Iris Canada, 100, sat in a wheelchair looking frail and tired but not without the touch of her impeccable sense of style; yellow blazer, a sleek ebony wig paired with silver earrings. As she sat in front of banners protesting her impending eviction, Canada smiled and spoke gently as she occasionally broke into prayer for her former landlord Peter Owens.

“I was born in 1916, the same year the 19th Amendment gave women the right to vote. When I was 13 the stock market crashed. At 25 I cried with my country when Pearl Harbor was bombed and I celebrated with my country when the war ended. I was 38 when Brown v. Board of Education ended segregation in American schools,” Canada said, “When I was 74 and had been collecting Social Security for 10 years, the US was fighting the Gulf War. I was so proud that I voted to elect our first African-American president after my 92nd birthday.”

Despite successfully delaying her eviction a dozen times, she knew she wouldn’t be able to survive the loss of her home. Canada was a strong, determined woman who took pride in the life she had built and sought to fight to stay till her dying breath.

“This is killing me. This home is all I have, this is where I want to live and this is where I want to stay,” she said. The two-bedroom Western Addition residence had been Canada’s home since the 1950s (accounts vary). Canada, who worked as a beautician and a nurse, moved to California from Texas in the 1940s with her husband.

“My husband built the furniture in this home. This place is full of his artwork and furniture we bought together,” said Canada.

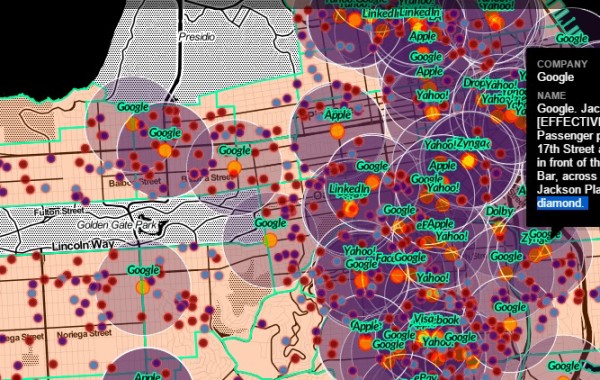

It’s no secret that the cost of living in San Francisco is insanely high. By several metrics, the city has the priciest real-estate in the country, highest rent and worst income inequality in the state making it among the ten least affordable cities in the world. These trends have been forcing low-income residents to leave, and it’s the stories of longtime residents of color that most boldly narrate the story of the city by the Bay that has rapidly gentrified.

Canada’s story struck a chord with housing activists who have witnessed similar instances of seniors being evicted. Tommi Avicolli Mecca, a staffer with the Housing Rights Committee, has spent the past two years fighting tooth and nail for Canada to stay. He’s been at every protest, every court hearing, and every eviction scare that Canada was put through before she was ultimately evicted last month.

“This is a city of artists, of writers, or thinkers, this is a city of the working class that was known for its acceptance and compassion but just look at how we treat our elderly. Is this the San Francisco you want?,” Mecca spoke to an audience gathered outside the Courthouse. The crowd chanted back a unanimous “No,” Mecca maneuvered in and out of the courthouse all the while fielding calls to get updates on Canada’s deteriorating health. “I have seen this before, we have all seen this before. She will not survive this it is killing her,” said Mecca before disappearing to the courthouse again.

The owners of the unit — Carolyn Radisch, her husband Peter Owens, and his brother Stephen Owens who bought the property in 2002 — have a different story to tell. They claim they tried their best for over a decade to accommodate Canada.

At the time the Owens family bought the building they issued Ellis Act eviction notices to all the residents as they planned to turn the building into Tenancy in Common units.

Canada was given a so-called “life estate” designed to let her remain in the apartment for a fixed rental agreement of $700 a month until she died. The non-traditional agreement that was carved out after Canada’s then-attorney convinced Owens that it would be hard – and cruel – to force an elderly Canada out.

In 2015, Owens asked Canada to sign a document that would allow him to convert the building to condominiums. Canada refused to sign the application after talking to her lawyers who advised that she would, in essence, be giving up her “life estate.”

Owens alleges that Canada was no longer living in her apartment, and in court the lawyers presented evidence alleging that the apartment was in bad shape and had been abandoned as Canada was living in Oakland with her caretaker niece, Iris Merriouns. The Owens family argued through their lawyers that since Canada “permanently resided” with her niece she violated the so-called life estate agreement hence demanding she should be evicted.

Canada’s niece Iris Merriouns has consistently disputed these claims: “It’s ridiculous. Peter has taken advantage of the fact that my Aunt has been sick and has had to deal with family tragedy,” she said. Merriouns cited Canada’s health, travel to stay with family and a dying niece as reasons for Canada’s absence from the apartment for long periods of time.

The two-bedroom apartment was full of Canada’s belongings. Mark Chenerv, Owens family lawyers, alleges Canada hadn’t lived in the apartment for over two years. Instead, he blamed Merriouns as exploiting her aunt’s health and old age “for her own greed… what you see here is the exploitation of Ms. Canada by her family. My client Mr. Owens has been more than helpful to Ms. Canada. From making sure her food from meals on wheels is delivered to her to ensuring that she’s comfortable. We’ve done everything we can,” Chernev told 48hills after yet another court hearing in August of last year.

In a heated argument between Chernev and Canada’s attorney Dennis Zaragoza in the corridors of the courtroom in August, Chernev went on to allege that the Owens family were ready to accommodate all demands: “My client has told you he’s ready to give you anything in writing, anything you want you can have it all he wants is for your client to sign the conversion papers. Instead, her niece (Merriouns) wants to buy the condo at a discount price. Tell me how a 100-year old woman on social welfare is going to buy the apartment?” he said.

Chernev told this reporter that his client was willing to let Canada stay for the rest of her life if she signed the condo conversion papers — a claim Canada’s lawyer Zaragoza and niece Merriouns refused to believe. “Signing off the conversion papers means she would lose her right to stay. What is to stop them from using another excuse to try and evict her afterwards,” Zaragova said.

Canada wasn’t present at the court hearing, neither was she seen at subsequent protests, as she battled her worsening health. Those who knew Canada or heard her speak pleaded she be allowed to stay until she had passed and considered her a living history of San Francisco. Whenever she made an appearance Canada spoke about the changing neighborhoods, the Fillmore district not far from where she lived was once called the “Harlem of the West” has become unaffordable to many African-American families that once inhabited it.

When Canada first moved she was surrounded by a large bloc of extended family members. The neighborhood now known as Hayes Valley was once a harbor for African-American families looking for a decent life. Canada’s building was owned by James Stevenson, an African-American man, who owned five buildings in the neighborhood. This has all changed and Canada’s family is not the only one that has suffered. San Francisco’s African American population has dwindled to less than 6% from over 13% in 1970.

By April of last year, a judge ordered that Canada could stay in her home if she paid her opponent’s legal fees; $160,000. Canada was given two options if she wanted to stay in the home filled with the furniture her late husband made: pay the legal fees or sign documents that would pave the way for a condo conversion. She did not have the means to pay the legal fees and so continued to delay the eviction until her locks were finally changed by Sheriff Vicki Hennessy last month.

The Owens’ say the legal battle has hurt them too. Owen’s had to resign from his job as housing director in Burlington, Vermont after Canada’s story caused a backlash. He swears he willingly gave Canada the life estate: “Do you also remember the first time we met in your living room in the summer of 2002? You were in tears at the prospect being evicted. I re-assured you we’d figure out how you could stay in your home. I made good on that promise (though some suggested I was foolish to do so). All I am asking is for you to show me the same respect in return,” Peter wrote to Canada, demanding she sign the application for condominium conversion.

Sometime before Canada passed away she looked into a camera and left a message for Owens: “Peter, I can’t believe you did me like this,” she said.

People on both sides of the case have hurled accusations of greed and exploitation of the elderly. It’s true that Canada wouldn’t have been able to buy her home, that she may not have had the means to stay in her residence long term, that perhaps in her ill health many other people spoke on her behalf as they portrayed to have her best interests at heart. But no matter who is accused of greed — the landlord who fought an ugly legal battle for over two years or the niece who spoke on behalf of her aunt and juggled allegations of exploiting her condition — the fact remains a 100-year old woman died last week mourning the loss of her home in a city she called home for half a century.

For many, Canada’s struggle to keep her home narrated a story of a city that appears to be betraying its life-long residents, it became a rallying cry for the soul of the city and a battleground for people of color to keep their homes and remain in this city. Canada’s death is a cruel reminder that evictions can be a death sentence and there’s no mercy not even if you’re a 100 years old.

With additional reporting from Tony Robles