Perspectives: This post is part of an ongoing feature column to bring some broader perspectives. This post is a collaboration with the Bay City Beacon.

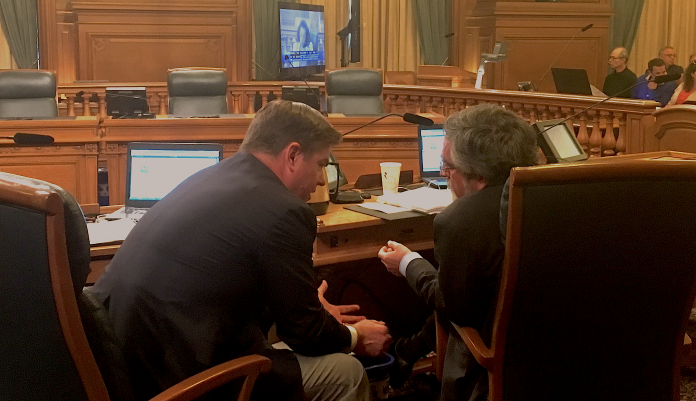

Competing legislation introduced by Supervisor Mark Farrell and by Supervisors Aaron Peskin and Jane Kim would change renters’ legal options for contesting an owner move-in eviction (OMI). They differ on several key points, and will be discussed by the full Board of Supervisors today.

Under California law, a property owner can evict tenants if they or their family members plan to live there. However, the property must be off the rental market for three years. If the landlord doesn’t move in – or moves in and then moves out — the evicted tenant has the right to return at the same rent.

One bill, sponsored by Supervisor Mark Farrell, would require property owners that carry out “owner move-in evictions” (OMI) to sign a declaration under oath that they intend to follow city’s existing eviction laws, and was passed without amendments yesterday by the Land Use and Transportation Committee. Some tenant advocates say it does not go far enough when it comes to enforcement.

Sups. Aaron Peskin and Jane Kim introduced their own bill that would extend the right-of-return restrictions from three to five years and allow nonprofit housing groups to sue landlords if the city fails to enforce the law. They also want to crack down on landlords who demand that tenants sign away their rights in exchange for “buyouts” that are never filed with the city. Some local property owners say the bill is too harsh on small landlords who depend on the income from their rental units.

The laws around OMI are hard to implement. Reports of fraud go uninvestigated, and OMI fraud cases are hard for the DA or wronged tenant to win, because the standard of proof is very high.

According to an investigation conducted by NBC Bay Area, more than 8,000 people have been evicted from their homes in San Francisco, with owner move-in evictions increasing by 200% in the past five years. Many of those evictions appeared to be fraudulent – the landlord never moved in.

Data from the Tenants Union shows that nearly half the landlords who filed OMI evictions failed to file the property paperwork with the city.

Farrell’s office is proposing that landlords provide additional annual “proof of tenancy” documents showing that they or a family member is living in the residence for the three-year period.

During the hearing, the committee heard from a long line of tenants who told horror stories about landlords fraudulently using OMIs to get rid of them. Families are facing displacement; longtime renters who refused to put up with mold and lack of habitability are getting OMIs in return.

But the committee moved forward only Farrell’s version, without key amendments. Those will come up at the full board on Tuesday, June 27.

In an effort to get some broader perspectives, 48hills and the Bay City Beacon are reaching out to people with whom we don’t always agree – in this case, Sonja Trauss, co-director of the California Renters Legal Advocacy and Education Fund (CaRLA), and founder of the SF Bay Area Renters Federation. Tim Redmond, editor of 48hills, also weighs in.

Sonja Trauss:

Currently, the Rent Board takes a random sample of OMIs filed each month and sends them to the District Attorney’s office. The DA is supposed to check in on whether the building owner or designated relative actually moved in and lives there, and if not, file charges. It’s already a misdemeanor to do a fraudulent OMI.

The DA never does these investigations though, because to win a case the DA would have to prove that the owner never intended to move in. It’s lawful for a landlord to change their mind for some reasonable sounding reason after the OMI and move out, or never move in in the first place.

The wronged tenant also has the standing to enforce the OMI rules, through a civil suit. This rarely occurs because, in addition to the difficulty the DA faces in proving the landlord’s secret interior plans, it’s hard for tenants to investigate who lives in their old apartment.

Supervisor Farrell’s legislation makes the penalty for fraudulent OMIing more severe. Supervisor Peskin’s legislation expands the universe of parties eligible to enforce the law to include non-profits like the Tenants Union. Neither proposal makes OMI cases easier to win or violations easier to catch.

Peskin’s legislation is an improvement over the status quo. Local tenant non-profits are slightly more likely to be able to detect a fraudulent OMI and are much better able to pursue a remedy when they do discover one. But local tenant non-profits are as overwhelmed as the DA’s office is with their own bread and butter issues – defending ordinary evictions and educating tenants on their rights.

The real solution for fraudulent OMI evictions is to outlaw this method of eviction altogether, which is perfectly doable at the state level. A complete repeal of Costa-Hawkins was proposed this session by Assemblyman Bloom. Tenant advocates inexplicably ignored it, and it died.

Ordinarily – throughout the US – once a tenant has a lease, if the landlord wants the tenant to leave, the landlord, or new owner, has to negotiate a buyout with the tenant. The tenant’s bargaining position is as strong as the length of their lease.

Because a rent controlled tenant in SF has the equivalent of a permanent lease, if OMI evictions were outlawed completely tenants would be in very enviable bargaining positions with respect to their landlords, new or old.

Tim Redmond:

If we banned all OMI evictions, it would absolutely bring property values down — only people who wanted to be landlords would buy occupied rental property. That would be a good thing (and I say this as a property owner). And we would prevent a lot of tenants from losing their homes. I am all in favor of taking housing out of the private sector entirely, and that would be a step.

I fear it won’t fly under state and federal law (generally, in capitalist America, if you buy a place you have the right to live there). But what the Supervisors can do is eliminate a lot of the fraudulent OMI evictions – the cases that we heard about over and over at the Land Use Committee today, where landlords toss out long-term tenants and then never actually move in.

The key elements to making the law work are not yet in the final language that the Land Use Committee passed yesterday. The City Attorney’s Office will never have the bandwidth to go after every bogus OMI, which is why advocates want tenant groups to have the right to sue when they find an illegal eviction.

The current bill, which will face some amendments today, also allows landlords to demand that tenants sign a document giving up their right to sue in exchange for a cash buyout. Tenants who are convinced that they will be forced to leave anyway often take those deals out of desperation – but if it turns out the landlord cheated and never moved in, they have no recourse.

The Committee today failed to include language that would say a landlord who violates the law (by not filing a notice of the buyout with the Rent Board, so the city can track it and also make sure there is no illegal condo conversion) would be unable to enforce the no-sue provisions.

The problem with a lot of what comes out of City Hall these days is that it sounds good – but has no teeth. Without strong enforcement provisions, the landlords will continue to cheat the system.

This piece was updated at 10:45 pm