ONSTAGE Bay Area writer-performer Dan Hoyle, with his smart and poignant brand of journalistic theater, is at it again with his latest solo show, Border People (extended through August 30 at the Marsh). The 75-minute piece takes us on a journey into the lives of 11 characters who are straddling borders of culture, geography, and socio-economic class.

The characters in the show, all played by Hoyle, tell stories about the borders they’ve crossed, willingly or unwillingly, throughout their lives. The characters include an African American Navy vet who owns a food cart in Manhattan and tries to appease both white and Black communities by dressing in business casual while rocking Jordans; a deported HIV+ Mexican man who must choose between a dangerous attempt to get back to the US or dying closeted in Mexico; a temporarily US-situated teenager from Kabul who reflects on how the sunrise after his American high school prom reminds him of a sunrise the morning after he lived through a bombing in Afghanistan; and a gay, pagan farmer who lives off the land without electricity in Southern Arizona and occasionally helps Mexican migrants survive the border-crossing journey.

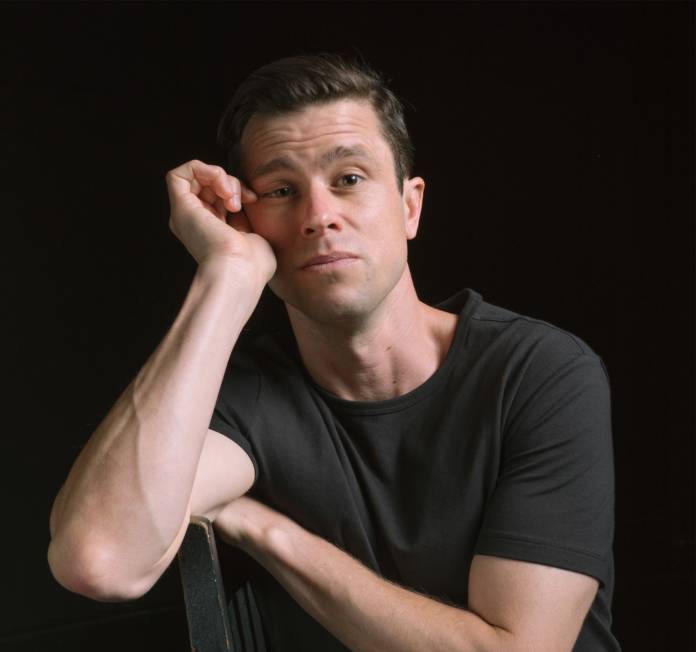

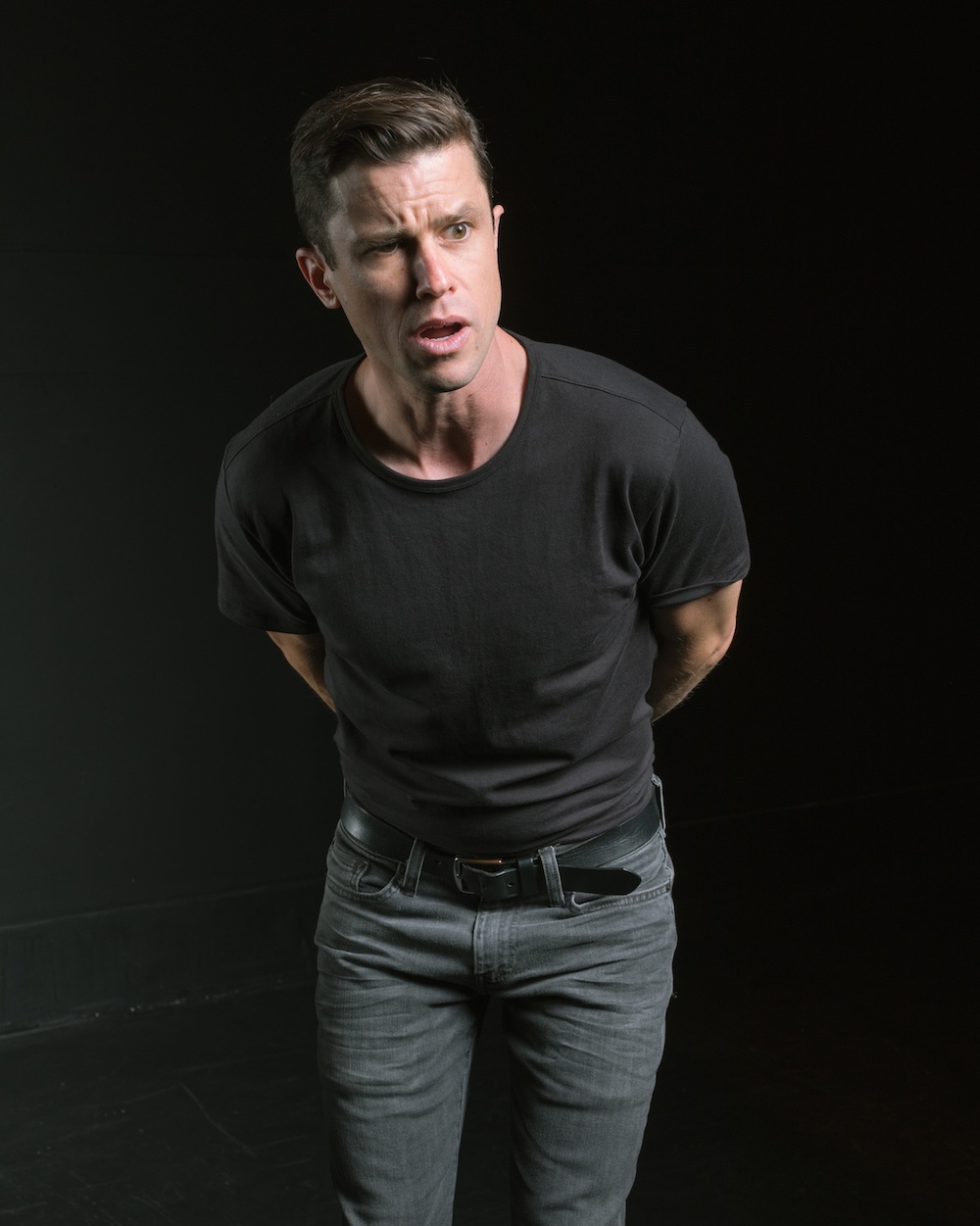

In a plain t-shirt and a pair of jeans, Hoyle fluidly morphs from one character to the next, sometimes speaking Spanish, other times taking on a strong accent or dialect, the portrayals so authentic that he seems to be channeling his characters rather than performing at all. In part, that’s because the characters aren’t fictional—they’re based on people he’s met in his travels; in part, it’s because, when it comes to performing, he’s simply that good.

Border People is Hoyle’s sixth solo show that’s premiered at the Marsh Theater, all of which have been based on live interviews he’s done with people from all walks of life. While he calls his work journalistic theater, it goes beyond both journalism and theater. He’s not simply telling people’s stories; he’s creating cross-cultural connection in a disconnected world, and asking us to do the same. I spoke with Hoyle, 39, to talk about his latest show, his life’s work to date, and his own experience with crossing borders.

KAREN MACKLIN You were introduced to theater at a young age through your dad, Geoff Hoyle, who is a prominent Bay Area actor. Is theater what got you interested in cross-cultural exploration?

DAN HOYLE Actually, it was growing up in the city and taking buses. We lived in Portrero Hill, so we’d take the 48—by the end of the ride, we’d be the only white kids in the back of the bus. Or when I would go to the park and play pick-up basketball. That’s the great thing about growing up in a city. Before you even know what’s happening, you’re all doing ethnographic research. You’re making friends and figuring out how not to piss each other off on the basketball court. I’ve always been more comfortable in environments where everyone didn’t all look like me.

KM So you decided to make theater out of your experiences?

DH When I was at school at Northwestern, doing straight theater didn’t seem as interesting to me as the theater of the street that I was locking into at the time. Northwestern is in Evanston, which is a suburb, and I missed city life. So I would take the train to Chicago at night and get off at some random stop and just kind of talk to people. It was my way to feel connected to something beyond the bubble that is any college campus.

KM Is that when you started creating the kind of solo shows that you do today?

DH Yeah. On Howard Street in Chicago, there was this basketball court I would go to play on, and I was the only white guy. At first, people would call me Dan Aykroyd and Wayne Gretzky, super generic white guy names. But then once I proved myself as a player, I started to get called The Professor. The guys were really cool and I ended up hanging out there a ton. That experience turned into my first performance. It was a 20-minute performance piece called Stuck Up: Hoops on Howard. “Stuck up” is slang for the ball getting stolen. That show was a big step for me. After that, came Circumnavigator, which was based on a trip I took around the world, and then Tings Dey Happen, which I developed after getting a Fulbright to live in the oil delta of Nigeria for a year.

KM It seems you’ve made a life out of intentionally placing yourself in situations where the culture, language, or societal norms are different from the ones you were brought up in. What’s important to you about having that experience? Does it feel like a spiritual calling, in some way?

DH I’m not really religious, but the longer I do it, there is a spiritual dimension to it. There’s something profound about the way I’ve been able to connect with people from massively different backgrounds on a really intimate level, and I want to encourage other people to do that. I think getting out of your comfort zone is one of the treats of being a human being. I’ve been doing it professionally for almost 20 years now. Also, I know everyone can’t just go out and do this, so I’m happy to give people that experience through my theater pieces.

Audience members often tell me they are moved to reach out in their own communities, or dive deeper into social justice or social service work, from seeing my shows. During one run of Each And Every Thing, we raised $3,000 in post-show audience donations to help a guy featured in the play to get secure housing and pursue his career in stand-up comedy. So that’s the point. To expand the empathy within us.

KM As a white guy portraying folks from all ethnic backgrounds in your shows, do you ever feel concerned about misrepresenting a culture or offending someone unintentionally?

DH As a white guy, I have a choice. Only portray my type, or portray a very diverse group of folks I’ve met. To me, the more interesting and inclusive answer is the latter. In order to do that well, you have to really do the research, you have to put in the time. It’s a real honor and it’s ethically complex to do this work, and I work hard to do it right. This involves being very transparent about what I’m doing with the communities and people I interact with, getting their permission to tell their stories, and developing relationships that often continue past the process of creating the show.

There’s a lot of conversation right now about cultural appropriation and I think that dialogue is important. And this type of work certainly can be done poorly and be a problem. But I do sometimes fear that people are so worried that they can’t understand each other’s experience that we don’t even try to understand each other’s experience. To me that’s not progressive. It’s a political and cultural tribalism that is happening on both the right and the left. I don’t think it’s healthy and it’s just not true to my experience. I hope my work shows that there’s another way to have cross-cultural interactions that are interesting and dynamic, and have value.

KM How do people react to your wanting to tell their stories on stage?

DH They’re often very excited. They feel pride and dignity in having their lives, which are often overlooked or ignored by our culture, held up onstage and acknowledged and celebrated as being meaningful. Several of the people whose stories I tell have been inspired to write their own story. An ex-militant in Nigeria, who is now a close friend, wrote his autobiography after seeing my show Tings Dey Happen in Nigeria.

KM Do you consider your work political?

DH Obviously, everything about what I do is tied up in political, socio-economic, and cultural questions. But it’s also about the humanity. I try to portray people in all their complexity. Like in Border People, one minute I’m talking to an older Black guy in the Bronx about police-involved shootings and the legacy of racism in America, and it’s super intense. Then the next moment, he’s laughing, saying he’s gotta go because his wife wants to get a fourth Teacup Yorkie. You don’t always see that in political theater. The complexity, the messiness.

KM Your last show, Each and Every Thing, asked timely questions about whether technology is robbing us of human connection. And your show before that, Real Americans, took us through the heartland of our country to better understand the diversity of views and opinions during political upheaval in the US. What inspired Border People?

DH I was an artist in residence at Columbia University between 2016-2017. Basically the charge was to create a new solo show. Then Trump got elected on my son’s first birthday. We’d hung up a happy birthday banner on the TV and it was still there as the votes were coming in later that night. I felt like I had to respond to this new reality.

KM Were you concerned about his immigration policies with Mexico?

Yes, but also all of the borders people cross every day in our country. First, I met Jarrett, the Navy vet who grew up in upper middle-class New Jersey and now lives in the projects. He was talking about the way he has to code switch by wearing khakis and Jordans. Then I read about the refugee safehouses on the Northern border of the US and learned that’s where people who were scared about their status were going, to try to flee to Canada, now that Trump was elected.

And I had been hanging out in the Andrew Jackson projects in the Bronx for a couple of years, too, and thought of that as another border because most people who aren’t from the projects don’t go into the projects. My exploration of the Southern border was last. I have a lot of love for all of the characters. They’re interesting, funny, and surprising. And I feel like I’m a border person, too, a culture border crosser.

KM You were born and raised in San Francisco. Do you feel like your work has been influenced by the city, itself?

DH As a kid, it was all mixed up here. I remember from a young age people would talk about their ethnicities. I had friends who were Mexican, Black and German, or Filipino and Irish. There was a strength and an honesty about it. San Francisco is a way different city today. I live in Oakland now and it feels more like San Francisco did in the ‘80s and ‘90s when I grew up, and I’m glad my son is going to experience that. But yes, there’s a kind of a fearlessness in the Bay, a hybridity and cross pollination of cultures that has always existed in a very organic way, and has always been understood as part of the culture. That’s huge and intrinsic to my work.

KM How has your work—and the stories of people you’ve met—affected you?

DH I carry all of these stories with me. I think about my friend See Know on the South Side of Chicago every day. I think about Okosi in Nigeria, about my Vietnamese translators in Vietnam, about the coal miners in Kentucky. After 20 years of doing this, all I know is that the only way to move through the world is to be more curious, open, and empathetic with everyone you meet.

BORDER PEOPLE

July 19-August 30

The Marsh, SF.

Tickets and more info here.