The new Board of Supes starts its real work this week, and one of the opening events will be Question Time. The mayor can pretty much duck any debate if she wants, since the new supes were sworn in too late to make the deadline for submitting questions. But Sup. Gordon Mar tried to get a question in, and Breed could certainly address it if she wanted to.

Mar wants to know what the budget process is going to look like this spring. It’s not a routine question.

Mar has been involved for years with the Budget Justice Coalition, which seeks more of a role for community-based organizations in the drafting of the city’s spending plan. And his question is the first signal that, as a member of the board, Mar wants to see a more open, transparent, and democratic program for deciding which services are prioritized in Breed’s budget.

The mayor typically dominates the budget process, asking for budgets from departments (which go through commissions, most of which are controlled by the mayor) then shaping the direction of the first proposal. The supes Budget and Finance Committee gets a budget toward the end of the process, holds hearings, and makes what are usually minor changes.

Mar, it appears, wants to know if things are going to be different this year – if the community will have more input into the overall priorities and the specific funding plans.

We will find out by Friday/17where Board President Norman Yee is going to go with committee assignments. I would be very surprised if Sandra Lee Fewer doesn’t end up chairing Budget and Finance – and it would interesting to see her and Mar working together. Fewer (who used to work at Coleman Advocates) and Mar are probably the supes with the most experience fighting for equity in the city budget from the outside, as advocates. So they know the problems with the process well, and could be in a position to force some changes.

The Planning Commission hears a report Thursday/17on the state of the city’s economy and the housing “pipeline” – that is, the list of housing projects that are approved but not yet built.

You can read the report here. It includes some remarkable information.

The report notes that in the past nine years, during the long economic expansion, San Francisco added 170,000 jobs. That created a demand for at least 77,000 new housing units – a lot of them not at market-rate. And the growth has been very uneven:

In San Francisco, job growth has been led by the Information and Professional & Business Services industries, but the local and regional economy benefits substantially from overall economic diversity and labor availability. This diversity includes a substantial employment base and growth in Educational & Health Services and Leisure & Hospitality industries. Industries that have experienced lower or no growth include Manufacturing and Government Services. Employment growth also varies by race. The number of White, Asian and Hispanic San Francisco residents who are employed have all grown since 2010, while the number of Black residents who are employed actually fell, despite record job growth in the city.

That’s a pretty shocking statistic. In the tech boom, Black employment fell.

More:

Since 2011, construction jobs in San Francisco have grown by 50%, substantially more than overall job growth. However, construction employment (20,860 jobs in 2017) barely passed the pre-Recession high of 19,630 jobs (2008) in 2016, a much slower recovery than other industries. By comparison, office jobs started rebounding in 2011 and have far surpassed the previous peak, growing to almost 300,000 jobs in 2017.

The growth in education and health services and leisure and hospitality includes jobs that don’t pay enough to afford the new market-rate housing that’s been constructed. And there’s been nowhere near enough affordable housing built to address that need.

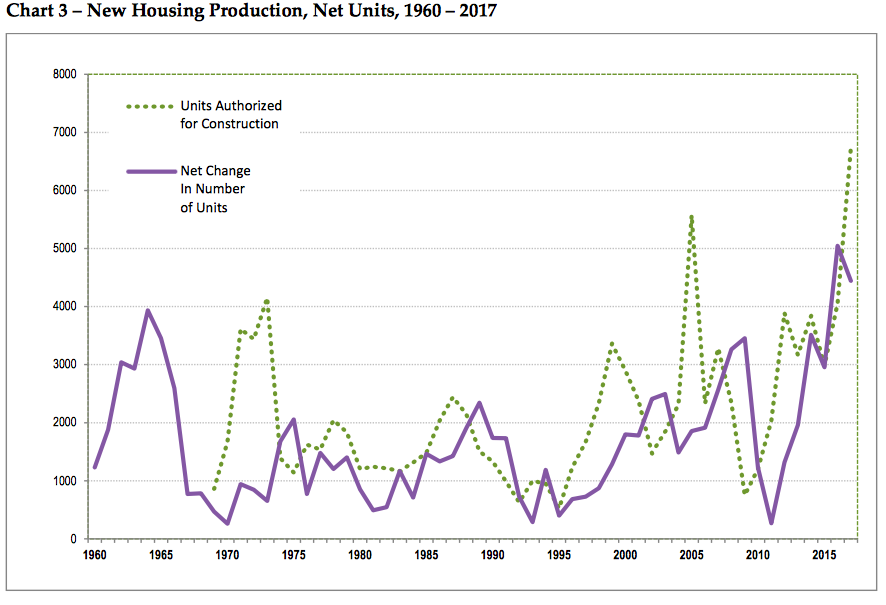

Meanwhile, a whole lot of housing has been approved – and not built. Check out this chart: In the past three years, the city has authorized the construction of almost 7,000 housing units – and about 4,500 have been built. In 2005, the city approved almost 6,000 units – and in the next few years, almost nothing was built.

That’s because the housing market involves a lot of factors that have nothing to do with whether San Francisco upzones neighborhoods or whether neighborhood opposition slows down projects. It’s all about investment capital and expected returns.

The report says that the current growth rate is going to continue into the next quarter, but

The city has seen more than nine years of job and revenue growth, which is a long cycle. This growth trend might change in the next two years and is very likely to change in the next five years, according to the City’s Office of Economic Analysis.

Nevertheless, the process of planning for growth – growth that is unsustainable and has already done terrible damage to the city – continues.

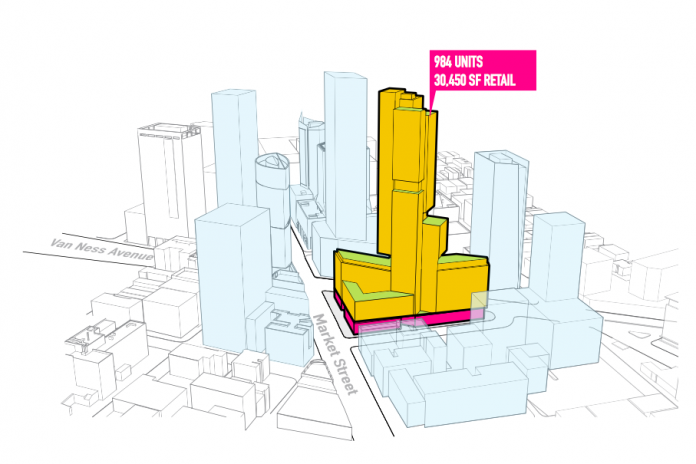

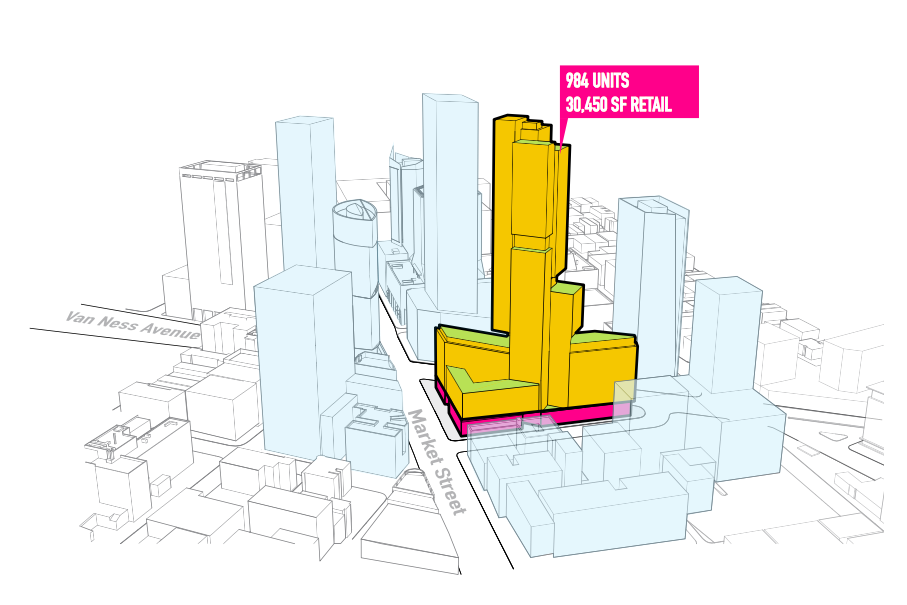

The same day, the planners will hear an informational presentation around a proposal to build a 590-foot market-rate residential tower with 984 units at South Van Ness and Market, on the site of an auto dealership. The proposal calls for “hundreds of units of affordable housing built on-site of financed off-site.” Under current rules, that could be as few as 177 units – far less than would be needed to offset the impacts of the new luxury units.

Market and Van Ness is a corridor well served by transit, and the new project would have very little parking. But the wealthy residents (if in fact, people who actually live here buy the units) will use Uber and Lyft, and get deliveries from Amazon, and order food from all sorts of places that involve someone driving to the door – and that intersection is already a traffic mess.

This will be the new highrise housing hub.

We know that it costs far more to build new Muni capacity than developers ever pay. So: More growth that doesn’t help anyone other than developers and rich people.

Welcome to 2019.