In May and June of 2011, I traveled with my photographer husband to Tunisia and Morocco to document the cultural transformations taking place as the “Arab Spring” unfolded, dictators were toppled, and people throughout the Mediterranean and beyond protested for democracy. On our way, we stopped in Spain to witness the 15-M aka “Los Indignados” Movement that had occupied Madrid’s main square and elsewhere in the country, which like many was suffering from economic collapse, corruption, and massive unemployment. (The 15-M protest movement was directly inspired by San Francisco’s own protest history and iconography.) Soon, the Occupy Movement in the US would seize headlines, but as we observe that movement’s 10th anniversary, it’s good to be reminded that behind Occupy was a global movement for change. You can read more about Occupy and five centuries of protest in my book, Into the Streets: A Young Person’s Visual History of Protest in the United States, now in its second printing from Lerner Books. The story below was originally published to the Bay Guardian’s website on May 25, 2011.

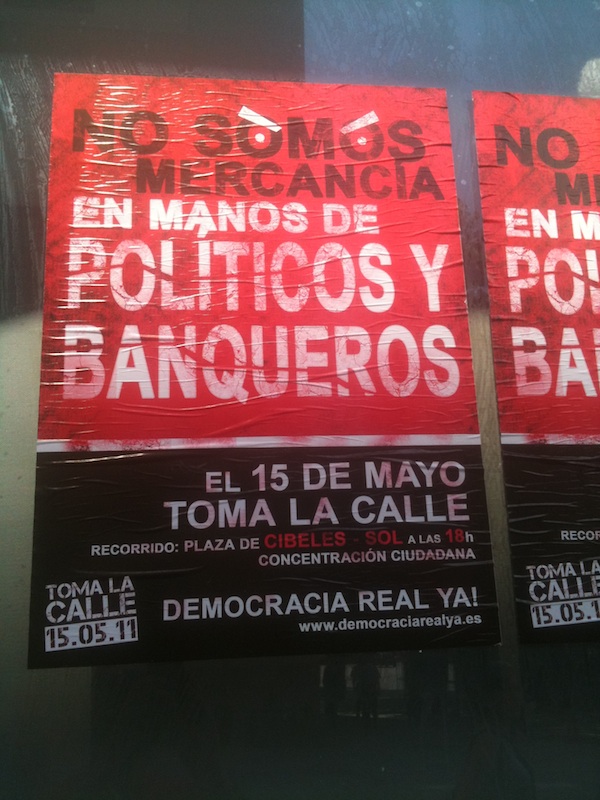

“Yes We Camp,” “Toma la Plaza!,” and “I can haz democracy … for realz now?” signs blanketed Madrid’s enormous Puerta del Sol plaza, as what started as a demonstration by a politically disenchanted few (“los indignados”) on the Sunday before the May 22 regional and municipal elections has grown into a full-fledged, round-the-clock, generalized protest movement, attracting tens of thousands here and in other Spanish city centers.

A calico patchwork of Quechua brand tents and sun-diffusing tarps fans out from the vibrant and loud main speaker/assembly arena, as dozens of perfectly scruffy, mostly half-naked (and from what we saw over two days, mostly white but pretty well-mixed age-wise and gender-wise) people beat the current heatwave while making Sol home. At night, the plaza roils with sympathizers — but a conscious effort to tone down the hard-party aspect without diminishing the festival atmosphere seems to be surprisingly successful.

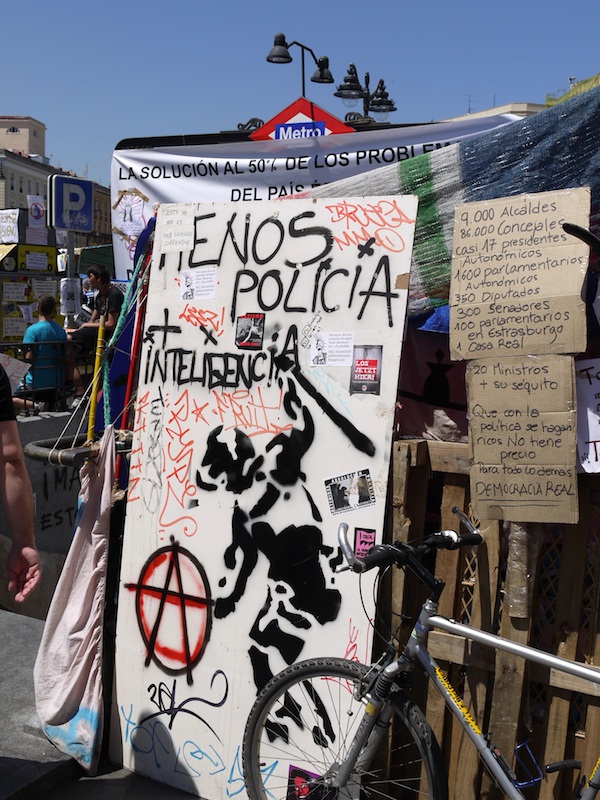

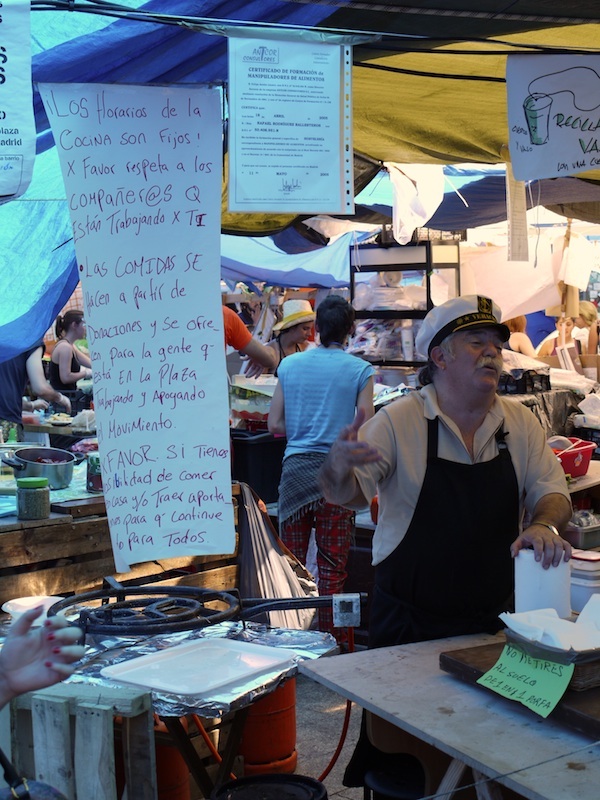

The takeover also transcends the superficial: protestors here in Sol have in effect set up a functional utopian “leaderless” community, with separate committees of volunteers directing communications, sanitation, nourishment (vegetarian options available), feminist representation (“No Photos!” read the banner at the committee’s HQ), language usage, diversity and inclusivity, community outreach, and camp security (the role of which has been broadened under its new name as the “Respect Committee,” Comisión de Respeto).

The only official government reaction to the ongoing demonstrations has been to allow them to continue as long as they stay non-violent. And the current mainstream media narrative is a breathless comparison to the uprisings of the Arab Spring. (More on that below.) On Tuesday, the 24th, we made our way through the “movimiento del Sol,” dubbed the May 15th Movement, or 15-M (www.spanishrevolution.net), to get some idea of what the current protests — or, in the more poetic Spanish term, “manifestationes” — were all about.

BIRTH OF A MOVEMENT

“On the 15th, a group of about 30 of us decided to gather here, it wasn’t too serious, just have a beer or two—and then we were like ‘Let’s stay here!’ ‘Oh, alright.’ Just like that.” Pablo Prieto, spokesperson (portavoz) with the Communications Committee told me. “And from there it was spontaneous, it grew to this point.”

Along the way there was a clash with the police that generated nationwide attention. “On Tuesday morning of the 17th, around 5 or 6am, there were about 200 of us camping in the square, the police came and took us away violently,” Prieto, a wry, intellectual thirtysomething in thick glasses, said. “So after, we met at a certain place, had an assembly, and decided to come back and try again, and it worked. We grew quickly into the thousands. At that point we realized we needed some organization, so we formed the committees and became more of a community. We wanted to form a template so this could be replicated in other cities.”

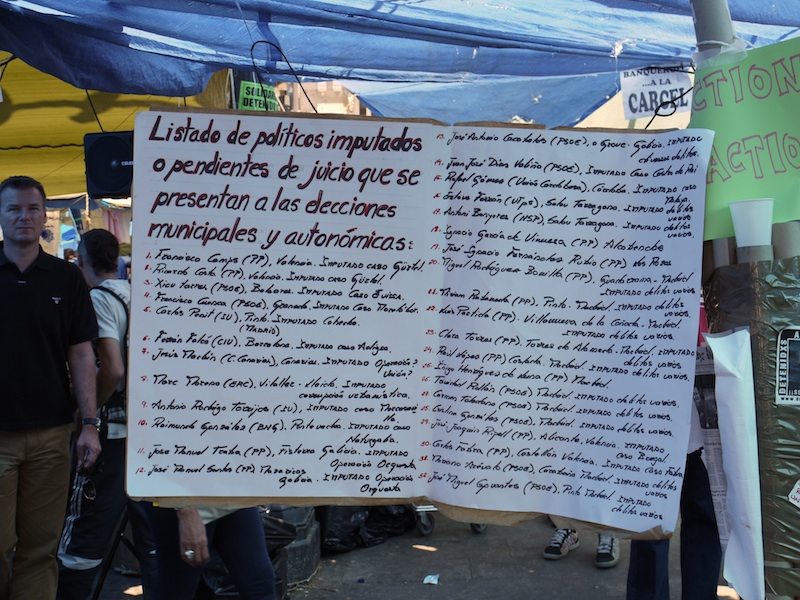

But what exactly is “this”? Spain has been one of the European countries that has been hardest hit by the global recession, and even though it has begun to recover slightly, its unemployment rate, at more than 20 percent total (44 percent among youth), is the highest in Europe. The protests have no official demands yet, but some of the issues that spring to mind are lack of opportunity for educated youth, a wealth of corruption charges within the two major national political parties, a feeling that the European Union and European Central Bank heads are issuing economic directives (like pressuring Zapatero to cut government services) without any democratic recourse, and the new vocal confidence that the Internet gives young people without a corresponding, direct-democratic result in the real world. The May 22 elections slammed the ruling Socialist party, but the protestors have bigger fish to fry.

“In the beginning, the media says that this is mostly about government corruption or only about unemployment,” Prieto said. “But it’s not against the government. It’s against the entire system, the globalized system. And we think we can only fight it with a globalized movement, it’s not just for one particular country. It’s about the global financial system and the deeper roots of the crisis. I realize that sounds a little hopeful, and as a movement right now we don’t have any official goals. Everyone here has issues that they feel should take importance, that they are not being heard enough, and so right now we are just at the stage of everyone getting a voice and using the assembly and direct democracy to find the direction we will take. We are right now in the communications stage, trying to get to one common point, but that is farther than we have felt we’ve been before with the current system.

“I think that is what we’re about,” Prieto continued, “we’re not just protesting against something, we’re proposing an alternative. Everyone has a right to speak, a voice, and everyone has exactly the same power. There’s no leaders, no hierarchy at all, and we believe that’s the way democracy should work. We have continued staying here after the elections — and are planning to stay here through next Sunday, after which we will take our message to other communities — because we aren’t just about this moment. And although the Internet has been crucial to this movement, we need to go beyond that. Once we were in the papers and talking to people we began to reach older people and people with different economic means, people who are offline.” The movement is no mere Facebook page.

ICELAND, NOT ARABIA

Using classic, small-scale anarchist techniques like direct democracy and full-participatory assemblies to overthrow an entrenched global system is a trick not even the best minds or biggest movements have been able to pull off in the past, Internet or no. (And jettisoning representative safeguards against mob rule is probably not very comforting to anyone in a minority. “We realize that this movement is not wholly representative of some sectors of society,” Prieto said, “and that’s why we are making a conscious effort to correct that and to take this into the neighborhoods.”) But the 15-M movement does indeed have some immediate concerns and models, though not the ones you might expect.

We had just come from Tunisia, the source of the “Arab Spring” that saw the overthrow in January of dictator Ben Ali, but where continuing economic woes and pre-election angst had begun to render post-revolutionary hopefulness slightly bitter. Tire-burning protests and Al Qaeda presence had closed off some cities in the south already swamped with refugees from the Libyan war, and gangs of disaffected young men from the Berber hills were setting up random roadblocks out of frustration. In the capital, too, protests continued against the ongoing influence of the old guard in the interim government, even though everyone we talked to glowed with pride and confidence in their newly won autonomy.

So it was curious that papers around the world were heralding 15-M as the Spanish wing of the Arab Spring. Setting up an alternative utopia under a Socialist prime minister is a lot different from risking being shot in the street to overthrow a dictator. There are some commonalities, of course, like high unemployment and a surfeit of young people with no opportunities. Prieto welcomed some of the comparisons, but also balked at being lumped together with the events unfolding to the south and east.

“I think the more complete comparison would be to Iceland,” Prieto said. “We have the energy of the Arab Spring, but we are more like Iceland’s revolution, when they refused to pay back the money or accept the austerity measures imposed by the banks. That was really standing up to power.”

The Iceland connection, a reference to the recent reaction against a complex financial restructuring plan, came up again when I spoke to Manuel Verastegui, an exuberant young man on the Comisión de Respeto security committee, who definitely channeled the positive energy and fervor of the Arab Spring. He came from the nearby city of Rivas, about 15 kilometers away, to live in the plaza.

“Your media probably didn’t cover it, but the protests in Iceland were very influential to us,” he said. “I think that’s what we are taking as inspiration. But that’s just the start. We are tired of being treated like numbers or commodities. The way the present system stands is completely ridiculous. We are given a ‘choice’ of someone to vote for, when each side is horrible. We are told what to do with our money, when why shouldn’t I have a say in how that money is spent? The whole financial system is weighed against the individual.

“For instance, in Spain if you can’t pay for your house, they take your house away from you, but you still owe the money on the house. Why? They want to make sure you can never survive financially, because it is in their best interests. It is the same with jobs. Why is the government getting rid of jobs and services when the rich people are making more money? We have had enough of this, so we are starting our own society here to show what it can be like.”

KEEPING THE PEACE

Verastagui, looking exhausted but still hip in a Jimi Hendrix t-shirt, a constantly buzzing Motorola two-way radio glued to his hand, also gave me some insight on the formation of his Respect Committee. “At first, after the police were violent with us, we decided that we needed a committee of ‘security against the police,’ but then we realized that this was maybe not a good reference. We do not want to answer violence with violence, we have in mind Gandhi and Martin Luther King.

“Also, we began to see that there needed to be some mediation within the camp as well, to help defuse some of the tensions and disagreements — sometimes a small fight — between members. We are all working so hard for this, we are sleeping maybe three or four hours a night. Sometimes these little things get bigger. We try to ensure that no one is disrespectful, and give everyone an opportunity to either work things out, or discuss things in the assembly. We even give out hugs to anyone who asks!”

(As I talked with Verastagui, a vote about organizing a children’s space was ending in the assembly area, and a discussion about establishing a “spirituality committee” was being taken up. An elderly hippie-ish man in vaguely Native American dress was at the microphone saying in English: “We are at the turning point of human history, which is why this movement is happening now. Humanity can go either this way, or that way.”)

I talked more to spokesperson Prieto about the cultural implications of 15-M, explaining that in the United States, anger against the recession had bred not a utopian youth movement but a crochety old Tea Party, and that a protest community like this one forming in Washington D.C. seemed impossible in my mind. “Everyone thought this was impossible in Spain as well, but we don’t care about impossible,” Prieto told me. “Improbable, probably, but never impossible. And yet look what is happening. Our main concentration now is to spread this into all the neighborhoods and suburbs, and then beyond, which is already taking place.

“There are movements like this in every major city in Spain now as well. And one of our biggest inspirations has always been the protest movement of San Francisco. So don’t say it can’t happen again there.”