In 1964, the American singer Nina Simone released her single, “Pirate Jenny”—a ballad about a working-class woman who works at a posh hotel near a harbor. The lyrics describe a maid who is laboring under the noses of wealthy businessmen, who disregard and scoff at her presence. The woman looks out the window and sees a large ship looming in the foggy distance, but no one else seems to notice.

As the narrative progresses, a plot twist reveals that the ship—known as “The Black Freighter”—is filled with a pirate mob who ransack the city for all its wealth. The once powerful men become their targets, and, in the ultimate volta, the woman protagonist turns out to be the captain of the pirates, declaring her overthrow of the elite bourgeoisie.

Ultimately, the song represents an age-old truth: When wealth and prosperity is unequally distributed for some, the “have nots” will find a way to level the playing field, by any means necessary.

It is in this spirit of creative rebellion and urgency—and in the lineage of so many other radical cultural and arts movements of oppressed peoples around the world—that San Francisco’s newest literary outlet, Black Freighter Press, has been birthed. And like Nina Simone, their songs refused to be silenced.

Co-founded by San Francisco’s current poet laureate Tongo Eisen-Martin, and multidisciplinary writer Alie Jones, the two literary figures and community advocates are aiming to provide a transformative space for diverse voices in the Bay Area, and beyond, who might otherwise be overlooked by traditional institutions.

“There is a spiritual objective here,” Eisen-Martin says. “The idea came from conversations with folks who were frustrated and anxious and felt shut out, but because these poets are such good people, their frame was always ‘what can I do different?’ And I would think to myself, you don’t need to change, you just need a break, an opportunity. Seeing the general powerlessness that comes from not being able to facilitate and produce your own cultural reality, that’s where our mission comes from. We’re just trying to do our part to help.”

The two-person team works to solicit, publish, and promote historically marginalized voices— including inmates, Black, Brown, and Indigenous activists, and working-class writers—who perhaps never had the time or funds to pursue college degrees in creative writing. At Black Freighter Press, it’s about honoring the legacy of healing and empowerment through literature by creating a network of artistic support in order to platform those who haven’t always been given access to an otherwise selective process.

“When I talk to most writers of color, they feel like this industry doesn’t see us and no one will put us on,” Jones says. “So it was about putting ourselves on, and I think it’s important for folks to see us doing this. How many Black publishers do we know in this area? In this state? In this country? It’s not just a matter of representation; this is about propelling radical imagination.”

Jones isn’t hyperbolizing, either. Recently, there has been a large outcry among writers and publishers on social media regarding the lack of diverse representation in the field, which has given birth to movements like “Dignidad Literaria” (“Literary Dignity”) and a call to restructure esteemed literary journals—including POETRY Magazine—in order to dismantle white, institutional supremacy that seems to be embedded in the outdated and exclusionary editorial models.

It’s no small thing then, especially in this climate, that Black Freighter Press has arrived on our literary shores to embody a new wave of radical publishing in the Bay Area, which is dealing with aggressive displacement, rampant gentrification, racial segregation, and general neglect of low-income communities.

According to a study done by UC Berkeley, San Francisco’s Black population has been nearly cut in half since 1980, from 86,190 to 45,886—despite the city’s overall increase in population size during that same period. Additional data, collected over 40 years by the San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency, reveals that there are two San Francisco Bay Areas: one where certain groups of citizens can happily profit from and enjoy while living in increasingly desirable neighborhoods, and another, where mostly families of color, immigrants, working-class, and/or homeless residents are forced out of daily and are struggling for basic rights and visibility.

This warped reality of inequity is where Black Freighter anchors itself, and where it’s publishing from.

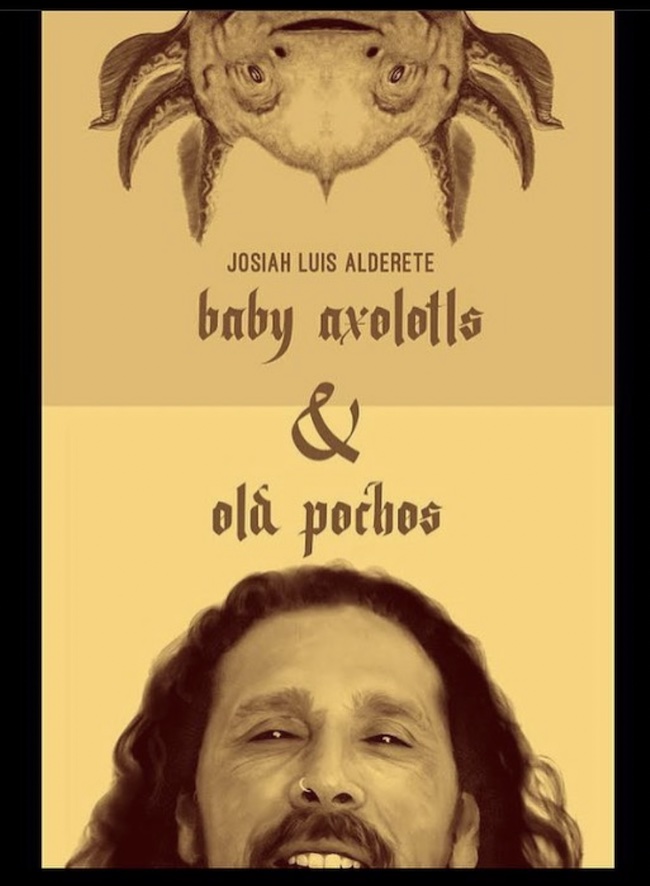

One such writer who represents the press’s spirit of the people is Josiah Luis Alderete, a community member Eisen-Martin describes as a “medicine man” who has spent most of his life living in San Francisco’s Mission District, East Oakland, and now, North Richmond. His book, Baby Axolotls y Old Pochos, will be part of the press’s official debut launch—along with QR Hand’s Out of Nothing—on April 29 (both books are currently available for pre-order on BFP’s website).

“Part of my poesia is like a pocho history, telling stories that I think might not get otherwise told, or misinterpreted, or purposely re-interpreted by other gente,” Luis Alderete says about his upcoming debut. “I’m not writing about giant revolutionary eventos, but just everyday eventos that are happening here on 24th St. or in North Richmond, things you might see on the corner. We got to tell our own stories and sing our own songs. It’s part of the resistance of saying how it really is.”

An employee at City Lights Bookstore, Luis Alderete is truly a community pillar for the Latinx literary circle in the Bay Area. Having established himself in the mid-90s as part of the collective, “Molotov Mouths”—an “outspoken word crew” from the Mission District in a time when the area was still predominantly immigrant and working-class—Luis Alderete would often perform at intersections around the city, meeting other artists who would express themselves freely before they were all priced out of San Francisco. Nowadays, none of them are able to afford living in the City, but as Luis Aldrete puts it, “we still return to our pueblo.”

Though no longer in the Mission, Luis Alderete continues to build space with intentional community-building as the founder and host of the “Speaking Axolotl” reading series, which has been a gathering place for diverse Latinx poets around Northern California for three years, a venue where writers like him and many others who otherwise might not be given the societal recognition to share their poetry with an audience can cultivate a sense of home among one another.

After 30 years of operating in, and helping to cultivate these alternative spaces, Luis Alderete has now been given the opportunity to publish the first collection in his life—thanks to the diligent work and funding of Black Freighter Press.

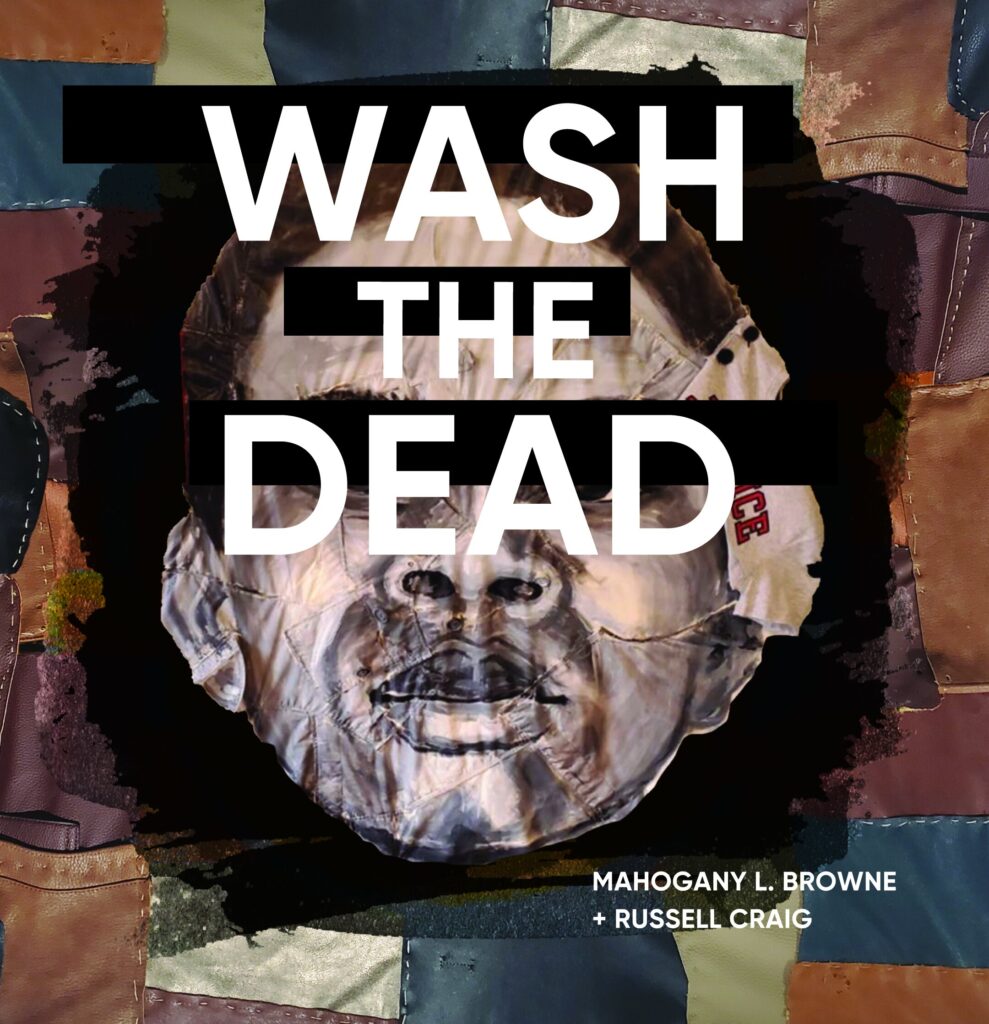

But he isn’t the only one. The press has also published a limited-release of Mahogany L. Browne’s Wash The Dead, a collaborative project with formerly-incarcerated illustrator Russell Craig, which is “an investigation of the mass incarceration pandemic through the eyes of its survivors, and a culminating response to the space Art for Justice Fund has cultivated for these difficult conversations.” It’s a form of resistance through the literary arts that, in spirit, is inspired by groups like the Black Panthers, United Farm Workers, and Zapatistas.

“Along the lines of so-called ‘Third World Revolutions,’ it’s about setting up liberated territories, and priming liberation through cultural efforts and education,” Eisen-Martin explains. “In looking at how you can build social autonomy in the face of such severe white power structures, what kind of space is that? What does it look like for a publisher who doesn’t own anything and doesn’t police and gatekeep anything? I think that’s where the press exists. It’s that process of taking ideas and putting them into books and getting these books around. It’s a legitimate slice of self-determination.”

In speaking with Eisen-Martin, Jones, and Luis Alderete, it’s is evident that Black Freighter Press isn’t about one singular person or one singular objective—rather, it’s an intricate and layered scaffolding of revolutionary and expansive beliefs built from complex histories, with a desire for autonomy and liberation of the self.

“We want to honor our authors and their voices,” Jones declares. “Josiah embodies this trilingual magic, for example. At another press, he might have been told to scale back on certain moments in order to make it more ‘palatable’ to a mainstream audience. But we embrace all of his richness.”

Eisen-Martin also adds that the press is designed to “protect” their contributing writers by giving them 60% royalties and ensuring they are not exploited or tokenized for their narratives in any way. Both Eisen-Martin and Jones—who are Black artists with Bay Area roots—see it as sacred work that can help to shift the capitalistic model that the U.S. writing industry is contingent upon.

The writers working with the press are equally invested in this movement. When asked about his upcoming publication, Luis Alderete admits he was “scared” at first, but found comfort in the genuine support and advocacy of his press: “This is a Black and Brown collaboration. I feel safe and I feel strong,” he tells me.

It’s a feeling that comes across in everything related to Black Freighter, whether publishing books, or hosting one of their regular reading events, known as “The Docks.” In the way Nina Simone sang about a time and place where her people could thrive with economic and social dignity by taking control of their destiny, Black Freighter is similarly pushing forward, with more voices looming on the horizon.

“We would like to have a cooperative model so that we are paying ourselves in ways that honor all our needs,” Jones says.

Like the subversive American poet and songwriter, Gil Scott-Heron, once declaimed, “the revolution will not be televised.” Rather, it will be published.

See more about Black Freighter Press here.