Last Friday’s release of a super deluxe edition of Prince’s Sign o’ the Times—featuring no less than 45 previously unreleased tracks and versions—has left it primetime to reflect on the surges and droughts of the artist’s career that led up to the iconic album, and the creative forces that gave it birth.

Take, for instance, 1987, when Prince was fighting the shadow of his success. Initially, industry types laughed at Prince’s idea for the cinematic version of Purple Rain. But it alone grossed over $70 million, not to mention earning the artist an Academy award for best song score. The record stayed at number one for 12 weeks, yielded five top ten singles, and sold nine million copies in the United States by 1985.

The public confirmed Purple Rain as a classic, but after Prince conquered its trifecta of (semi-)autographical film, album, and subsequent sold-out tour, Warner Brothers had high expectations of him for a repeat. Purple Rain‘s impact became a financial imposition that presided over Prince’s creative choices.

His next two albums with the Revolution Around the World in a Day (1985) and Parade (1986) were sonic rebellions. Their sounds ranged wielding from psychedelic pop, Middle Eastern sounds, European-influenced avant garde funk, and jazzy arrangements.

According to journalist Alan Light, Around the World in a Day was completed on Christmas Eve of 1984 and released in April 1985, just two weeks after the final date on the Purple Rain tour—which Prince cut short abruptly, after just six months.

“I sorta had an f-you attitude,” Prince told legendary Detroit DJ the Electrifying Mojo about his mood while recording Around the World in a Day. “Meaning, that I was making something for myself and my fans. And the people who supported me through the years—I wanted to give them something, and it was like my mental letter. And those people are the ones who wrote me back, telling me that they felt what I was feeling.”

Around the World in a Day and Parade hid treats for diehard fans of Controversy, Dirty Mind and 1999 that gave way to snarky inside baseball “try and follow me know” messages to the Purple Rain fanatics. Such newbies never understood, swaying their lighters in the air, that their stadium rock anthem was just some Bob Seger country twang flipped into an impactful ballad for the mainstream.

On “Pop Life,” you hear Prince trolling normcore:

What’s the matter with your life

Is the poverty bringing you down

Is the mailman jerking you ‘round

Did he put your million dollar check

In someone else’s box

Tell me, what’s the matter with your world

Was it a boy when you wanted a girl?

(Boy when you wanted a girl)

Don’t you know straight hair ain’t got no curl (no curl)

Life it ain’t real funky

Unless it’s got that pop

Dig it

Point is, the two subsequent albums after Purple Rain sold fewer copies, leaving the masses to catch up. Much to Warner Brother’s chagrin, Prince didn’t do sequels.

Minneapolis-born Prince Rogers Nelson’s ninth studio album Sign o’ the Times was his critical watershed moment—never to be equaled in his later career. He had simultaneously been working on a project he called Camille, an androgynous alter ego with his voice pitched to sound more womanly, and Crystal Ball, a rock-funk opera. Many of the songs and ideas on Sign o’ the Times‘ expansive 1987 double album were born out of sessions meant for different Prince works.

Before disbanding the Revolution—keyboardist Lisa Coleman, guitarist Wendy Melvoin, drummer Bobby Z, bassist Brownmark and keyboardist Matt Fink—in 1986, Prince and the band had recorded songs for a Dream Factory project that wouldn’t see the light of the day. Nonetheless, several songs from the session did later surface on Sign o’ the Times. Tracks “It,” “Starfish and Coffee,” “The Ballad of Dorothy Parker,” “I Could Never Take the Place of Your Man,” the eponymous “Sign ‘O’ the Times,” “The Cross,” “Slow Love,” and a late-stage remix of Prince’s constantly-reworked “Strange Relationship” all fall into this category.

“What people were saying about Sign o’ the Times was, ‘There are some great songs on it, and there are some experiments on it,’” Prince told Rolling Stone in a 1990 interview. “I hate the word ‘experiment’–it sounds like something you didn’t finish. Well, they have to understand that’s the way to have a double record and make it interesting.”

A large percentage of Sign o’ the Times was first recorded with the Revolution—but the fact is not fully reflected in the original album credits. The Revolution band was an under-mentioned phenomenon in itself, set amidst Reagan’s heavily conservative 1980s. This racially and gender-wise diverse band—the Revolution’s range in this sense recalling fellow greats Sly and The Family Stone—featured Wendy Ann Melvoin and Lisa Coleman, an openly queer couple, upfront and onstage. In fact, Melvoin and Coleman (who would later form the duo Wendy & Lisa) formed the creative brain trust Prince relied on most.

After The Revolution was dissolved, old band members would claim that while the Revolution had felt like a family, Prince’s other backing contingent, the New Power Generation, was more of a business—with Sheila E at its center.

Wendy and Lisa, along with Wendy’s twin sister Susannah (once engaged to Prince) and longtime engineer Susan Rodgers, collaborated and questionably brought out the best in one of the biggest artists of the 20th century. These women, their input—along with the Linn LM-1 drum machine—pushed his genius further.

Sign o’ the Times concentrated all these voices, ideas, experiments. It enhanced and showcased all of Prince’s sides; his writer’s brain and melodic vocabulary. He brought that sweet R&B of 1979’s Prince and 1978’s For You, and built on the rebel punk energy of Controversy and Dirty Mind. After playing to the middle with Purple Rain, Prince was free to unload some other ideas, different frequencies that encompassed the George Clinton/James Brown funk, through new personas. As the Black middle class was expanding in the ‘80s, so too did the ideas of what constituted Blackness. Sign o’ The Times was the auditory synthesis of these changes.

Daphne Brooks, professor of African American studies, American studies, and women’s, gender and sexuality studies at Yale, wrote a powerful essay for the liner notes of this year’s Sign o’ The Times reissue. There, she posits that Sign o’ the Times expressed the “nuances of those kinds of the paradoxical ways that Black life was unfolding at that moment.” Brooks finds evidence of the article conversation with the boom of Black independent cinema, the AIDS epidemic, Reagan’s racism, and the “crossover” trifecta of Michael Jackson, Whitney Houston, and Lionel Richie:

“… The Reagan/Bush regime was very much designed to restructure the Republican party, finally and resolutely, around racial polarization and anti-black structural reform, eviscerating the advances made by the Civil Rights Freedom movement. And then, of course, in Prince’s opening lines to “Sign ‘O’ the Times,” he reminds of the fact that we were in a pandemic then. The AIDS epidemic, which disproportionately — and again it’s eerie to use these words: disproportionately affecting black and brown neighborhoods as well as queer communities — it’s very present in the universe.”

The single “Sign O The Times” is a capital H, hit. Out of the box. No explanation needed. It offers a simple entry point into a dizzying complex record. Song “Sign o’ the Times” features a new maturity flowing from the artist’s pen. Direct social commentary, pulled from the headlines of 1986, it’s a continuation of Prince’s lyrical criticism of Ronald Reagan; a strain that began with 1981’s “Ronnie Talk to Russia” from Controversy. Nothing is left for interpretation. For some, the writing has been on the wall. Crack and AIDS, two issues on which Reagan and his voodoo, trickle-down economics, never declared war. (Just drugs.) That inaction left the country’s oppressed decimated by a national health crisis. Sound familiar?

Comedian Dave Chappelle, who also contributed to the liner notes of the super deluxe edition of Sign o’ the Times, remembers hearing the song for the first time:

“It was a spring day in 1987. I was listening to Casey Kasem on a local Dayton, Ohio, radio station. I remember being struck by the way Kasem introduced the song. He actually read the lyrics before he played the record. That really impressed me. When would you ever hear a DJ read lyrics on a Top 40 countdown? The words were profound:

In France, a skinny man died of a big disease with a little name

By chance, his girlfriend came across a needle and soon she did the same

At home there are 17-year-old boys and their idea of fun

Is being in a gang called the Disciples

High on crack and totin’ a machine gun

“I didn’t realize it at the time, but in hindsight, he was singing about what would be the two definitive crises of my generation: Crack and AIDS. Our story was being told in hip-hop, but as a genre, it was still in its infancy. Prince was the first mainstream artist to wax poetic and tell our community’s story, establishing himself as one of the preeminent lyricists for my generation. He literally was a sign of the times.”

The sweeping personally- and socially-minded double LP presents an African American singer, songwriter, musician, and record producer widely regarded as one of the greatest musicians of his generation. Prince drained every ounce of his own creativity and that of collaborators in one of their most artful periods, into 16 songs. He accomplished alongside working with the Time, Vanity 6, Shelia E, and Madhouse, plus crafting the various singles he would write for The Bangles, Sinead O’Connor, Joni Mitchell. Prince even played keys on Stevie Nicks 1983 hit “Stand Back.”

The creativity flowing out of Prince was non-stop and Sign o’ the Times captures the chameleon-like aptitude that he’d been working toward since joining Warner Brothers on June 25, 1977.

Since the ‘70s, Prince had been instructing top brass executives not to promote him as a Black artist—meaning, he’d studied how major record companies at the time unloaded budgets to promote rock (white) artists and then used whatever funds were left over to promote urban (Black) artists. His choices—from Controversy to 1999, the whole lingerie thing—were promotion shock tactics. They worked. Parade, the soundtrack to the critically bashed Under The Cherry Moon was viewed as a creative comeback after the mainstream confusion of Around The World In A Day. In the New York Times, John Rockwell wrote that Parade succeeds in part because of the more aggressive songs, “in which Prince chooses to play up the Black side of his multifaceted musical sensibility.”

Let’s remember that.

Sign o’ the Times came loaded with dense eccentric left-field turns, selfish insider’s snark, and sonic complexity. It provided and duped us all at once with an accessible entryway to rock, pop, gothy synth exercises, expanded funk universe, and experimental ying-yang eclecticism.

Nobody was doing breezy conversational mood funk pieces like “The Ballad of Dorothy Parker” or pondering the idea of getting closer to your partner “If I Was Your Girlfriend”. These are narrative masterstrokes that documented Prince’s own experiences at the time. These collections were his Stevie Wonder version of “Song’s In The Key of Life,” fed by that beloved Linn LM-1 and MTV.

The Sign o’ the Times Super Deluxe Edition unloads ideas, previously dropped projects, and experiments that the label did not think they could convert into pop success. Its 92 songs clock in at 8 hours and two minutes. It’s Prince all day for sure, all but confirming those 1980s rumors about him having 500 to a thousand songs in the vault. Dude wasn’t lying. What leaps out most from SOTT is that it is the zenith of Prince’s seven-year run of covering many forms of youth music; Funk, disco, pop, synth-wave, experimental but most definitely rock & roll.

Similar to Motown, this era of Prince presented generation as his genre. He snatched rock back for Black folks and made the contemporary guitar slingers—mostly white dudes—look like greenhorns.

Take for example his guitar-driven “I Could Never Take The Place Of Your Man,” which became the first Prince single to chart pop but miss the R&B listing completely. Me, I wasn’t really struck by it when it came out. Thought it was ‘aight, cool. But I was fiending for more “Housequake,” “Anotherloverholenyohead,” “The Ballad of Dorothy Parker,” “If I Was Your Girlfriend,” more “Gonna Be a Beautiful Night.” Joints that slapped. Sometimes maturity corrects vision to appreciate chess moves.

Much like the small-town, guitar-driven Americana narratives written by Bruce Springsteen and Tom Petty in the late ’70s and early ’80s, “I Could Never Take The Place Of Your Man,” originally written in ’79, tells the story of abandonment. A woman hits on a man in a bar, dances with him, and then presses if he can be a part of her home that has a baby and another one on the way. Her partner recently left her alone. Prince states that he’s not into that role although he “might be qualified for a one night stand,” which changes later in the song to “You wouldn’t be satisfied with a one-night stand.” Covered years later by Goo Goo Dolls, Flesh For Lulu, Sigue Sigue Sputnik, Seattle band Fruit Bats, and others, Prince crafts his own USA story. You can insert any ethnicity, the story sticks. It’s small-town friskiness on a Friday night.

Some white critics had difficulty seeing that this was Prince’s “Jack & Diane,” written before John Cougar Mellencamp ever penned that song with its iconic, MTV-ready line; “Sucking on chilli dog outside the Tastee-Freez.” These critics had difficulty separating the steak from the sizzle, couldn’t hear Prince reinventing his own version of what rock could be. The ever stately Kurt Loder remained locked. Not shook. Calling it “the most irresistible guitar-rocker Prince has done since 1980’s ‘When You Were Mine.’

The single was a svelte coup that garnered equal radio play. Prince weaponized a song to hold ground with Bruce Springsteen, Tom Petty, and John Cougar Mellencamp in the pop-rock radio format. Phil Collins, with his cut-and-paste, wonky-funked “Sussudio,” scored a hit with a low jack microwave reheat of “1999.” Peter Gabriel didn’t necessarily steal a Prince sound but you can hear some type of influence on the dance-rock hit “Big Time,” featuring Steward Copeland of the Police on drums. Gabriel rode the same influence to pen a satirical reading of the ‘80s, “Big Time,” where excess became the new normal. But Prince never had time to wait for folks to catch up. He kept working on the public imagination, staying five blocks ahead. Musically and in presentation.

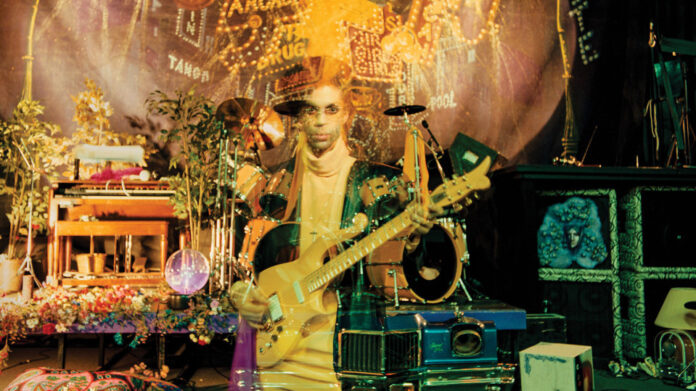

Looking back on the era, Jeff Katz, Prince’s personal photographer from the time, said Prince stayed ready.

“When I wasn’t shooting Prince, I was photographing every single ’80s hair band, like Bon Jovi, Def Leppard, and Ozzy Osbourne, and a lot of musicians that have their shtick basically look the same at age 20 and 85. But Prince was a chameleon. When he would switch eras, he would literally change everything, from his wardrobe to the way his rooms were decorated. As an artist, I couldn’t ask for anything more. He would show up at a photoshoot wearing what you would think was the stage outfit, and that would be his street clothing. There was no difference. Most artists have a stage persona, but he was looking like that in his house when no one else was around.”

Prince created Sign o’ the Times before becoming a solo act, and after disbanding the Revolution. As he told Rolling Stone in 1990, “What if everybody around me split? Then I’d be left with only me, and I’d have to fend for me. That’s why I have to protect me.”

That protection mounted into the pressure of releasing a hit album as a solo artist again. His record sales had been slowly fading, especially in the States. He didn’t want people to believe he had been relying on the Revolution to provide the hits, so Prince embarked on another never-to-be-released album Camille. After stumbling into a recording technique of slowing tracks down, recording vocals in real-time and then speeding the tracks back up again, Prince had figured out a way to record high-pitched vocals and came up with the album title’s pseudonym. It is quite peculiar that he would create a female persona just after firing the two most influential female contributors in his creative circle. Melvoin and Coleman were his in-house Lennon and McCartney-like peers.

An entire album of material was recorded in less than 10 days, and promos were even sent out to club DJs—but again the album was scrapped without any clear reason. Perhaps worried about the sales potential of the album and desperate to deliver a hit, Prince moved onto his most ambitious album to date, a triple LP magnum opus named Crystal Ball.

Twenty-two tracks were recorded in a matter of weeks, and the album was ready to go. However, Prince’s label Warner Music disagreed and refused to release the album. This would be one of the first major steps towards his messy public fallout with the label and Prince’s claim that he was under a slave contract; unable to release the music the way he wanted. Warner claimed a three-record set was too expensive. No one denied his genius, but a project just aimed at critics and die-hard fans would confuse (and I’m paraphrasing here) the Purple Rain crowd. Chief executive Mo Ostin insisted that Prince’s next album be no more than a double.

So Prince, in true polymath form, whittled 22 songs down to 15, recorded a last-second scorcher of a hit, “U Got The Look” with Sheena Easton. Slimming the album down to a double resulted in the song “Sign O The Times” being pushed to the front of the album. Only Prince could reduce something into profundity. This timeless, wide-sweeping masterpiece of pop conventions and genre-pushing experiments was recently dubbed by Rolling Stone as the 45th best album of all time. With the new super deluxe edition, we get its full breadth for the first time, a unique testament to Prince’s vision, the significance of the Revolution, and a proper bookend to his most magical era.