The Trump regime’s egregious wrongdoing and pollutive effect on society has wound up bringing greater attention to long-term (yet rapidly worsening) woes of American life like police violence, income inequality, homelessness, and racial bigotry. Whether we’ll finally see lasting positive change in any of those departments is anyone’s guess. But at least the issues are being discussed more widely than ever before.

Several films, both old and new, that arrive on local venues’ streaming platforms this week address aspects of those topics. The most sweeping overview among them is offered by celebrated actress Lee Grant’s 1986 documentary Down and Out in America, which won an Oscar that year despite having been made for HBO. The director, whose acting career was derailed for long years by the Red Scare blacklist (she was married to someone on that list), made progressive social issues key to her choices when she turned to directing. One year before this film, she made another called What Sex Am I? that offered a startlingly ahead-of-its-time take on transgender identity and experience.

Down and Out, whose recently restored print is now part of BAMPFA’s “Watch From Home” programming, covers a startling amount of terrain in just 57 minutes. Its prescience is particularly striking given that the issues it addresses were largely brand-new 35 years ago. While now it may be difficult to imagine an America in which homelessness, sub-living wages, or outsourced jobs weren’t nationwide realities, in 1986 they were largely unprecedented developments. Such ills were among the first gifts of Reaganomics, whose “trickle-up” impact has waged war on the middle class and general US economic well-being ever since.

Grant and her crew roam the nation, interviewing ordinary folk bewildered to find themselves strangled by the system they’d sustained with hard work their whole lives. We start out viewing heartland family farms going under en masse, victims of predatory lending, foreclosures, and forced bankruptcies in what seems a “structured pattern” of seizing mom-and-pop properties for corporate gain. Next there’s consideration of the demise of manufacturing jobs, as companies are given incentives to move their factories overseas, and the work that remains doesn’t pay enough to survive on. Meanwhile, cutbacks in government programs bring a resurgence of hunger and homelessness, two problems America thought it had eradicated since the Great Depression. It’s a very 2020 feeling to watch 1986 footage of shantytowns being bulldozed due to NIMBY political pressure, and signs of communities that prefer jailing the homeless to providing them with the services or housing that might get ‘em off the streets.

Finally, the longest and most wrenching segment spotlights a young couple with several children who until two years earlier had been living in humble (but paradisiacal in retrospect) apartment-block circumstances on the husband’s carpentry work. Then a fire forced them and other residents out. In the film, they’re stuck in a subsidized housing in an NYC hotel without kitchen, private bathroom, or even (frequently) heat or power. Their situation is miserable yet seemingly inescapable, and they’re unable to accept the low-pay jobs available because it would mean losing their public assistance.

Grant’s camera lingers almost unbearably on these two as they break down, admitting they seeing no way out of a situation that’s sucked all the joy out of their lives and marriage, even though they’re still young, industrious, and eager to better themselves.

Down and Out must have seemed shocking at the time. Yet decades later, we’re getting used to the idea that our government truly serves only a limited few, and considers the now-familiar desperation of people whose backs are up against the wall as reasonable collateral damage.

While bigotry has always been a part of American life, the Trump era has turned it into a perverse public virtue, one acted out more visibly every day by his legion followers. It’s particularly refreshing in this climate to drink in a short double-feature by Berkeley’s late, great Les Blank and collaborators that BAMPFA is also offering, starting Wed/22. Made when such celebrations of newly expanding U.S. ethnic minorities were rarely on the radar of white audiences, they remain a concentrated dose of sheer delight.

1976’s hour-long Chulas Fronteras (aka Beautiful Borders) trains Blank’s usual ebullient interest in music, food, and people on Tex-Mex culture, slipping from one side to the other while offering up a full menu of great musicians in performance, including Flaco Jiminez, Lydia Mendoza, Los Alegres del Teran, and more. Even the most cheerful-sounding dance tunes here are not without their sharp political edge in lyrics, however, gradually turning the deceptively breezy film into a regional history that encompasses historical and ongoing prejudice against migrant workers. Trigger warning: Chulas includes brief cockfighting footage. 1979’s half-hour Del mero corazon aka Straight from the Heart, co-directed with Maureen Gosling and Guillermo Hernandez, offers a sort of postscript more exclusively focusing on love songs (and briefly expanding the geographic embrace to San Jose, CA.)

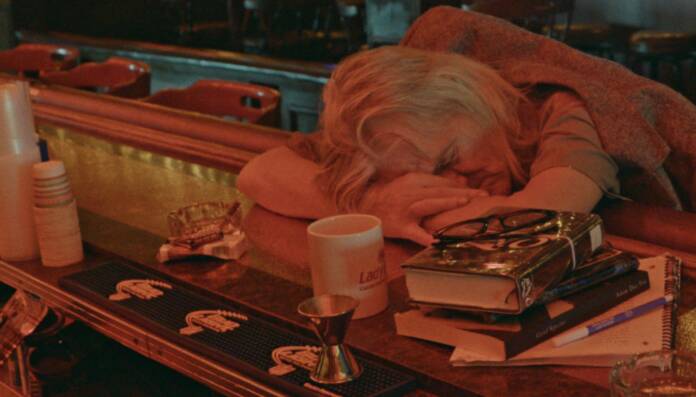

The boozy quick-stepping good times Blank captures have curdled into a permanent-painkiller vibe in Bloody Nose, Empty Pockets, which is accessible via Roxie Virtual Cinema this Fri/24. It chronicles the last day of operations for a Las Vegas bar waaaay off the glittery “Strip” called the Roaring ’20s, as its variously grizzled regulars drift in for a last hurrah. They’re a multiethnic, age-diverse, (mostly) friendly bunch. The difference between this place where “everybody knows your name” and Cheers is that few of these patrons are likely to have particularly comfortable home lives. Some may not have a home at all. It’s late 2016—for people like this, things are only going to get worse.

Visually stimulating like co-directors’ Bill Ross IV and Turner Ross’ prior documentaries (including Tchoupitoulas, Western, and the David Byrne-produced Contemporary Color), this latest feature is nonetheless more of a departure than it initially looks. For one thing, it’s not really nonfiction, despite having been put in the Doc category when it duly premiered at Sundance (which stirred a certain amount of controversy). We’re not really in Vegas; the Roaring 20s was and remains a bar in Terrytown, outside the filmmakers’ native New Orleans. And the “cast” consist of barflies drafted from around the area, plus a professional actor or two. They improvised their own dialogue over several days’ shooting course, most presumably not straying far from their own everyday personalities.

Whether that makes Broken Nose a bold experiment or a deceitful ruse is up to the viewer. But there’s a fundamental truth to its view of social outcasts, marginals, and working-class strugglers who were never much welcomed into the American Dream, but now increasingly find themselves pushed from whatever safe havens they’ve had. One among many ills our political era has exacerbated is that national tendency to identify everyone as either a winner or a loser—with the latter presumed unfit for anything, practically including a right to breathe. This shaggily empathetic ensemble quasi-drama reminds that those on the fast-growing underbelly of society have their humanity, too.