How much do we take that wee gray focal point at the base of Market Street known as the San Francisco Ferry Building for granted? Many of us commute from its piers via sleek ferries across the bay, hit its farmers’ market for fresh green garlic and a sweet Roli Roti porchetta sandwich, usher our visiting folks beneath its Great Nave for free vendor samples on a rainy day, or, just recently, hike downtown at night to watch fanciful projections swish across the clock tower in an effort to revive the area…

OK, so maybe we don’t exactly take A. Page Brown’s 1893 Beaux Arts waterfront portal for granted, but other than distantly remembering it was once blocked by a hideous double-decker freeway and that it survived both the 1906 and 1989 earthquakes pretty much intact, to many the Ferry Building’s vast and complex history is shrouded in a fog of familiarity: We don’t need to know much about it, only that it will still loom up to greet us where land meets sea.

In his handsome new book Portal: San Francisco’s Ferry Building and the Reinvention of American Cities, Chronicle urban design critic and two-time Pulitzer finalist John King has given us a vivid history of the San Francisco Ferry Building, covering everything from its (disastrous yet enduring) original sunk-timber construction to its weird current position as conservative media avatar of San Francisco’s liberal dystopia. Along the way, we get a 360º view of the legal, labor, architectural, environmental, political, and popular struggles to get the darned thing erected and keep it part of the landscape.

King, of course, tells all this expertly, threading SF’s history through the eye of the Ferry Building needle—while stitching it into the tumultuous architectural tapestries of other big US cities like Boston and New York. I asked him a few juicy questions over email, which he was kind enough to answer. (Check the Events section of his website for upcoming appearances.)

48 HILLS After decades of covering San Francisco’s ever-expanding and -contracting urban project, it makes sense that you would eventually hone in on such a historical (and figurative) focal point as the Ferry Building for a book-length project. You write that the genesis of the idea came when you participated in 2013’s “Unbuilt San Francisco” project. Can you tell me a little bit about your involvement in that, and how it unfolded into this book?

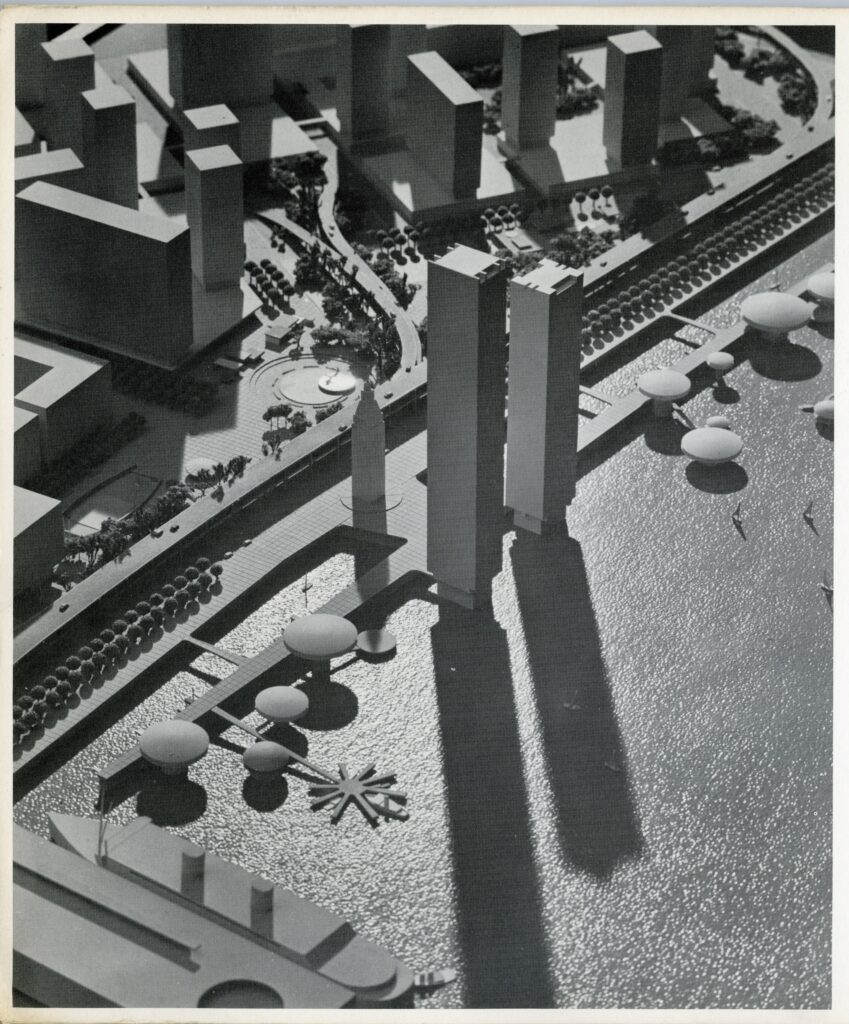

JOHN KING As a history major with a life-long interest in alternate realities—the what-ifs that never came to pass—I’ve been fascinated during my time at The Chronicle in learning about the development proposals and planning schemes that went aground. This fascination often found its way into discussions with other people who care about the city, and we joined together to present a set of exhibits that showed this more widely: I.M. Pei’s scenario for Mission Bay with high-rises along canals, for instance, and Renzo Piano’s quartet of 1,200-foot towers at 1st and Mission streets (Salesforce Tower, by contrast, is 1,070 feet). Or Marincello, the subdivision that would have cloaked the Marin Headlands in tract housing.

Several of the unbuilt concepts were located along the Embarcadero including one proposal to replace the Ferry Building with a nine-block World Trade Center and another to frame it with a pair of larger towers. After the exhibitions closed—the venues were the San Francisco Public Library, SPUR, the College of Environmental Design at UC-Berkeley and the San Francisco chapter of the American Institute of Architects—the weird visions lingered in my head, and served as instigators to explore the terrain in a more exhaustive way.

48 HILLS There’s an undercurrent of poetic reverie around that tall gray clock tower in Portal: What has been your own most memorable encounter with the Ferry Building itself?

JOHN KING My most vivid memory came in 2002, not long before the restored building opened, and a preview dinner was held for local architects and preservationists. As all these people who had fretted about or lusted after the battered landmark walked in to see the results of the transformation, you could sense a collective gasp at the simultaneous turning back of the clock, and the creation of a space ready to embrace the century ahead.

48 HILLS While Portal is told pretty much as a straightforward, chronological tale of the building’s construction, use, and significance, you conjure so many other histories swirling around it, including those of the great migrations that shaped the city from the beginning, labor’s travails to organize and protect workers throughout the waterfront’s development, the omnipresent influence of big business on the city’s politics, the epic legal battles of city “settlement,” the continual struggle against economic inequality, and the often terrible, sometime very successful story of urban development/redevelopment in the US.

Two struck me, especially. The first is the role of community voices—ebbing, flowing, overruled, overwhelming—in the history of the building. Sometimes the populace is deliberately courted though advisory boards and ballot initiatives, sometimes it’s literally railroaded into accepting massive changes by government/big business fiat. I think this history gives tremendous context to our contemporary “conversations” over local control, CEQA/EIRs, upzoning, and other community development impacts. What lessons, if you see any concrete ones, does the Ferry Building hold in these debates today?

JOHN KING There’s so much complexity in the saga of a city, and that’s part of what attracted me to writing a book about the Ferry Building—today’s icon offers a constant to gauge the churning impact of 20th Century life on San Francisco, from transportation modes to globalization and the tension between long-range planning and short-term development desires. I believe we need more holistic and equitable planning; at the same time, I’m wary of the assumption that the more controls and hurdles placed on planning efforts, the better.

The Ferry Building shows us that patience can be a good thing in a city, rather than hooking a city’s future to any bigger-is-better development notion that comes along. But it also shows us that substantial changes are not to be feared, and as the city grapples over the challenge of preparing for sea level rise in coming decades, everyone’s preconceived notions are going to be put to the test.

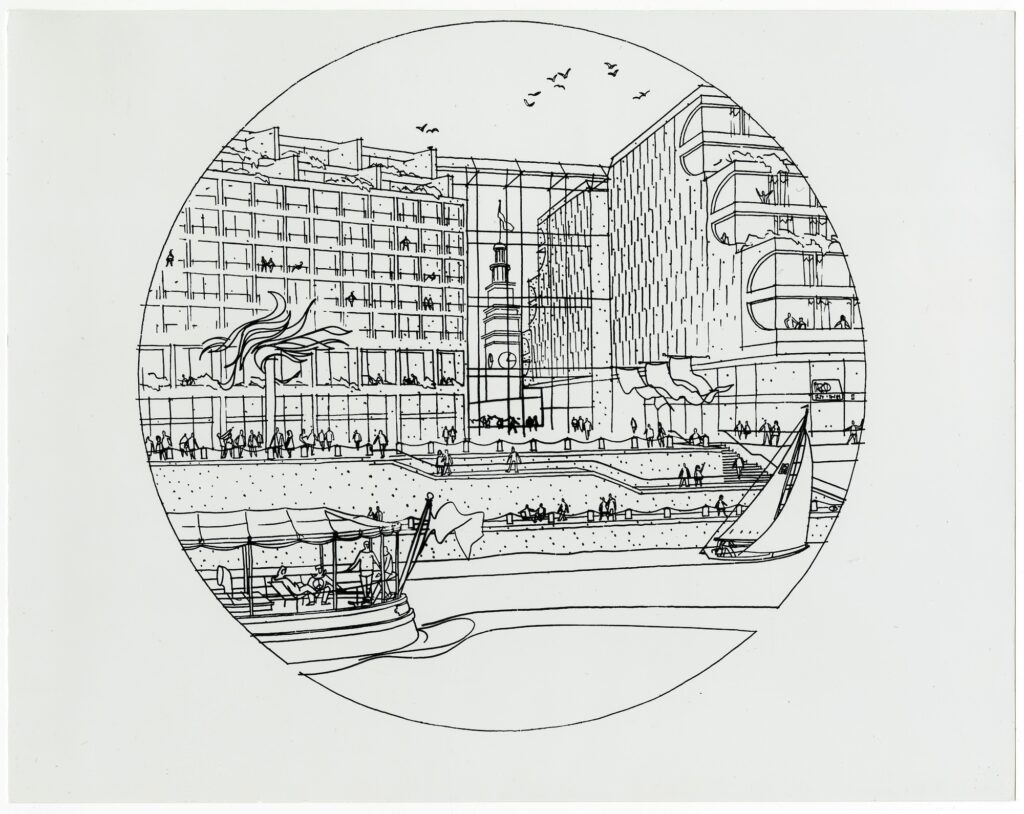

48 HILLS The second theme that struck me is the tremendous alternate architectural timelines that you unearth. I loved reading about the many changes proposed to the beloved, if rather plain, original design executed by Arthur Page Brown that range from the weird and dated—a giant 1970s fern bar (presumably to be very gay), a huge glass mall-like atrium virtually enclosing the tower, that retro-sci-fi-esque scheme featuring floating office towers—to wild AG Rizzoli-adjacent fantasias, like one that would have transformed the building into a sprawling neo-classical (and a bit fascist-looking) octopus with a “useless dome.”

Along the way we get rejected redesigns by greats like IM Pei, which helped inspire you to write the book. Were there any alternative timeline designs you wish had been enacted, even if you could just see what they would have looked like?

JOHN KING Not really! San Francisco dodged a lot of bullets along the Embarcadero. I certainly wouldn’t want to be staring at a Ferry Building with the clocktower standing but the two long wings lopped off, an idea championed by the likes of landscape architecture legend Lawrence Halprin in the early 1960s.

But if had to choose one? Perhaps Ferry Port Plaza, a project that would have replaced piers 1 through 7 in 1969 with a 17-acre mega-pier stretching 1,300 feet into the bay, a wide public promenade girdling a 10-story hotel and eight stories of commercial space, the two horizontal blocks linked by a glass atrium.

Do I wish it had been built? Not at all. But it was very much in keeping with “advanced” shoreline planning of the era, and there’s a bit of me that’s curious about how it would have stood the test of time.

48 HILLS I came to San Francisco in 1994—my first Pride celebration uniquely took place along the Embarcadero (the Civic Center was being refurbished), on a tremendously sunny day on the green lawn in the ghost shadow of the Embarcadero Freeway. When older gays told me there had once been a double-decker concrete monstrosity blocking the magnificent tower, I was flabbergasted … You tell the Embarcadero Freeway tale so expertly, it re-fired me up to want to take down several other freeways. What other huge opportunities to reveal civic gems (due to car culture or simple bad planning) are we missing?

JOHN KING That’s a great question, and one that other people have posed to me since the release of the book. It’s also tough, given all the complexities. So how about this? Find a way to fulfill the dream of Art Agnos when he was mayor and somehow thread the Embarcadero roadway beneath the spot where Market Street should meet the Ferry Building. Then, turn the disconnected cluster of public plazas into a single grand lively place.

48 HILLS Finally, OK, while I am certainly glad that it’s not named The A. Page Brown Entrypoint, I have always disliked the name “Ferry Building” as it is so very plain for such an important landmark. Do you feel the same? If so, any alternative suggestions?

JOHN KING Nope! Strip away all the architectural ambitions and civic aspirations, and the structure initially dubbed the Union Depot and Ferry House was intended to serve as a transit hub. There are worse sins than understatement; “Ferry Building” keeps things simple and real.

You can purchase Portal here and at local bookstores.