Arriving shortly are two film festivals focused on our problematic present and hopefully sustainable future: There’s the eco-centric International Ocean Festival, running this Fri/12-Sun/14 at Fort Mason’s Cowell Theater, then April 15-22 online; and next Mon/15 through Sun/21 the SF Urban Film Festival, offering a range of screenings, panel discussions and more on community planning/history at various SF venues.

But a third annual event also on the immediate calendar is entirely dedicated to the past—one receding so quickly that soon the entire era it enshrines will have ended over a century ago. Naturally we’re talking about the San Francisco Silent Film Festival (www.silentfilm.org), whose 27th edition runs this Wed/10 through Sun/14. There’s a big difference this year: The Castro Theater’s long-term closure for extensive remodeling means that the festival has had to move, to the Palace of Fine Arts in the Marina. That means a loss of over 400 seats (the Palace has a capacity of 960, versus the Castro’s prior 1400), so you may want to arrive earlier than before for shows bound to be particularly popular.

Otherwise, at a glance SFSFF’s 2024 program looks a lot like 2023’s, in that it starts with Douglas Fairbanks and also features showcases for Buster Keaton, Laurel & Hardy, Edward Everett Horton, German star Brigitte Helm, directors Allan Dwan and Yasujiro Ozu, plus an “olde dark house” comedy thriller. But of course these are all different films, some of them classics that may be familiar, many others likely to be fresh discoveries.

As usual, the program includes some titles you couldn’t possibly have seen before, at least in such prime condition, as they’ve been recently rediscovered and/or restored. That includes The Pill Pounder, a 1923 short featuring pre-stardom flapper luminary Clara Bow—a film long thought lost, and whose screening will be its first in 101 years. It will play Thursday afternoon with another world-premiere restoration, of 1926’s Dancing Mothers. Though billed below her co-stars, this was the breakthrough role for the effervescent Bow, whose society wild child provides an ebullient contrast to all the high-minded dramatics around her. She’d soon be not only Paramount’s top attraction for the next several years, she’d inspire a series of pop culture homages from cartoon bombshell Betty Boop to songs by Prince and Taylor Swift.

Bow famously had “It”—the era’s coy euphemism for sex appeal—and so did several other stars restored to the silver screen at Silent Fest. Actually, that screen isn’t silver (or B&W) but rather a vivid range of rich earth tones in The Black Pirate, which opens the program on Wednesday night. Fairbanks is in reliably athletic, charismatic form as the sole survivor of a ruthless pirate attack who manages to infiltrate the marauders’ own criminal ranks to wreak his revenge. This newly restored period spectacle was just the third feature to be shot in two-tone Technicolor, and perhaps the logistical difficulties imposed by that process explain why it’s more of a straight suspense drama (albeit with plenty of action) than the star’s usual freewheeling, good-humored romps. Those fond of such swashbucklery will also want to go the following evening to Frank Lloyd’s 1924 The Sea Hawk, an elaborate intrigue set in Elizabethan times, drawn from a novel by the author of Captain Blood and Scaramouche.

There is also hefty hunk value in Dwan’s 1927 East Side, West Side, with George O’Brien as an orphaned wharf rat who becomes a champion boxer after being taken in by a Jewish family. Off-screen, the star (known as “The Chest” for his impressive physique) was the son of San Francisco’s Chief of Police, as well as a former boxer and future John Ford regular. He’s as handsome as he is scrappy in this buoyant melodrama; ditto the NYC location shooting.

A lesser-remembered leading man (as well as a prolific director) worth rediscovering is Englishman Henry Edwards, who stars in German director Georg Jacoby’s 1928 Danish production The Joker. It has him as a titular good guy (not to be confused with Batman’s nemesis) who comes to the rescue of two sisters being preyed upon by blackmailers. The combination of soapy melodrama and visual extravagance is comparable to von Sternberg, with Edwards providing an appealingly empathetic element.

Unafraid to stir comparatively little sympathy is Metropolis’ Helm, whose 1928 vehicle The Devious Path has her as a beauteous but shallow, impulsive young wife to a rich lawyer, whose mild neglect drives her to “dens of iniquity.” There’s some pretty strong content (including suggested heroin use) in this impressively mounted tale, directed by G.W. Pabst right before his celebrated duo with Louise Brooks, Pandora’s Box and Diary of a Lost Girl.

Other resurrected luminaries of the period on display include Norma Talmadge, doing some dramatic heavy lifting as beleaguered “Polly Pearl” in Frank Borzage’s Stella Dallas-like 1925 tearjerker The Lady; and Syd Chaplin (yes, Charlie’s brother), whose cross-dressing comedic specialty propels the following year’s farce Oh! What a Nurse! Gaston Glass, whose acting career quickly shrank to bit parts with the “talkies,” had a brief spell in the silent limelight. He’s the male ingenue in James Cruze’s 1928 The Red Mark, a newly restored meller unusually set on a convict-colony island, and also among many potential murder victims and/or suspects in the ensemble for Alfred Santell’s 1927 The Gorilla. That mystery was one of many stylish Olde Dark House comedy-thrillers that flourished in the late silent and early sound era.

Also more of an ensemble piece than a star vehicle is Hell’s Heroes, not the first or last screen version of the novel Three Godfathers by S.F. native Peter B. Kyne. But nearly all the other versions of this tale—about Wild West outlaws who turn over a new leaf upon getting stuck with the infant child of a dying frontierswoman—are more maudlin than William Wyler’s, which was shot in the Mohave Desert for extra realism. Made in both silent and talkie versions (because many theaters hadn’t yet converted to sound yet), it was a surprise hit in 1930, and remains one of the best western dramas ever made.

Of course there’s plenty of international fare on this year’s schedule, including several well-established classics. Like Wyler, Japanese master Ozu was just at the beginning of a very long career when he made the antic childhood portrait I Was Born, But… in 1932. (The silent era extended considerably later in some countries than it did in the U.S.) Benjamin Christiansen’s extraordinary 1922 Haxan aka Witchcraft Through the Ages is a quasi-documentary charting the history of European superstitions that really does not stint on the lurid fantasy depictions. Equally fanciful is 1921’s Swedish The Phantom Carriage, whose director Victor Sjostrom continued in movies as a celebrated actor after he quit creating them. Using intricately layered double-exposure images to convey a spirit world lurking within our everyday one, this allegory proved a lasting influence on filmmakers from Bergman (who cast Sjostrom 36 years later in Wild Strawberries) to Kubrick.

By contrast, sober realism is the tenor struck by two foreign features likely to be new to most Silent Fest viewers. Karl Grune’s 1923 The Street may sport a degree of high German Expressionism in its stylized cityscape, entirely built on soundstages. Still, it anticipates neorealism in its story of a middle-aged drudge who storms out on his wife, intent on finding some excitement. He finds a little too much of that, involving con artists, loose women, pricey nightclubs and even murder. While the melodramatic plot is no great shakes, the highly accomplished production shows German studio craftsmanship at its peak—and there’s Nosferatu’s Max Schreck in a supporting role as a bonus. Julien Duvivier’s Poil de Carotte aka Carrot Top was the first among several screen adaptations of Jules Renard’s 1894 novella. Its redheaded boy hero remains irrepressible despite the myriad cruelties visited upon him in a Dickensian childhood.

When silent cinema began to be appreciated anew in the 1950s, after at least a quarter century’s complete neglect, many imagined it had consisted of very little beyond slapstick—since that was the material that worked best for new audiences watching on TV or in revival houses. Now of course we know the medium achieved great range and sophistication of expression in the pre-sound era.

However, fear not: This year’s SF Silent Fest has plenty of yoks in its program, though I’m pretty sure no pies are thrown. There’s the return of Edward Everett Horton, whose silent career as a star comedian (later he’d be an instantly recognizable supporting character and voice actor) was resurrected in a prior shorts program; this time he’s embroiled in the feature-length hijinks of 1926’s Poker Faces. Laurel & Hardy are also back, with three two-reelers that run a gamut of wanton destruction: Your Darn Tootin culminates in a mass street corner depantsing; Two Tars turns a traffic pileup into an orgy of vehicular harm; while The Finishing Touch has the duo as construction workers, who needless to say manage only to deconstruct.

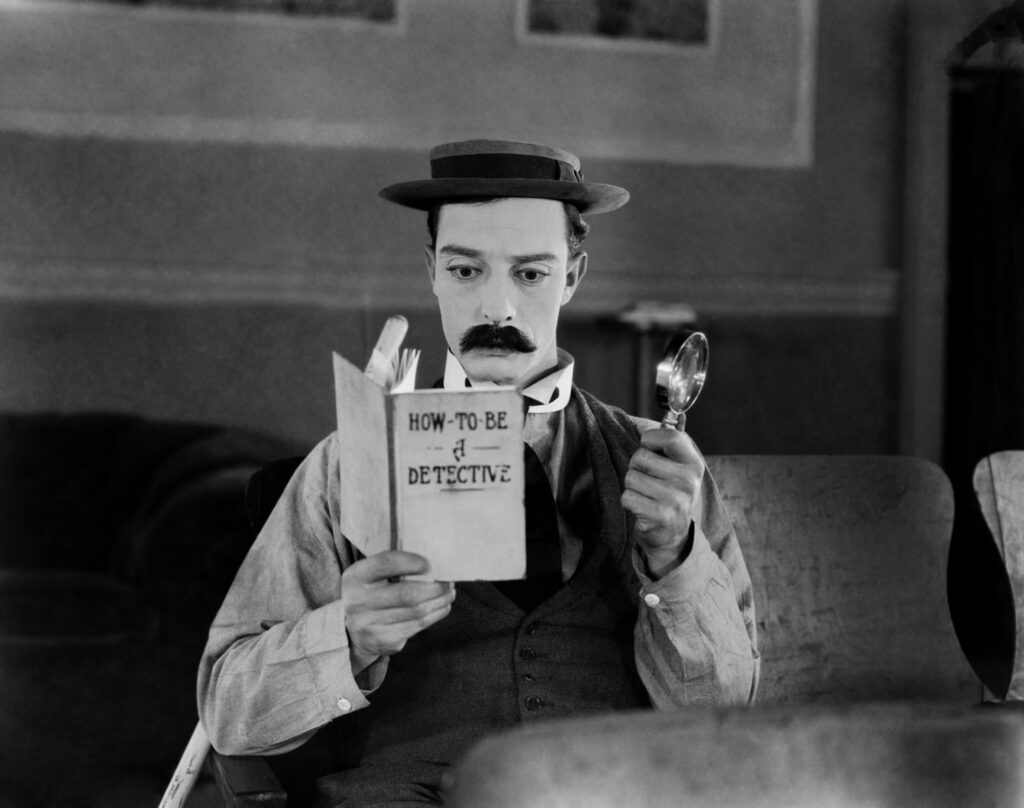

Two of the epoch’s greatest comedic talents are showcased in what you could argue (at least I would) are their greatest vehicles. There’s Harold Lloyd with 1927’s The Kid Brother, a rural underdog tale that is very funny, but also has a little more narrative heft and depth than he usually bothered with. Some corny intertitles aside, it’s just about perfect. Yet in a class of its own is Buster Keaton’s 1924 Sherlock Jr., perhaps the ultimate proof of his ingeniousness—its lovelorn hero, a projectionist, falls asleep and imagines himself walking into the movie his theater is showing. (That idea obviously inspired Woody Allen’s much later The Purple Rose of Cairo, and a climactic chase also clearly provided a model for Bogdanovich’s What’s Up, Doc?)

The surreal gags that ensue are sheer brilliance. But providing early proof that screen comedy can be too smart for the masses, this dazzling film was a flop—critics and audiences alike found it too complicated to be humorous. Disastrous preview screenings are a reason why it is so short, at just 45 minutes; Keaton kept cutting in pursuit of better results. (It’s painful to imagine how much celluloid gold wound up edited out, then nonchalantly destroyed.) It will be shown with Keaton’s first solo directorial effort from four years earlier, the short One Week, which in its way is an equally flabbergasting—not to mention hilarious—assembly of intricate, seemingly impossible gags.

You might not expect any mix of wartime deprivation, socialist propaganda and knockabout farce (plus a camel) to work at all, let alone be as funny as those Hollywood titans at their best. Nonetheless, such is the case with Nikolai Shpikovsky’s 1929 The Opportunist, an inspired spoof set in Ukraine several years prior, during the Civil War between Bolsheviks and the White Army. Trying to make a buck amidst that chaos, punctuated by the occasional bomb, is a schlemiel-type antihero (Ivan Sadovskiy) as shameless as he is hapless in his attempted capitalistic entrepreneurialism. For all the laughs achieved, the film manages to land on a celebratory closing note of harvest threshing—agriculture being the passionate-clinch ending of classic Soviet cinema.

As ever, each show at Silent Fest will have its own live musical accompaniment, with this year’s performers ranging from solo pianists, organists and multi-instrumentalists to the Monto Alto Motion Picture Orchestra, Guenter Buchwald Quartet and Matti Bye Ensemble.

The 2024 San Francisco Silent Film Festival runs this Wed/10 through Sun/14 at the Palace of Fine Arts Theater in SF. For full program, ticket and schedule info, go to www.silentfilm.org