Found footage horror is cheap, scary and easy to make. That’s both the best and worst thing about it. The ability of films like The Blair Witch Project and Paranormal Activity to exponentially recoup their budgets led to the horror market being flooded with cheap Queasy-Cam imitations in the 2000s, and the genre lived in the shadow of its poor reputation for most of the last decade.

Yet the rediscovery of great genre entries like Noroi: The Curse and Lake Mungo, plus the millennial and Gen Z fascination with degraded physical media and liminal spaces, has led to a more artful and experimental boom led by film freaks for whom “cheap, scary and easy to make” is an invitation to limitless creativity rather than just dollar signs. Related is the emerging “analog horror” genre, in which the degradation of old VHS tapes and hand-held camera footage stands in for the slippery and subjective view of reality intrinsic to horror film.

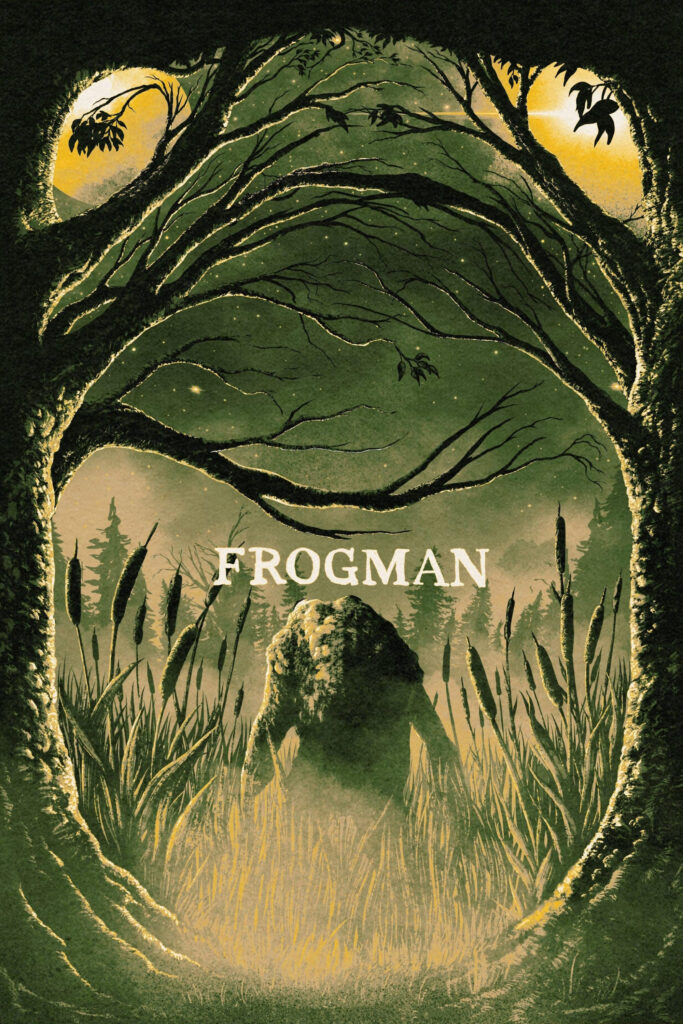

The films at last week’s Unnamed Footage Festival, which has taken place at the Richmond District’s Balboa Theatre every year since 2018 (except for 2020 and 2021’s virtual installments), embodied the joy of their making. Several of the films I saw were about creatives in some way. Anthony Cousins’ Frogman follows the video diary of an obsessed cryptid hunter in search of a legendary amphibian creature, while David M. Dawson’s Flesh Games documents a Jackass-style YouTube channel whose stunts veer into gnarly extremes of body horror. Even headlining film Trash Humpers, which essentially amounts to the director Harmony Korine and his friends donning rubber marks and wreaking havoc in the streets of Nashville, is basically a celebration of artistic freedom.

The Unnamed Footage Fest lasted from Wednesday/27 through Sunday/31. I attended with my partner Liam Brown, whose friend Harry McDonough shot the beguiling short film Red Leather Yellow Leather in just six hours, and was only able to make the Friday and Saturday festivities at the Balboa; other venues included the 4 Star Theater, also in the Richmond, and Artists’ Television Access in the Mission.

The first film I saw was Frogman, which has already been the subject of some Internet buzz for its magnificent poster and gloriously self-explanatory concept. I bought a Frogman shirt to wear the next day and was asked by several people if the movie was “good,” to which I still don’t really have an answer—and which I’m not entirely sure is a relevant question to a film such as this. The plot is implausible even by found-footage standards, and the “dramatic” scenes have the heft and subtlety of a TikTok skit, but the obvious joy Cousins and collaborators take in cranking the mayhem over the course of the film’s runtime made Frogman feel alive and immediate. It also gives us one of the more frightening horror protagonists I’ve seen recently in the form of Dallas Kyle (Nathan Tymoshuk), a scowling documentarian who takes the obsessiveness typical of found-footage protagonists to such volatile extremes we find ourselves wondering if he’s the real monster. (Frogman was preceded by Turtle?, a fantasia on conspiracy theories by the Chinese artist Yangqi Deng.)

The next film I caught was Flesh Games, which nails both the feel of late-2000s YouTube and the homoerotic grotesquery of the Jackass phenomenon. I’ve never seen a film more open about its characters’ bodily functions, giving the audience copious footage of the actors belching, farting, shitting, vomiting, and—of course—bleeding profusely. (Everything was real except the blood, the director confirmed in a post-film Q&A.) Lurking beneath the surface of the film is the social tension between shit-talking douchebro Jordan (Jordan Acosta) and ruddy-faced misfit Mike (Mike Miller), who seems driven to punish himself through his stunts. The film didn’t have much of an arc, with the inevitable slide into mayhem coming rather abruptly, but I later reflected that this is more true to how a film made of “found footage” would actually play—disjointed episodes with an abrupt and horrifiying ending, not a neat three-act structure.

It says something about the crowd that attends such a festival that Trash Humpers, one of the transgressive auteur Harmony Korine’s least-seen movies, can stand as some kind of aspirational totem. Shot on worn VHS, the 2009 film elevates the adventures of a sociopathic gang of feral seniors to some kind of statement about seizing the day. Its delight in its own unpleasantness is embodied in the Korine character’s constant shrieking, bawling, and shrill chanting; like the analog-horror lodestar Skinamarink, it uses grating sound design to keep the listener on edge. It’s the kind of film you “couldn’t make today,” if you get my drift; you will see Confederate flag decals and hear slurs and crude “Asian” accents. What took me by surprise was how joyful it all felt; the Trash Humpers seem to exist in their own universe, finding liberation through transgression.

Trash Humpers closed the night, with many nodding off to its virtually plotless drift despite the best efforts of Korine’s character to irritate the audience. The next day featured the hosts of the Mallwalk podcast, a sort of audio piece about the fictional Royal Galleria Mall in Belmont, CA and a tragedy that happened there one fateful day 20 years ago. Mallwalk rejoices in the aesthetics of dead malls and liminal spaces, with grainy VHS footage of food courts and video arcades soundtracked by plaintive vaporwave music. Then came a block of “analog horror” shorts with some true delights—the cosmic jumpscare of Skywatch, the increasingly worrisome doctor’s log of The Tangi Virus—followed by Blue Whale, a film from Russia.

Blue Whale is a “screenlife” film, meaning all of its action takes place on computer screens through Facebook messages, video chats, and files. The film follows a teenager as she attempts the dangerous “Blue Whale Challenge,” receiving increasingly deadly tasks from anonymous admins who threaten real-life violence against herself and her loved ones unless she complies. Though it’s debated whether the Blue Whale Challenge ever actually existed, cyberbullying is very real and so is the phenomenon of turning suicidal ideation into an “aesthetic.” You will see wrist-cutting, children throwing themselves off buildings, and sons and daughters being horrible to their mothers. This one felt a bit too real for me to enjoy, though perhaps that means the filmmaker has done their job. The announcer strangely promised “you’ll laugh, you’ll cry,” but I mostly just felt a pit in my stomach.

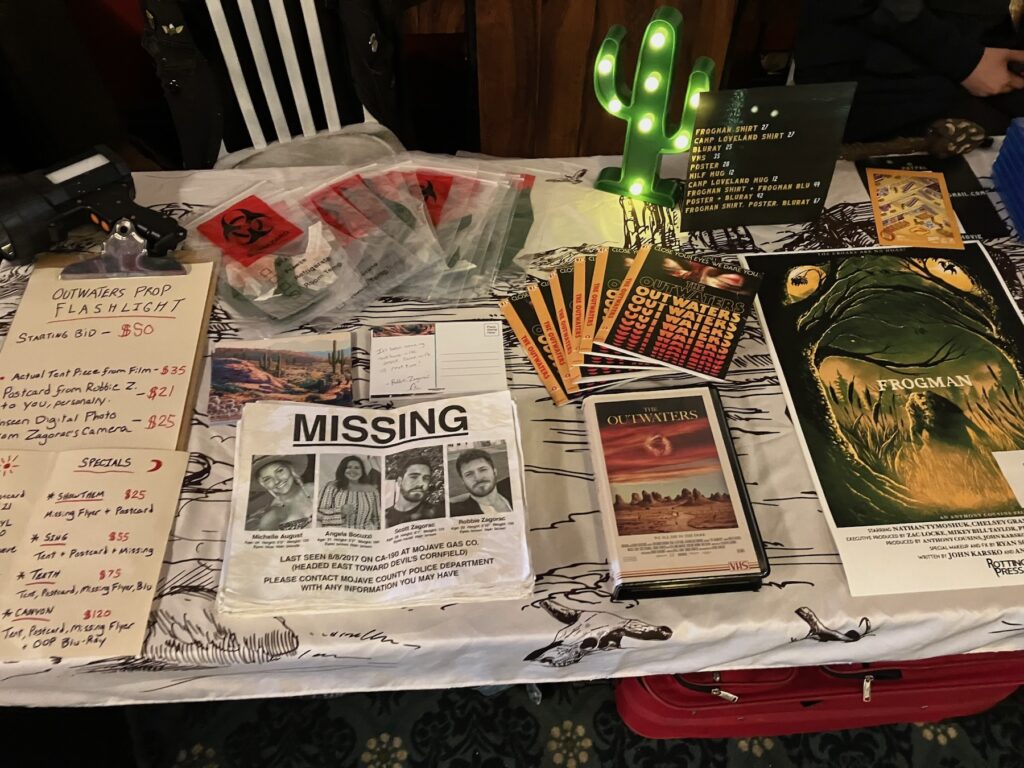

You may have noticed that many of these films draw their horror from the collective millennial memory bank—cryptids, Jackass, conspiracy theories, dead malls, vaporwave, VHS videos, Internet challenges. One other film in the festival, Mind Body Spirit, promised horror through YouTube wellness videos. Another, Robbie Banfitch’s The Outwaters, focuses on a group of LA hipsters who stumble through a phantasmagoric tear in reality while shooting a music video in the desert. (Banfitch could be found in the lobby of the Balboa, selling Outwaters and Frogman merch.)

This is one reason the found footage and analog horror movement feels so fresh: it’s one of the first I’ve seen that integrates millennial and internet-era pop culture in a way that doesn’t feel forced or self-satisfied. Most of the attendees and filmmakers at the festival were in their 20s and 30s, old enough to remember the texture of VHS tapes but young enough to be digital natives. The horror proceeds directly from their cultural context, and from the questions their makers no doubt pondered during long idle hours on the internet. What if Jackass went too far? Why do malls feels uniquely alluring and dangerous? Another question swam through my head after I walked out of the festival: Can I afford a camera?