SCREEN GRABS Here’s something you don’t normally see mid-summer at the multiplex: Simultaneous openings of two movies with Emma Thompson. Neither are exactly Howard’s End, however, one being writer-costar Mindy Kaling’s Late Night, a Devil Wears Prada-type Boss From Hell comedy in which Emma plays an imperious TV talk show host. The other is Men In Black: International, the first film in that sci-fi comedy franchise without usual stars Will Smith and Tommy Lee Jones; instead, we get Chris Hemsworth and Tessa Thompson (no relation), with Emma returning as “Agent O” from MIB3. Elsewhere on the sequel circuit, we get Shaft, which is the second movie of that title starring Samuel L. Jackson—he also starred in the late John Singleton’s 2000 reboot of the 1971 “blaxploitation” hit. Those prior movies were fairly straight-faced, however, and word is that this one (from frequent Kevin Hart collaborator Tim Story) is more of a sendup.

Not a sequel but by all accounts waaaaaay too much like every other Jim Jarmusch movie is The Dead Don’t Die, in which a cast of the usual suspects (Bill Murray, Adam Driver, Tilda Swinton, etc.) stand around looking cool amidst a gory but comedic zombie epidemic. Jarmusch fans are very forgiving, but this won some of the worst reviews of his career in its Cannes debut last month. Not at all a flippant joke is the importantly named American Woman, an attempt to create a sort of epic of ordinariness, with Sienna Miller as a working-class Pennsylvania woman smiling through tears (if also yelling and drinking a lot) over the decades. But it ends up coming off more as a kind of heavy-handed soap opera, too often on the verge of working-class caricature.

Though SF Docfest comes to a close this Thursday (the 13th), the cosmos is compensating for that loss with a pileup of documentaries all opening this Friday for regular commercial runs. Two we didn’t catch in advance. One was Serengeti Rules, Nicolas Brown’s film about a particular scientific theory about ecosystems that is vividly illustrated in the titular African savannah. If you’ve been waiting for a movie about the wildebeest, your wait is over. The second is Dan Krauss and Crash helmer Paul Haggis’ 5B, about the San Francisco General Hospital ward that pioneered compassionate treatment of people with AIDS in the mid-1980s. The other new arrivals are detailed below. All open Fri/14 unless otherwise noted:

Hecho en Mexico

RoxCine’s second annual festival of new Mexican non-fiction cinema brings not just six diverse documentary features from south of the now-endlessly-politicized border, but also appearances by filmmakers and/or subjects from each at select screenings. Sounding particularly irresistible is Jose Pablo Estrada Torrescano’s Mamacita, in which his attempt to pay homage to a beloved 95-year-old grandmother uncovers generations of lurid upper-class scandal. Eva Villasenor’s M is another family self-portrait, this one training its eye on her famous rapper brother.

Nuria Ibanez’s A Wild Stream aka Una Corriente Salvje is a lyrical snapshot of two men united by their shared lives as fishermen on a remote beach. Likewise scrutinizing life at one with Nature is Yolanda Velasco’s Titixe, about the struggle to maintain a black-bean farm after its longtime patriarch’s demise, while Melissa Elizondo’s El Sembrador aka The Sower profiles a teacher’s instilling of humanistic values in her multigrade, rural Chiapas classroom. The most overtly political feature here is Jose Arteaga’s Recuperando el Paraiso aka Recovering Paradise, about indigenous communities’ struggle against the insidious influence of drug cartels. Fri/14-Sun/16, Roxie. More info here.

Asian Masters Double Feature Series

Because no San Francisco week should be completely without a film festival, or at least something like it, the 4 Star is stepping up to the plate with this two-week showcase for recent cinema from the Far East. There are two B&W features from South Korean director Sang-soo Hong, both released last year: Cafe-set B&W drama Grass, and the family reunion piece Hotel by the River. From Taiwan comes the epic 1992 Ming Dynasty action epic Dragon Inn, medieval 1973 swordplay saga The Fate of Lee Khan, and 1971’s similarly angled three-hour costume classic A Touch of Zen.

Reaching even further back are a pair from Japan. Kurosawa’s 1950 Rashomon almost single-handedly launched that nation’s starring role in the rich landscape of post-WW2 arthouse cinema. Taking a gentler but no less astute approach to drama was Ozu’s The Flavor of Green Tea Over Rice, released two years later. New currents in Japanese cinema will be represented by Ryusuke Hamaguchi’s acclaimed Asako I & II, which we’ll discuss next week (it opens Fri/21). Fri/14-Thurs/27, 4 Star. More info here.

It’s Only Rock ’n’ Roll

Well, it’s not only rock ’n’ roll: This PFA series also features reggae (1973 Jimmy Cliff classic The Harder They Come), soul (the same year’s concert documentary Wattstax) and hiphop (Dave Chapelle’s Block Party). But otherwise, yeah, it’s that crazy beat the kids just love, showcased in vehicles for everyone from Elvis (1958’s King Creole, arguably his best movie) to Bowie (Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars) and Talking Heads (Stop Making Sense). You can debate Beatles (A Hard Day’s Night) versus Stones (Gimme Shelter), or enjoy the sonic smorgasbords of Monterey Pop and The Last Waltz.

Some of these are free outdoor screenings, which is probably as close as you’re going to get these days to the once-ubiquitous summer youth experience of seeing movies at the drive-in. Although the latter venues surely never showed movies by rock-fueled experimental hedonist Kenneth Anger, or most likely the prickly 1967 Bob Dylan documentary Don’t Look Back. Illustrating the decline of western civilization that same year, Peter Watkins’ Privilege has Paul Jones as a pop star turned propaganda tool for fascists. Then there’s Penelope Spheeris’ actual 1981 The Decline of Western Civilization, the fabled snapshot of first-generation L.A. punk. Thurs/13-Sat/August 31. More info here.

Barbara Rubin and the Exploding NY Underground

Somewhere, somebody out there is probably even cooler than Barbara Rubin. But until further notice, the official Coolest Person Ever crown must go to Rubin, who merits the awe-inspiring description of “Experimental filmmaker who introduced Andy Warhol to The Velvet Underground.” As if that weren’t enough, this “middle-class Jewish teenager with a wild streak” also “did the visuals” for the legendary Exploding Plastic Inevitable multimedia show, dated Bob Dylan, was mentored by Jonas Mekas, got into Kabbalah mysticism several decades before Madonna, and was practically Mrs. Allen Ginsberg despite the inconvenience of his homosexuality.

Though a muse and connector for many other, better-remembered artists in the 60s, her own innovative work as an avant-garde filmmaker looks as fascinating as it is frustrating—she made lamentably few films, some of which are lost. She also had compelling mental health issues probably not helped by prodigious drug use, and dropped out of the “scene” in an abrupt, surprising way that still shocks the surviving friends interviewed here, half a century later. Like Nico: Icon, Chuck Smith’s documentary about another Warhol Factory figure is itself styled as a piece of 60s experimentalism, with lots of superimposed images and miscellaneous psychedelia. It’s a fine movie about a sorely neglected artist. Roxie. More info here.

Halston

An overlapping but very different strata of Manhattan creativity is recalled in Frederic Tcheng’s very entertaining documentary about the late fashion designer. Fleeing the midwest for NYC, he became a celebrity milliner for upscale department store Bergdorf Goodman—famously designing Jacqueline Kennedy’s pillbox hat for JFK’s inauguration—then broke out on his own at the end of the 1960s.

His success was stratospheric, yet never quite enough. This is one of those true stories in which talent, perfectionism, a mercurial temperament, drug use and reckless ambition created both a star and a spectacular flameout. Hitching his wagon to mass-market JC Penney, of all things, Halston was a control freak who unwisely obligated himself to corporate minders until he lost legal control of his own empire.

I generally find fashion-industry documentaries boring, but this one is juicy and colorful. From Warhol to Studio 54 (admittedly, that’s basically the same thing), Halston was always at the epicenter of where everyone else wanted to be. Among surviving pals interviewed here are Marisa Berenson and future movie director Joel Schumacher. Plus, of course, preeminent Halston customer/model Liza Minnelli, who still calls him “my best friend” and rather touchingly declines to discuss his substance abuse woes out of loyalty even decades after his demise.

Framing John DeLorean

Another, perhaps more disreputable figure of fabled success and excess was the former General Motors executive turned would-be independent automotive tycoon whose product was the most notorious bomb in that industry since the Edsel. John DeLorean was a handsome engineer duly born in Motor City. He’s already gone through half of his four wives when he left GM to launch his own car, named after himself—the impressive-looking if problematic DeLorean, which was immortalized in the Back to the Future movies. But by the time they were released, the company had already failed, and DeLorean himself arrested in an embarrassing FBI drug-deal sting.

That was a clear case of entrapment. But it’s less easy to excuse him from some subsequent chicanery, including a wee matter of a “missing $17 million dollars.” DeLorean appears to have been a talented, complicated individual undone by his own vanity and increasing financial desperation. The saddest part of this compelling documentary is the input from his now-grown children, who seem to have had their entire lives hobbled by this downfall. The weakest element is the filmmakers’ insistence on dramatic reenactments (with Alec Baldwin as DeLorean), and fourth-wall-breaking sequences with actors discussing playing real-life figures. That material is all very “meta” in a gratuitous way that makes a film about a fascinating subject more fussy and self-conscious than anybody needs.

The Decay of Fiction

The first and (so far) last time I attended the Berlin Film Festival, almost 30 years ago, it was utterly exhausting. I never got over jet-lag, the most memorable competition films were perceived as flops (notably Volker Schlondorff’s underrated first screen iteration of The Handmaid’s Tale), and the best movies were buried in the wide-open, non-competing marketplace—I saw Richard Linklater’s Slacker and John McNaughton’s (already long-shelved) Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer in glorified classrooms with almost no other spectators.

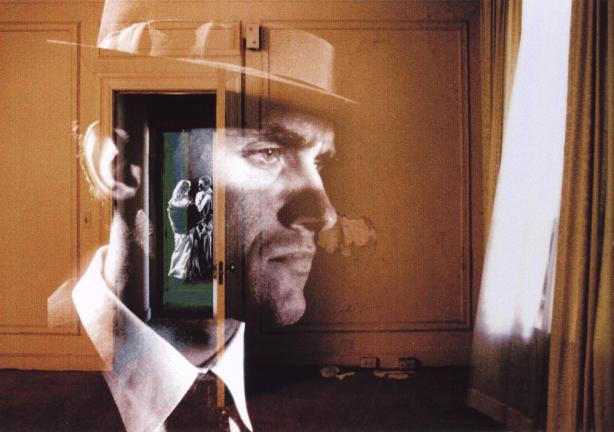

One movie that did stand out in the major competition was Pat O’Neill’s Water and Power, an hour-long stunner that told the story of arid Southern California’s battle for “water power” in an extraordinary mesh of experimental technique and archival footage. It was like nothing else, quite. You could say the same for O’Neill’s subsequent, sole feature, an act of ghost archaeology that might appeal to fans of Twin Peaks and Kubrick’s The Shining. The Decay of Fiction has been so little-seen it’s practically a lost film. It’s a fascinating whatsit in which the director’s artful juxtapositions create a noirishly cinematic meta-fiction blur. This very rare 35mm screening may well be your only chance to see the 2002 feature on the big screen. Sat/15, Roxie. More info here.