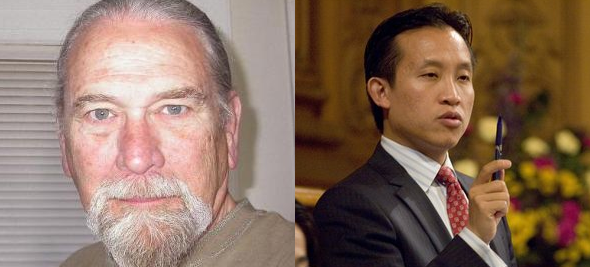

Calvin Welch (left) and Sup. David Chiu have very different approaches to dealing with Airbnb.

By Tim Redmond

MAY 1, 2014– It’s pretty clear that San Francisco is (finally) going to get around to regulating short-term Airbnb-style rentals this year, but two different approaches – one by Sup. David Chiu and the other by some longtime housing and neighborhood activists – raise a key question:

Can we ever properly regulate and enforce a practice that amounts to a wholesale rezoning of the city’s residential areas – or should we try to strictly limit or shut down Airbnb rentals?

And if we’re going to allow the practice of turning rental units all over town into part-time hotel rooms, how should we enforce the law to make sure that (like so much else in housing regulations) it’s not ignored or abused?

I’ll add one more question: Can we just ignore the fact that some of these companies have been ducking taxes and running a business model based on illegal activity for years – and just grant them complete amnesty going forward? Should Airbnb be able to utterly avoid liability for the problems it has created in the city?

Chiu has been working with airbnb and with some tenant and landlord representatives for months to come up with a plan that would allow San Francisco homeowners, landlords, and tenants to rent out their units as hotel rooms – and would set some limits to prevent what’s happening now.

And what’s happening now is ugly.

There are, as of today, some 5,700 airbnb listings in San Francisco. Some of those are, of course, homeowners who are sharing their place while they’re out of town. Some are tenants trying to pick up some extra money. Many are landlords who may have evicted tenants under the Ellis Act, or who are just keeping units vacant, and using them as hotel rooms.

Why not? You can make, according to a study by the Tenants Union, as much as $100,000 a year renting prime apartments in nice neighborhoods as hotel rooms. Real hotels, which hire union employees and get permits, make perhaps half of that per room.

The problem is that it’s all illegal. Airbnb and VRBO (Vacation Rentals By Owner) require users to violate local zoning laws, which largely forbid hotels in residential areas.

So what do we do now? The Airbnb rentals are all over the city. It’s spreading. It’s illegal now, but it’s almost impossible to enforce. So, just as he did with in-law units, Chiu is looking for a way to bring the game out of the shadows – and in the process, collect some tax money.

But there’s an essential difference between in-law units and Airbnb. In-laws create more housing; Airbnb takes housing out of the market. More in-laws might possible provide some cheaper apartments; Airbnb drives up the cost of housing all over the city.

Which is why Calvin Welch, Dale Carlson, and Doug Engmann – all of whom have been involved in community politics for decades – are talking about a ballot initiative that would pretty much shut the game down.

We’re talking two different approaches here, and it’s important to understand what’s at stake.

Under Chiu’s measure, property owners and renters could use Airbnb or VRBO or other similar sites to rent out their principal residence – that is, you can buy a condo or a building and just rent out the units as hotel rooms. You’d have to live there 75 percent of the time.

One reason Ted Gullicksen, director of the Tenants Union, generally supports the measure is that it prevents landlords from using these unauthorized sublets as a cause for immediate eviction. Nearly every residential lease or rental agreement in the city bans subletting, and tenants who turn their apartments into Airbnb rooms can get tossed out.

Under the Chiu bill, the first time someone’s caught doing that, the only remedy a landlord can use is to give a 30-day notice to stop subletting. That is, use Airbnb, violate the lease – and you get a second chance. Nothing says that the landlord can’t evict on a second offense.

Gullicksen told me that he’s not opposed to the Welch initiative, and that “both of them need some work.” He wants stronger tenant protections in Chiu’s legislation, and clear language exempting below-market-rate housing, SROs, and public housing. He wants Welch to add similar tenant protections in his measure.

But, he said, the notion of a little bit of Airbnb is acceptable: “We thought it was okay to allow limited use of your own place.”

And let’s face it: There are tenants who are part of this “sharing economy” game. Some of the worst offenders are big landlords and speculators, who have discovered that there’s more money to be made with hotel rooms than traditional rentals. But it’s happening all over the city.

There’s no question that Airbnb was, and is, a part of the discussion here. I went to the Ethics Commission website and counted 39 visits in the past year between Airbnb lobbyists and Chiu. (The lobbying team, headed by Alex Tourk, is pulling down $37,500 a quarter, the records show.)

Airbnb has agreed to start collecting the hotel taxes that it owes the city – this summer. Nothing in the Chiu legislation would require that the company pay its back taxes.

What Chiu is proposing is much milder than what the attorney general of New York State is doing. Eric T. Schneiderman says all of the Airbnb listings are illegal. Chiu’s aide, Judson True, told me that the legislation looks only forward, not back.

But there’s more to the Chiu ordinance than simply legalizing short-term rentals. It essentially rezones the entire city, allowing commercial activity – that is, hotel rooms – in every single neighborhood. It also follows the same path as the Google Bus Project – you let someone set up a business model that only works if its contractors break the law, then you convince the city to look the other way, then you go back later and say: hey, it’s been happening so long now that you can’t just shut it down.

“We asked Chiu if he would be willing to back away from changes to the Planning Code that redefine “residence,” and he said that wasn’t something under discussion,” Welch told me.

The proposed initiative would require anyone who wants to create short-term rentals to register first with the city and to certify that the use doesn’t violate any local or state laws. If the person renting the unit is a tenant, he or she would have to prove that the landlord accepts short-term subletting. Each short-term rental unit would need $150,000 insurance.

If the Chiu ordinance passes, the initiative wouldn’t technically shut down all Airbnb rentals – but it would make the process more transparent and difficult. If Chiu’s bill fails – and I think it’s going to be a close call – then the initiative would pretty strictly limit Airbnb rentals in the city.

Now: If we outlaw all of this, Gullicksen said, it’s still going to happen, and the city will have to enforce the laws equally – including going after tenants. “We don’t want the city attorney to start suing tenants who are just renting out their rooms while they’re in New York for a week,” he said.

But all of that ignored the real culprit here: A $10 billion corporation that is making money by making the housing crisis in San Francisco worse, has cheated the city out of millions in tax money – and that can’t exist without illegal sublets.

Before Airbnb, there were a few people in the city who used, say, Craiglist to sublet their places now and then when they were out of town. It wasn’t a big deal, it wasn’t a huge issue, and there was no reason for a crackdown. But when Ron Conway and other venture capitalists got into the game, it became a growth issue. Airbnb needs lots of illegal sublets, thousands and thousands, and more every month, to keep its valuation up so its investors can cash in when the outfit goes public. I’m not sure that just a little Airbnb works.

And remember: The entire business model is based on encouraging people to violate the law. The growth that has made the early investors very rich (on paper) is based on convincing renters to put their tenancies at risk (and then give them no help when they get in trouble) and homeowners to violate city zoning codes (and will Airbnb “share” the fine? Um, no.)

If some tenant falls for the Airbnb pitch, and fails to read the “terms of use” (does anybody on any website read that fine print? Seriously?) and winds up getting an eviction notice, it’s all the tenant’s fault. Airbnb doesn’t get evicted, or hold any liability at all.

This is what bothers me most about the whole thing. Some tenants are making a little money by renting out their places under Airbnb. Some landlords are making a lot of money doing it. But nobody’s becoming a billionaire that way – except Airbnb. And no matter what happens to the tenants and homeowners, Airbnb walks away unscathed.

It’s like the illegal cab companies, Uber and Lyft: Until the regulators forced the issue, they wanted the drivers to take all the responsibility for insurance coverage. Drive a Lyft taxi, get in an accident, and injure someone? Not the fault of the company that put you in the car and offered you a way to make money driving passengers. No; it’s all on you. Thanks, “sharing economy” – the brokers make the millions, and the users take all the risk. Put another way: Airbnb and Lyft share your profits, but don’t share your liability.

The Chiu legislation does nothing to put any further onus on Airbnb, except that the company has to collect taxes (in the future). The initiative, on the other hand, makes the “broker” – Airbnb – liable for violations of the law, too, just like the tenant or homeowner.

Now: It’s unusual for Gullicksen and the Tenants Union to be supporting a piece of legislation that Welch and other housing advocates oppose. And Gullicksen told me that there’s “certainly an argument” for what the initiative would do. This is all in the context of a bunch of measures headed to the November ballot – including an anti-speculation tax, which everyone in the tenant and housing world supports.

Would a ballot battle over Airbnb make it harder to pass that tax? Or would an initiative that will get a lot of support from the West Side of town, where people who don’t normally vote with the left are freaked out by Airbnb, actually help?

Tricky. But these folks are used to working together under challenging circumstances – the left in San Francisco is often a bit fractured, but we generally seem to work it out in the end. I don’t know what that looks like here, but I don’t think a measure that lets Airbnb reap most of the rewards while the rest of the city gets the liability is going to work.