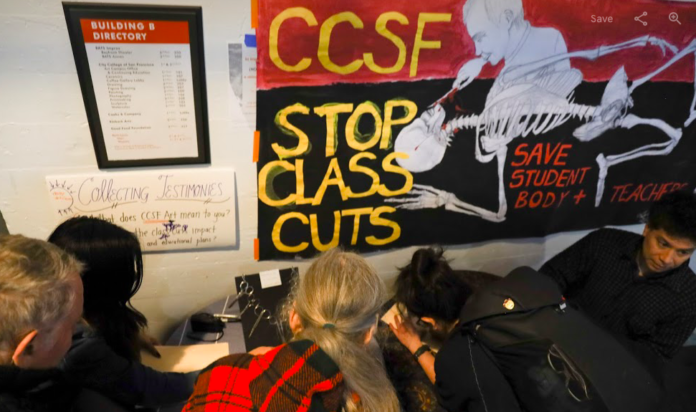

The sudden cancellation of 345 classes at City College of San Francisco on Nov. 20, the night before the school’s spring 2020 registration, prompted an outcry from more than 100 members of the college community who deluged the seats, aisles and stairs in CCSF’s administrative building Conlan Hall at the college’s Dec. 12 Board of Trustees meeting.

Public comment, limited to one minute per speaker, lasted nearly two hours. It culminated in a small group of students imploring the board to sign a document promising to undo the cancellations — an appeal that yielded no signatures.

Although CCSF has instituted class cuts over the last year to balance the school’s budget, the administration would previously discuss cancellations with the college’s 46 academic chairs because the latter plan course sequences as well as pathways to certification and graduation. But this time, there was no consultation.

“They just made arbitrary choices,” said Lorraine Leber, the chair of CCSF’s Visual Media Design department, when asked if she could identify any methodology behind the cuts.

CCSF Chancellor Mark Rocha stated in a college-wide email on Nov. 21 that the administration took “immediate actions to balance (the) budget” after learning the college would end its fiscal year with an approximate $13 million deficit and $3 million reserve deficit. CCSF spokesperson Rachel Howard said the administration prioritized keeping credit classes that graduate students of color.

Yet, scores of students — including many of color — found their certification or graduation halted. Moreover, despite the administration’s well-publicized plan to remove low-enrolled courses and keep higher-enrolled courses, many classes — particularly those related to the arts — had fully enrolled courses removed. Nearly 90 percent of classes designed for seniors were eliminated. And dozens of part-time teachers, given no notice, found themselves jobless next semester.

Members of the college community immediately advocated for emergency city funding with San Francisco’s top officials to restore the classes, a sum estimated by the college’s faculty union the American Federal of Teachers 2121 to cost $2.7 million. The budget supplemental proposal, up for vote in January at the earliest (unless Walton can get an emergency waiver of the 30-day hearing rule), has received public support from supervisors Shamann Walton, Gordon Mar, Matt Haney, Sandra Lee Fewer and Dean Preston; it would require an additional vote to approve it and three to override a mayoral veto.

To the horror of many in the college community, however, CCSF’s own chancellor emailed the mayor, board of supervisors and “San Francisco City Administrators and Partners” stating that he and his administration are “fully aware of the emails you are receiving from CCSF students who are appealing for funds to restore classes that have not been budgeted for the spring semester.”

“Please know that with the full support of the CCSF Board of Trustees, we are handling this difficult situation directly here at the college,” Rocha stated. “This situation is not an emergency but part of a long-planned restructuring of the academic program to prioritize the graduation of students of color.”

To boot, according to two emails obtained by 48 Hills, at least one supervisor has heard from CCSF’s Interim Vice Chancellor of Academic Affairs Dr. Edie Kaeuper that “the administration will not use any additional funds to reinstate the courses that have been cut for spring 2020.”

Walton, who is spearheading the emergency funding initiative, said it would be shameful if the college’s leaders didn’t use funding from the budget supplemental to reinstate classes. “This is our community college,” Walton said, adding that he thinks the city, with its more than $12 billion budget, can easily afford the small price of saving the classes.

“The classes were cut without community input and many of these classes serve students who are in need of job and skills training as well as older adults who are looking to acquire new skills,” Walton said. “Together, along with Supervisors Fewer, Mar, Haney and now Preston, we are fighting for an immediate solution to save City College’s spring classes that serve our community. I am reaching out to my colleagues in hopes of gaining their support for this important bridge funding for city college.”

AFT 2121 President Jenny Worley addressed Rocha’s email herself in an open letter to the Board of Trustees.

“We were stunned and horrified to learn that rather than support our efforts to address the budget shortfall, Chancellor Rocha instead attempted to thwart them by emailing the Mayor and Board of Supervisors to say that the college does not require bridge funding,” the union stated. “This assertion flagrantly contradicts the rationale the Chancellor gave for these cuts on Nov. 21, suggesting that the “crisis” was manufactured in order to justify the class cancellations.”

“A college spokesperson told us: “The College appreciates the work of the AFT and the Board of Supervisors. The College and the Board of Trustees will evaluate any funding initiative from the BOS when it is received. The preference of the College is to work towards long-term sustainable funding measures, such as the Community Higher Education Fund (CHEF) as proposed by Supervisor Gordon Mar, rather than one-time funding measures that do not help the College overcome its structural budget issues.”

We spoke to two College Board members, Tom Temprano and Board President Alex Randolph, and neither would commit to directing the chancellor to accept the emergency money. Both said that they would need to wait to see if the money is actually available.

Randolph told us he disagreed somewhat with the chancellor — “I think this is an emergency,” he said. But he would not promise to seek to save all of the classes. “Some of them needed to be cut anyway,” he said.

Separate from the supplemental, AFT 2121 is attempting to pass a Community Higher Education Fund, which would fund programs underfunded by the state of California down the line.

CCSF, which draws the majority of its funding from the state, has eliminated hundreds of courses each semester since fall 2018 to compensate for its financial deficit, estimated to be $32 million by the college administration at a Board of Trustees meeting in February. Because the college’s state funding is currently based on enrollment, administrators attribute the deficit largely to the college’s offering too many low-enrolled classes.

Urgency to achieve a balanced budget is heightened by the college’s need to avoid falling below the 5 percent minimum reserve required by accreditors, otherwise it risks losing its accreditation and triggering a state takeover, according to administrators. CCSF’s accreditors, who review the college’s accreditation every seven years, are due for a midterm college visit next year.

The college administration also blames the cancellations on California’s new funding formula for community colleges, which will distribute funding based on enrollment, low-income student count, certification and graduation, rather than primarily enrollment. However, that takes effect in 2021.

“Over time, this formula will force community colleges to favor class enrollments for students seeking degrees or credentials,” said Thomas Brown, an activist with Democracy for America.

Because of that, he said, other communities, like the elderly, will be left behind. Numerous college stakeholders have held similarly and questioned what lies in wait for San Francisco’s lone community college.

“For many decades the college has served as an institution of education and advancement (& rejuvenation!) for students from all walks of life, functioning as both a scholastic base and a central city resource of growth & healing,” CCSF professor Steve Georgiou stated in a letter to the campus community. “If these cuts are implemented, they change the educational mission of the school.”

However, for CCSF’s Administrators Association, which represents the interests of CCSF administrators, “right-sizing” CCSF is necessary.

“We must adapt or close our doors. The romantic notion that a community college has something for everyone is just not sustainable,” AA Co-Chair Jill Yee said at the Dec. 12 Board meeting. “We cannot be all things to all people. We unapologetically prioritize the needs of a first-generation college student seeking a degree over a student with a degree wanting to take an archery class.”

Older Community at a Loss

Abe Silverman, 89, performed slow, assured Tai Chi movements on Dec. 6 while ambient music played at the San Francisco Senior Center. The instructor called a break, and Silverman’s classmate David Kennedy joined him in the hallway. The topic quickly turned to age.

“See, you’re older than I am. I’m a young’un. I’m 82,” Kennedy said.

“Oh, you’re 82? You’re getting there. Don’t rush it,” Silverman replied.

“With luck, I’ll never catch up,” Kennedy quipped, smiling.

The two attend “Principles of Balance,” where older adults learn Tai Chi under City College of San Francisco’s Older Adults Department instructor Judy Hubble.

Silverman, a retired veteran who walks with a cane, enrolled after falling twice in the last year. He said the class has notably improved his mind-body awareness. And, while he normally walks with a hunch, Silverman now finds himself standing upright in class.

“I’m pretty sure that if I continue enrolling that I will see incremental changes,” he says.

CCSF’s Older Adults Department offers classes to more than 2,000 senior residents throughout dozens of centers across San Francisco, according to OLAD Department Chair Kelvin Young. These include hands-on courses in health and fitness, arts and crafts, music and theater appreciation, writing and literature and computer technology.

While classes draw numerous lifelong learners to centers, the students commonly stay for the people.

“I know the people. They know me,” Silverman said.

The night of Nov. 20, the college administration cut 52 of 58 of the college’s OLAD classes — about 86 percent. In a Dec. 11 letter to Rocha, Assemblyman Phil Ting urged CCSF to collaborate with local and state agencies to continue offering older adult classes.

“These are lifelong learners,” said Marilee Hearn, formerly a teacher with the San Francisco Unified School District, and a student of the program. “So what I see is an assault on lifelong learning.”

John Hedges, 77, a ceramics student at the San Francisco Senior Center, said what the program provides extends beyond education.

“This is my home away from home. I don’t know what I’m going to do when these are cut. It’s like they’re taking away my life,” Hedges said he’s heard many colleagues say at the center.

The center’s director Sue Horst, who’s spent 42 years working in senior centers, has seen firsthand where he’s coming from.

“It is well-known in research that older adults who are isolated and at home and who do not engage socially, who do not have a purpose, who don’t have a place to belong, are more susceptible to chronic disease and struggle in aging in place,” Horst said. “And when someone connects and comes to a center like this, it staves off isolation, it helps them age in place.”

The Older Adults Department works in coordination with more than 30 centers across the city, from community centers to assisted living facilities to hospitals, department chair Kelvin Young stated in a letter to the college administration pleading to have OLAD classes reinstated.

The community partnership between CCSF and these centers, some lasting for over 30 years, allows CCSF to bring the OLAD to seniors across dozens of neighborhoods without paying to lease facilities.

By eliminating this collaboration, the class cancellations cut deep into one of San Francisco’s fastest growing populations of older adults — currently close to 200,000 residents, Young said. Additionally, nearly 30 percent of students — more than 5,300 — are over 60 years old, according to CCSF’s 2017 demographics data.

If the classes aren’t reinstated, Young, Sue and others responsible for carrying out the program worry it will have numerous cascading impacts on the senior population. By attracting seniors to centers, OLAD makes them aware of other services the centers offer. For example, Sue said, the SF Senior Center has two women who speak Cantonese, Mandarin and English, and help people with issues like housing, transportation and the low-income food subsidy program CalFresh.

The elimination of these classes, besides causing centers to lose instruction, would decrease awareness of these and similar services.

“This vast cancellation of OLAD program for next semester will have a devastating impact to our students and community,” Young stated in his letter. “We implore you to consider the serious consequences of this schedule reduction and reinstate our classes for Spring 2020.”

Certification at risk

Scores of students learned Nov. 20 that they would no longer be able to graduate or receive their certificates due to required courses being cut, and department chairs scrambled to get them back.

Two cancellations in the VMD department — Infographic Design and Package Design — would have prevented numerous students from obtaining their graphic design associate degrees, Leber said. She traded a first-semester fundamentals course to get the two courses back, compromising the department’s future enrollment.

“It’s a deal with the devil,” she said.

Among those at risk of not graduating were international students, who must graduate by a set deadline, otherwise they risk becoming unable to stay in the U.S. They also pay $287 per unit, compared to the usual $46 for California residents outside San Francisco (for whom tuition is free).

VMD student Andrea Wrobel created a petition on Change.org, which expresses sentiments shared by many in the department and received 556 signatures as of Dec. 16.

“Cutting our pathway to graduation likely ends our future at CCSF, and within the United States,” the petition states. “It is financially impossible for most of us to stay on as a full-time student until these classes are offered in the future. Waiting is not an option.”

Though Leber bartered to reinstate two classes, some students still saw their certification delayed. One of the removed courses was an animation class required for the digital illustration and digital animation certificates. Although an illustration course can technically substitute, it’s a regular drawing class, and for at least several VMD students inapplicable to animation.

VMD student Nathan Burris had planned to earn his digital illustration and digital animation certificates in spring but now ponders which he should take before leaving school next fall — while worrying that the classes he needs to earn them won’t be available in time.

Working while attending classes, VMD student Katarina Aiken has spent three years working toward certification in digital animation. The animation course’s removal shocked her. Between school and work, she said, she hasn’t found the time to work with a counselor or plan for what’s next.

She said she doesn’t know if she will complete the certificate anymore.

Affordable arts diminished

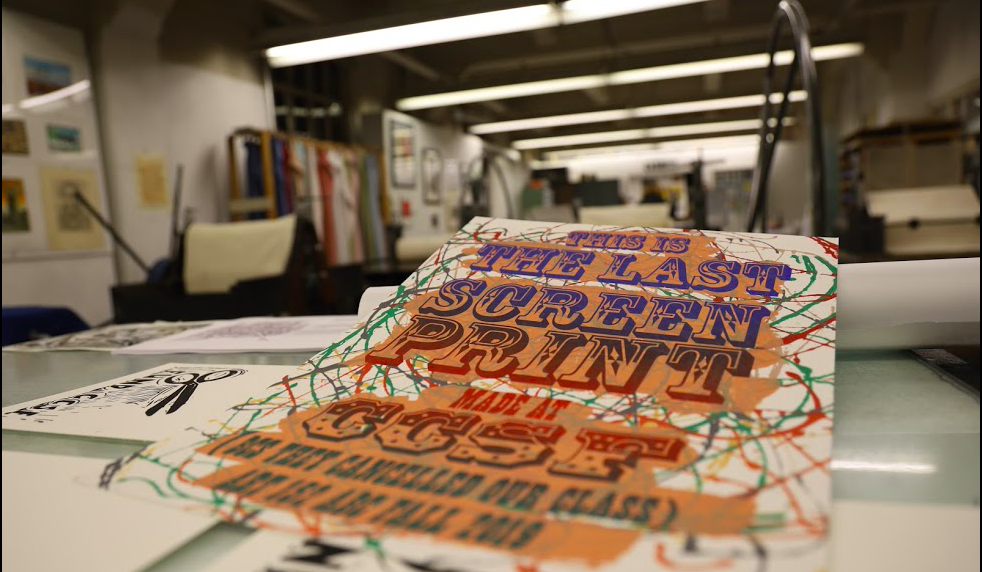

CCSF’s art department quickly responded to class cancellations by putting screen-printing, ceramics, metalworks, and other art media on full display at CCSF’s Fort Mason Center on Dec. 14 in an exhibition protesting the cuts. A screen-printed sign reads, “This is the last screen print at CCSF.”

The art department, offering classes in eight disciplines, is the only affordable art instruction institution in San Francisco, many faculty said, and one that serves multiple sub-communities of the college in numerous ways.

“It is through the arts that people learn about and strengthen their shared humanity,” Art Department Chair Anna Asabedo stated in a letter to the San Francisco Board of Supervisors and CCSF Board of Trustees. “The courses promote creativity, critical thinking and problem solving, the very skills needed to not only navigate and succeed in what are at best restrictive social systems, but to envision and work with confidence towards a humane and equitable world.”

The administration cut 15 art classes. Gone was the metal works and jewelry program, and CCSF’s sole screen-printing class.

Their elimination struck deep for 33-year-old art student Melissa San Miguel.

“CCSF has meant everything to me,” she said.

After working as an education advocate for low-income and foster children for almost a decade, San Miguel tried a summer ceramics class in summer 2017.

“It completely changed my life,” she said. “I found myself connected to myself and my own thoughts in a different way, to a broader community, even in our classroom.”

She was selected as an artist mentee by the New York Foundation for the Arts Immigrant Program in Oakland in 2018. Her classwork earned her internships at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and the Smithsonian American Art Museum.

And those internships gave her insight into how, as an art historian, she could uplift the work of marginalized artists. It’s why she hoped to take Ancient Art and Architecture of Latin America, one of the removed courses.

“I realized that making art, it touched my soul in that through showing my art and sharing my art and learning about other folks’ art, even in the studio classroom, that we could connect as people and connect with each other in an emotional level, intellectual level and talk about things together,” she said.

She’s never been happier, but the elimination of the class disoriented her, she said.

“The cuts are on everybody’s mind these days,” said Marian Keeler, 61, a former architect who received her first career training at CCSF in the 1980s.

She returned about a year ago, hoping to undergo formal training and develop a portfolio.

On one hand, she was driven to enroll by an urge to create and to reflect the currency and urgency of the world, and what people are experiencing, particularly, the national treatment of immigrants, people with differences, white supremacy, and the dismantling of the U.S. democracy, she said.

Separately, it’s one way she connects with beauty.

“For many people this self-expression is something that comes too late in life, as is the case for me,” she said.

The program also fills a void of arts training in public education, metal and jewelry arts professor Jack Da Silva said. A teacher since 1981, he said he’s noticed a downward trend in exposure to art training among students in public schools, a decrease he attributes largely to the time allotted for students to become interested in and study arts.

“I had a 25-year-old student in a 3-D design class I taught a number of years ago — I handed him a 12-inch plastic ruler,” he recalled. “He looked at it, and he asked me, ‘What is this? And why are their numbers on it?’ So sadly, it’s not the first time I had heard such a comment.”

His students create ideas, visualize them, sketch, draw, create templates, make patterns and work with a variety of tools, training their manual dexterity and fine motor skills. Though his program is cut next semester, students’ engagement in the program makes him hopeful it will be reinstated.

“It would be a shame if this doesn’t happen,” he said.

Teachers jobless

Anthony Ryan, a work colleague of Da Silva’s, was another teacher to lose his job in spring. Upon his 2015 hiring, he acquired donated equipment and built furniture to run the department’s sole screen-printing class — work he was happy to do for his students, he said.

“It’s just a waste of all the effort I and my colleagues had put into creating this class,” he said. “The equipment that we acquired and is going to be dormant now, and class is not going to exist anymore.”

Ryan also lost roughly half his income, and the suddenness of the cuts at the end of the semester left him and other teachers unable to plan for a job in spring.

This is because part-timers typically make verbal agreements with their department chairs to forgo employment opportunities at other schools throughout the semester to ensure they can teach all semester. In the art department, 10 part-time instructors lost their assignments, and three lost their benefits, according to art department chair Anna Asabedo.

Altogether, approximately 107 CCSF part-timers were impacted by the Nov. 20 cuts, according to college spokesperson Evette Davis.

“Our faculty have lives, families, hopes, dreams — proven professionals cannot be treated in such a brutally dismissive and expendable manner, subject to abrupt termination and with no safety net,” humanities and interdisciplinary studies professor Georgiou stated in a letter to the college community. How can SF City College call itself a community college when it treats its very faculty so callously?”

Georgiou, a regularly published academic with three graduate degrees related to what he teaches, has taught at the college for 16 consecutive years. His seniority is the highest among part-timers in the Humanities Department. His RateMyProfessors rating is 4.9 out of 5, based on 21 reviews. And he’s never missed a day of instruction, he stated.

“I have no classes left, no health benefits,” he stated. “This cold indifference, (especially to part-time faculty who have given decades of their lives to serving the college), is utterly shameful.”

This is an updated, restructured version of the Dec. 10 article Issue 15 article “Communities devastated after CCSF cuts classes without consultation” published in the Golden Gate Xpress.