I was around in 1986, when the San Francisco Chronicle, along with most of the political power structure of the city, argued that Proposition M, a measure to limit office growth, would be the death of San Francisco.

Development limits, we were told, would destroy the booming economy. Reducing office space would bankrupt the city, put thousands out of work, send jobs to other places, and leave us with mass unemployment and no money for essential services.

Funny how that didn’t happen.

Prop. M probably saved San Francisco from the fate of other cities that allowed the office boom of the mid-1980s to grow out of control; when the bust hit, Houston (with no growth limits) looked more like the disaster that the Chron and then-Mayor Dianne Feinstein predicted for San Francisco.

That’s because the “growth-is-always-good” crowd ignored economic reality. The office boom of the 1980s was driven by an excess of speculative investment capital, created by the Reagan-era deregulation of Savings and Loan Institutions and new tax laws that allowed developers to make money on an office building even it hardly anyone occupied it.

And the bust cost the taxpayers hundreds of billions of dollars.

The Prop. M office limits – which restrict new construction to 875,000 square feet a year – clearly haven’t destroyed the local economy or the city budget, which is now at least five times the size it was in 1986.

The city is not mired in vast unemployment.

The problem, of course, is the opposite: The tech boom has created so many jobs, and so little affordable housing, that tens of thousands of San Franciscans have been forced out of town. Prop. M has not prevented San Francisco from becoming perhaps the richest city in the history of civilization – and the one today with the worst economic inequality in the nation.

And now, when activists are trying to control displacement by limiting office growth when there’s not enough affordable housing for the workers, the Chron and the city’s economist are issuing the same grave warnings that were demonstrably wrong in 1986 and are demonstrably wrong now.

Here’s the Chron headline: “Prop. E office limits would slash jobs, hurt incomes.” And the story:

San Francisco’s economic growth would be stunted, with the city losing tens of thousands of jobs and billions of dollars of gross domestic product, if voters pass Proposition E, which would tie office-space approvals to affordable housing goals, according to a report from the city’s chief economist, Ted Egan, released Monday.

I read the report. It’s based on some fundamentally faulty assumptions — and even then doesn’t say anything as apocalyptic as the Chron suggests.

But never mind: The No on E campaign is using the report, and the Chron story, to try to convince voters that Prop. E would destroy the city.

The language of the No on E ads, which are appearing on Facebook, mirror what the Chamber of Commerce says in its argument against Prop. E:

Prop. E would cut $600 to $900 million in affordable housing fees paid by office space over the next 20 years.

Yes, it would. Absolutely.

But it would also cut demand for affordable housing by far, far more than that. As we noted back in December:

The buildings the Chamber wants to see constructed would create a demand for $1.8 to $2.7 billion worth of affordable housing; the fees would cover about a third of that. Not building those towers would do more for the housing crisis than building them (at the current fee rate).

That’s the key here: Office developers pay fees for affordable housing. But those fees are far, far lower than the demand those buildings create. So more office space — at the current fee structure — makes the affordable housing crisis worse.

And the evidence is also really, really clear that new office buildings create more demand for Muni, police officers, and other city services than they pay for. By far.

So limiting office growth is actually good for the city budget. It’s also, in the current world, good for preventing evictions and displacement.

And the idea that this will lead to massive unemployment has no basis in fact. According to the report

This level of office development could support approximately 2,375 fewer office jobs per year.

Seriously? We could lose 2,375 jobs a year? There are currently more than 750,000 jobs in San Francisco. We gain and lose that many jobs every couple of months, just with the normal ebb and flow of capitalism. The impact on the city’s employment would be … three tenths of one percent.

That’s far too small to predict with any sort of accuracy.

But that’s not even the worst of this report.

From the document:

The proposed measure raises the issue of the relationship between employment growth and housing affordability in the city.

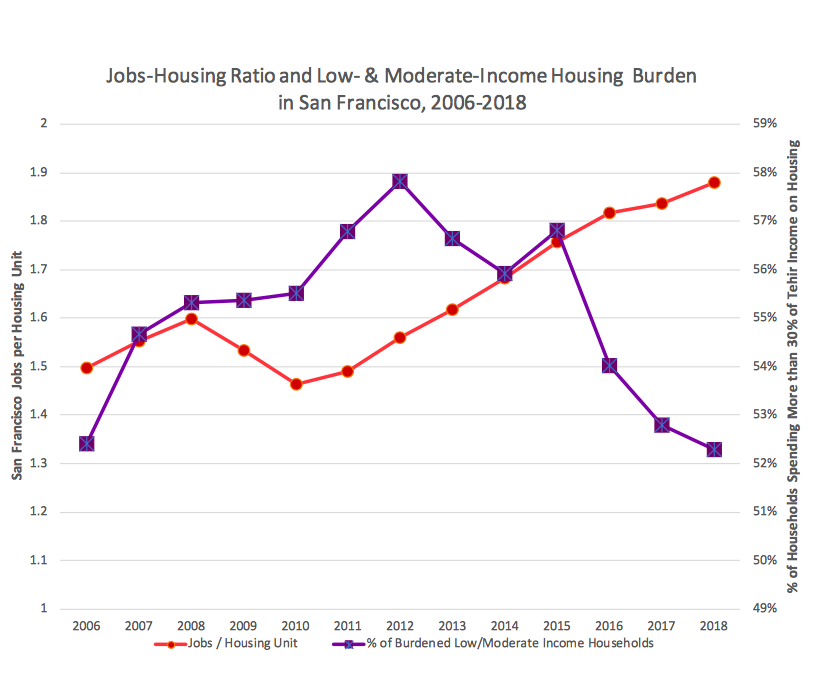

Employment growth clearly grew faster than housing supply in San Francisco during the 2010s. The chart to the left shows that the city’s jobs/housing ratio has risen by more than 25% since 2010.

However, while the housing burden facing low- and moderate-income San Franciscans remains very high, housing appears to have become more, rather than less, affordable as the jobs-housing ratio has increased during the 2010s.

According to Census data, the percentage of low/ moderate income households in the city spending more than 30% of their income on housing has tended to decline since the end of the recession.

There’s a nice chart that goes with this statement, which suggests that the rising tide has lifted all boats, that the tech boom has been just grand for lower-paid people, and that all has been well in the San Francisco housing market since the end of the recession.

But there are two key missing points here.

First, the only reason that existing low-income households have seen their cost of housing rise slower than their income is rent control. The folks who are still here are the ones living in rent-controlled apartments or in private homes that they bought many years ago.

Second, and far more obvious: tens of thousands of low-income households have been forced out of town by the tech boom’s speculation and evictions.

As John Elberling, the author of Prop E, notes:

Rather than state the obvious fact that this is because of accelerated displacement of lower-income households from the city – which means they are disappearing from that data! – and so of course the numbers about those who can afford to stay here look better after that …

… instead the office regurgitates the same old trickle-down baloney:

“As shown on the next page, one reasons for this seems to be that job growth has fueled growth in household income, which has been faster than growth in housing costs, for most households in the city.”

What that hides is that this is because new tech workers with higher income are replacing former city residents with lower incomes who have been priced out of their homes! It’s call “statistical substitution.”

But it’s REAL PEOPLE who are being “substituted.” they are not just “data points.”

We know that the current system of growth is doing deep damage to the city. We know that developers are not paying anywhere near the cost of providing affordable housing for the workers of their buildings.

We know that all of these pro-growth folks said the same thing in 1986, and it was totally wrong.

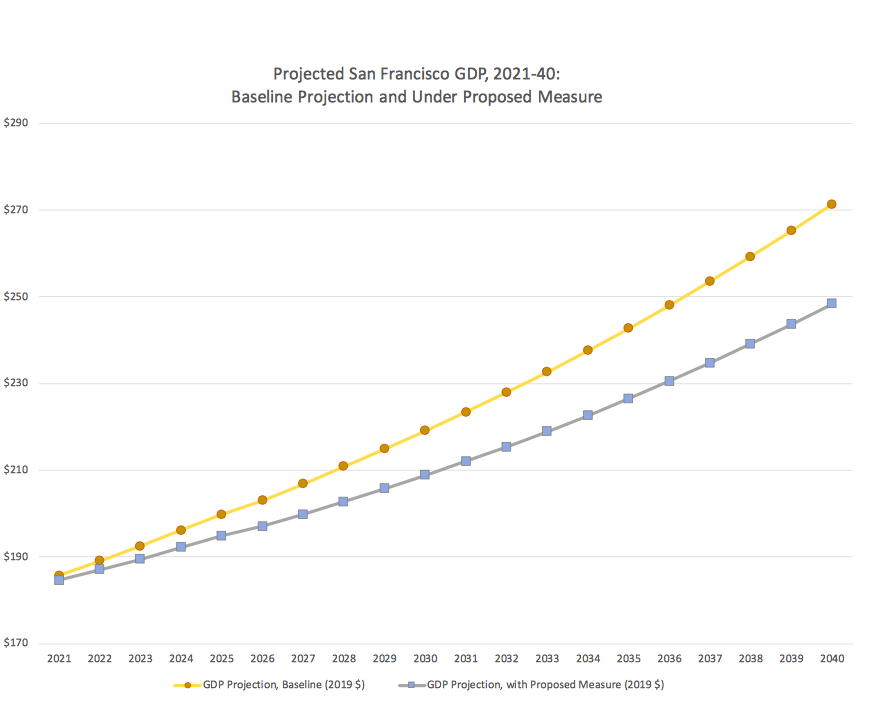

Oh, and by the way: This chart that shows how the city’s GDP would grow more slowly under Prop. E is misleading.

For starters: The chart shows that even with Prop. E, the local economy would grow 31 percent by 2040. Of course, with the national and global economies changing so fast right now, there’s absolutely no way to know what will happen to one city between now and 2040. Anyone who made a prediction 20 years ago about the city’s future would have been stunned by what has come to pass.

I don’t know if the SF GDP can actually grow by 31 percent in 20 years – or if we want it to. The global climate crisis may well be an argument for slower growth in the developed world, possibly even a steady-state economy (which would use less energy and goods).

In fact, I could argue that in the next 20 years, either we will slow our use of energy and material or climate change will cause such an economic crisis that the world will be in a deep recession.

But let’s say we want growth like this. Since Prop. E exempts all the office space already approved, which is about five years’ worth under the current Prop. M limits, there should be no change from this measure in the lines on the chart until 2025. So any divergence would be smaller.

“It’s typical ‘growth-is-always-good’ propaganda,” Elberling notes. “Of course it omits/ignores the human costs of growth. The lives of our city’s people is the most important criteria of all.”