor, passed vacancy control. But it was too late: The state Legislature quickly passed a law, known as Costa-Hawkins, that banned cities from enacting rent controls on vacant apartments.

Assemblymember Dominic Costa, who went on to serve in Congress, had tried to pass that bill numerous times in the 1980s, after Berkeley West Hollywood, and Santa Monica enacted vacancy-control laws. Every year, it passed the state Assembly, where Willie Brown was the all-powerful speaker. Every year, it died in the state Senate, where President David Roberti, who represented West Hollywood, made sure it never got to the floor.

Then Roberti was termed out. And Brown, who could have followed his lead and killed the bill, let it pass. Sure, he voted No, but he used none of his legendary clout to block it.

That made it impossible for cities to prevent displacement.

I spoke to Roberti a few years ago, on another issue, and he told me that Costa-Hawkins “was never going to happen on my watch.” Brown, who courted the real-estate industry for huge amounts of campaign money, wouldn’t protect tenants in his own city.

Add to that the Ellis Act, which lets landlords evict all their tenants and turn the units into the equivalent of condos, and you have a state-created crisis. (Brown never blocked the Ellis Act, either.)

Yes: Gentrification is a cause of homelessness. The vast majority of people living on the streets in San Francisco at one point had a home in San Francisco.

If cities in California had the right to protect vulnerable communities from speculation and displacement, and if any mayor of San Francisco was willing to do what it takes to make that happen (that is, ensuring that anyone who lives here isn’t forced out by someone with more money), we might see a lot less homelessness.

Meanwhile, while the developers ran rampant building offices, progressives, the much-maligned folks in this book, did everything possible to demand that new offices be linked to new housing. But for years, and even today, the Mayor’s Office opposes the idea of charging developers the full costs of their impacts.

The idea of mandating some affordable housing as a part of new luxury development came from the progressive community (over the objections of the Mayor’s Office). The idea that new office development should be directly linked to the provision of workforce housing came from the progressive community, and was dismissed by several mayors.

Generations of mayors have followed the neoliberal mantra that the free market will solve our housing problems. But developers in free markets seek only the highest return; for much of the 1980s and 1990s that was office space, so no housing got built. Today, it’s luxury housing, so that’s what gets built.

Oh, and over the objections of progressives, the Mayor’s Office encouraged Peninsula cities to accept huge tech offices and outsource their housing problems to San Francisco. The tech industry-loving mayors allowed the companies to charter luxury buses to take workers from SF to the Peninsula offices.

Shellenberger focuses on four major urban problems: homelessness, crime, drug addiction, and mental illness. These are, of course, all part of a larger crisis in the United States, one that goes back to the early 1980s.

Shellenberger tries to dismiss the role of the Reagan Revolution in creating homelessness, using only one metric—funding for the Department of Housing and Urban Development—while failing to mention the transformation of HUD from an agency tasked with housing the poorest of the poor to one supporting market rate developers and landlords.

To say he misses the point would be a rather profound understatement.

David Harvey, in his classic A Short History of Neoliberalism, brilliantly describes how the Reagan Revolution created a radically new approach to the social contract in the US. Heather McGhee, in The Sum of Us, equally brilliantly explains the racist history of how this country, in the same era, lost its ability to operate an effective public sector.

“Welfare” under Reagan became a racially-driven term used to convince white people that their taxes were too high. Under Paul Volker, the Federal Reserve in 1982 so shocked the economy that unemployment soared—at one point, more than 20 percent of Black Americans had no jobs—but inflation, which upset the bankers, fell.

The entire notion that human beings had basic rights to food, clothing, and shelter—which were built into the War on Poverty and Great Society programs of the 1960s—came under attack. And that approach to public policy hasn’t changed much in Washington, under either Democrats or Republicans.

Reagan also eliminated revenue-sharing, the program that guaranteed federal money to cities. In the meantime, the policies of racist, conservative post-war redevelopment agencies resulted in cities like San Francisco losing tens of thousands of low-cost housing that was never replaced.

Shellenberger argues that San Francisco provides more money in General Assistance to indigent adults than other communities. That only counts if you ignore Newsom’s signature Care Not Cash plan, which took most of that money away.

But here’s the reality: In 1981, when I arrived in San Francisco, a person with no job and no money could go to the welfare office and get about $350 a month and about $75 worth of food stamps. A room in a single-room occupancy (SRO) hotel was about $30 a week. So people on General Assistance could stay off the streets and eat.

Some of them used drugs and drank alcohol. Some had mental health issues. But they didn’t live in tent camps and shoot up on the streets; they had a roof over their heads.

Now, Shellenberger asserts, welfare recipients in SF get around $550 a month. What a bonus! Index that with the cost of living, and the obvious fact that even the whole $550 won’t pay for any type of housing in the city, and you see why there is so much homelessness.

Prop. I, promoted by progressives and passed in November 2020, offers more than $100 million a year for the city to buy up existing housing and take it off the market. The mayor has refused to spend the money for that purpose.

The progressives on the Board of Supervisors passed a measure during the height of the pandemic that would have provided (empty) hotel rooms for every homeless person in the city. The mayor refused to implement it, and Project Homekey, as it is called, ended up housing around 3200 people rather than the 8000 the supervisors wanted.

Wes Enzinna in The New York Times points out the long list of factual problems with San Fransicko. Among other salient points, he notes:

According to experts, as many as 30-40 percent of San Francisco’s unhoused may suffer from some form of mental illness, but addiction and mental illness are often the result of homelessness, or are greatly exacerbated by the stress of living on the streets, not its root cause.

I want to go a step further. Pretty much everything that has sought to make a positive impact on housing in San Francisco, from rent control to Prop. I, has been pushed by progressives—and opposed by the people in the Mayor’s Office who were running the city.

Only a fool would argue that cities can solve these massive problems on their own. But the California Legislature, which is dominated by the real-estate industry, has blocked efforts by cities to prevent evictions and keep rent-controlled housing permanently. And the federal government has done almost nothing to fund the millions of units of non-market housing that are needed to serious address the crisis.

So cities are on their own. It’s a huge challenge that decades of neoliberal mayors have bungled.

Shellenberger argues that the solution is more “responsibility,” that cities shouldn’t allow people to (among other things) sit on the sidewalks. He favors mandatory mental-health or drug treatment for those who, to quote Bob Dylan, were “bent out of shape from society’s pliers,” and jail for those who refuse and commit (mostly minor) crimes. That’s not only inhumane; it’s never been successful.

Housing first—affordable living spaces with social services—does in fact work, according to the data. Buying or leasing 10,000 hotel rooms would get people off the streets (without forcing them into shelters, which are not only temporary but are in many cases similar to jails, with strict rules, curfews, and dangers that many, for good reason, reject).

Buying existing buildings that are at risk for displacement has a solid record. Protecting existing vulnerable communities from eviction prevents homelessness. Safe-injection sites, pushed by progressives for years and only now supported by Mayor Breed, have an excellent history of getting drug users off the streets (and keeping them alive).

Taxing the rich and thus reducing economic inequality also works wonders, according to the eminent economist Thomas Picketty.

These are progressive ideas. The people who really run this city haven’t given them enough of a chance.

So let’s stop blaming the progressives for the problems on the city streets. It’s the neoliberal mayors who made this happen.