An unlawful search warrant and gag order that San Francisco police and a magistrate judge imposed recently on the San Francisco Bay Area Independent Media Center was one of a long line of abuses of journalists by local government entities, and it underscores again that press freedom and source confidentiality protection laws don’t by themselves do the job. Some other cases in point:

● Nick Varanelli, a Sacramento City College photojournalist, was arrested while covering a San Francisco antiwar rally in March 2003. He had shown police his press ID, but officers at the scene said students didn’t qualify as actual journalists and he had to move on. He continued photographing, was arrested, and spent eight hours in jail before his father came to spring him. The district attorney later dropped bogus charges of rioting and blocking traffic.

● San Francisco sheriff’s deputies assaulted four credential-bearing journalists who were covering a political protest in City Hall in May 2016. Injuries to two of the journalists were so serious as to necessitate hospitalization.

● San Francisco police, acting on five unlawful search warrants, raided the home and office of freelance journalist Bryan Carmody in May 2019, handcuffing him for six hours and seizing professional equipment that police hoped would reveal who had fed Carmody details on the death of Public Defender Jeff Adachi. Police Chief William Scott offered the bogus excuse that Carmody was suspected of obtaining the information as part of a theft ring. In fact, Carmody had received it—legitimately—from a Police Department insider. At least two of the five judges involved knew that Carmody is a journalist but issued the warrants anyway, in clear, flagrant violation of California’s journalists’ shield law.

And from what appears on the application for the search warrant against the S.F. Bay Area IMC, better known as the grassroots news website Indybay, it’s plain that both police Sgt. Michael Canning, who signed the application, and San Francisco Magistrate Judge Linda Colfax, who issued the warrant, knew or should have known that Indybay is a news outlet, and that (1) both documents thus violated California’s Shield Law protecting the right of journalists and news media to keep information source identities and unpublished/unaired materials private, and (2) Judge Colfax’s order that Indybay keep silent about the search warrant and the reason for its issuance violated the First Amendment protection against prior censorship.

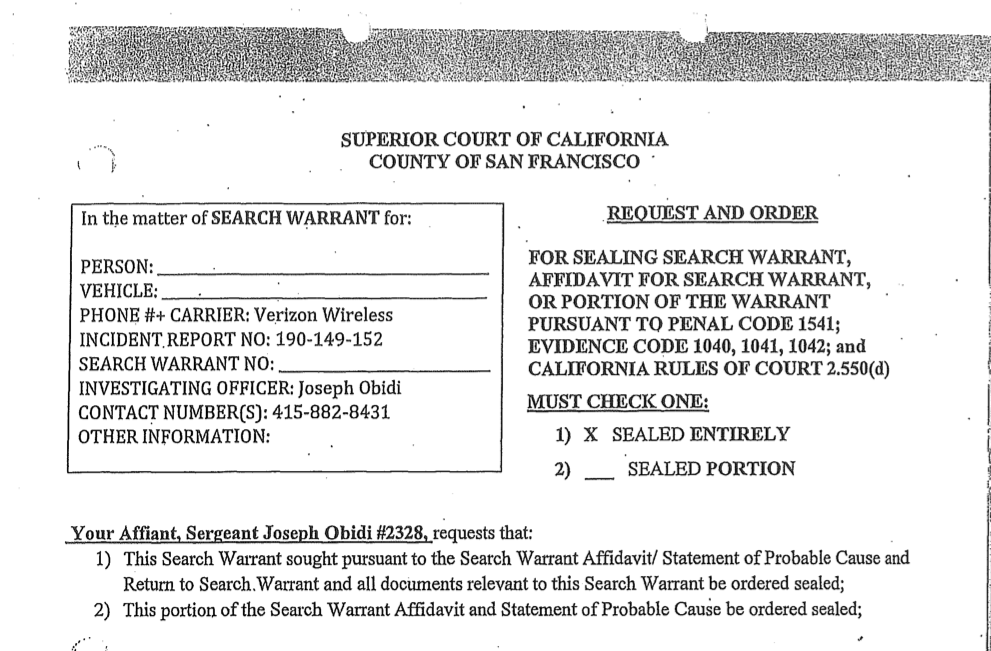

(The Electronic Frontier Foundation, which helped Indybay pro bono to beat back the warrant and the gag order, provided a copy of the warrant and the application to 48 Hills. Readers can access it here.)

What was the Canning- and Colfax-damning evidence that appears on the application? Indybay’s own, “About Us,” description of its activities:

The San Francisco Bay Area Independent Media Center (Indybay) is a non-commercial, democratic collective of bay area independent media makers and media outlets, and serves as the local organizing unit of the global Indymedia network.

Principles of Unity: San Francisco Bay Area Indymedia

- We strive to provide an information infrastructure for people and opinions who do not have access to the airwaves, tools and resources of corporate media. This includes audio, video, photography, internet distribution and any other communication medium.

- We support local, regional and global struggles against exploitation and oppression.

- We function as a non-commercial, non-corporate, anti-capitalist collective.

Canning quoted also from Indybay’s stated “Editorial Policy”:

The Indybay newswire operates on the principle of open publishing, an element essential to the global Indymedia network. Simply put, open publishing is to news and information what open source code is to software. In practice, the open publishing newswire allows anyone to instantaneously self-publish their work on https://www.indybay.org.

People are encouraged to “become the media,” to use their own skills and abilities of observation, writing, and creativity in posting text, video, audio, photos, and artwork directly to the website. The post is then viewable at the top of the breaking newswire.

What triggered the application and warrant was publication on Indybay’s newswire on Jan. 18 of what Indybay called “a pseudonymous communiqué by ‘some anarchists’ … claiming credit for smashing 18 windows at the San Francisco Police Credit Union that night. It stated that the building was ‘attacked for Tortuguita.’ Tortuguita, active in the struggle to stop ‘Cop City’ in Atlanta, was shot and killed by Georgia state troopers on January 18, 2023.”

Police wanted the digital Internet Protocol address “and other identifying information about the author of the communiqué,” Indybay recounted. Indybay’s full account is available here.

It’s one thing to subpoena for a specific piece of information and another to issue a search warrant, First Amendment attorney Thomas R. Burke, who represents 48 Hills and represented Carmody and quashed all the warrants issued against him, told me. A subpoena is “like a sniper shot” while a search warrant is “like a dragnet (that) steals the entire newsroom. Seizing a laptop (computer) or a cell phone – these days is the seizure of an entire newsroom because hundreds of investigations and their sources and other unpublished information are likely to be captured. That (search warrant) is never going to be permissible,” said Burke, who taught media law at UC Berkeley’s Graduate School of Journalism for nearly two decades and is a partner in the law firm of Davis Wright Tremaine.

Even a subpoena, though, is unlawful if it is an attempt to pry loose a journalist’s confidential-source ID or unpublished/unaired materials.

California’s Shield Law is codified in state Constitution Article I, Section 2, and in state Evidence Code Section 1070. Both declare that journalists shall not be held in contempt by a government entity for refusing to identify an information source or to disclose unpublished information.

Perhaps equally powerful is state Penal Code Section 1524(g): “No warrant shall issue for any item or items described in Section 1070.”

Many press-freedom activists believe current laws suffice to protect journalists from abuses such as those described above and to provide remedies when those abuses occur. Respectfully, I disagree. And I am not the first to do so publicly. For instance, Tim Redmond, 48 Hills’ founder and editor, has long argued for rules and regulations that would hold Shield Law violators’ feet to the fire.

The journalism community shares responsibility for protecting its own. Burke recalled that a number of reporters covering Carmody’s post-search-and-seizure court fight questioned aloud on whether he was a journalist. “I had to remind them that he carried an SF Police Department media credential,” Burke said.

When freelance video-journalist Josh Wolf spent 226 days in federal detention, in 2006-07, for refusing to surrender footage of a July 2005 protest demonstration in San Francisco, Chronicle political columnist Debra Saunders said he didn’t qualify as a journalist because he worked without an editor looking over his shoulder, but that he should be released anyway because keeping him locked up cost too much taxpayer money—all this notwithstanding that the Society of Professional Journalists contributed $30,000 to Wolf’s legal fight.

Back to the main question: Mario Trujillo, who led the EFF legal team representing Indybay, told me that “the most important piece of this for me is making it as easy as possible to challenge these unlawful warrants in court. I think this overlaps with the accountability question you are asking. A few things that could help:

“● Creating local court rules that clearly outline the steps for challenging these warrants.

“● Making it easy to recover attorney fees if a news organization prevails.

“● If a warrant looks like it targets the press, allowing for an adversarial hearing before the warrant is issued.

“● Making it easier to recover damages from police in subsequent civil rights lawsuits when constitutional rights are at issue.”

Burke pointed to the state Commission on Judicial Performance as a possible avenue for holding judges accountable when they violate journalists’ rights. The commission is, according to its website, “the independent state agency responsible for investigating complaints of judicial misconduct and judicial incapacity and for disciplining judges, pursuant to article VI, section 18 of the California Constitution.”

Judges and police personnel showing a pattern of violating journalists’ rights should face penalties up to and including dismissal, Burke said.

Amen.

Richard Knee is a San Francisco-based freelance journalist and sunshine and First Amendment activist.