The stirring strains of “Nicaragua, Nicaraguita” played over the loudspeakers as thousands poured into the Plaza of the Revolution on July 19, 1983. Young people with raised fists and red-and-black bandannas, peasants in crisp white guayaberas and wide-brimmed straw hats, women in military uniforms rifles on their shoulders. They cheered when President Daniel Ortega spoke about the literacy campaign, the free health clinics, the new agricultural cooperatives on land seized from Somoza’s cohort of oligarchs.

It was a heady moment for the North American activists who had traveled to Managua to celebrate the fourth anniversary of the Sandinista Revolution. I was with a group that had attended a conference sponsored by the Sandinista Association of Cultural Workers, led by Ortega’s wife Rosario Murillo. Writers, musicians, painters, and filmmakers from all over the world had gathered to hear about the gains of the revolution from their Nicaraguan counterparts and pledged to use their skills to combat the lies and misinformation being spread by the Reagan Administration.

We gathered in the sweltering plaza with other internationalists — teachers, nurses, carpenters, engineers, agronomists, and volunteers who had come to help harvest the coffee crop, offering their best efforts to replace the skilled hands of agricultural workers who were defending their country against the US-backed contras.

I remembered that exhilarating day a few weeks ago when my friend Linda John asked me to sign a letter strongly condemning the increasing political repression under the current regime of Ortega and Murillo. The letter stated:

We the undersigned went to Nicaragua to support the heroic and noble efforts of the Nicaraguan people to rebuild their country into one of justice, equality and democracy. We also went to witness and oppose the illegal and immoral actions of our own government that violated the Nicaraguan people’s right to self-determination.

We are well aware of – and detest – the long, shameful history of U.S. government intervention in Nicaragua and many other countries in Latin America. However, the crimes of the US government – past and present – are not the cause of, nor do they justify or excuse, the crimes against humanity committed by the current regime of Daniel Ortega and Rosario Murillo … the targeting of women’s organizations, independent journalists, and environmentalists and indigenous communities opposing construction of the proposed canal.

We are outraged by the latest maneuvers to shut down all dissent,” the letter continues, “and by the arrests and detention” of civil society activists, all opposition candidates in the scheduled November elections, and the historic revolutionaries Dora María Téllez, Hugo Torres and Victor Hugo Tinoco.

Charging that the Ortega-Murillo regime “betrays the memory of tens of thousands of Nicaraguans who died for a democratic Nicaragua” the signers call for the release of political prisoners, repeal of the draconian national security law, and free and fair elections.

The full text of the letter, in English, is here.

I had been dismayed about the situation in Nicaragua ever since the deadly crackdown on demonstrations and the arrests of student and union leaders in 2018. But it was the arrest last month of the revolutionary leaders, especially Dora Maria Tellez, that drove to me to angry despair.

Tellez, a comandante at age 22, led the takeover of the dictator Anastasio Somoza’s national assembly, negotiating the freeing of key Sandinista political prisoners, and headed the liberation of Leon, Nicaragua’s second largest city and the first city to fall to the Sandinistas. After the victory of the revolution in 1979, she became Minister of Health, campaigning for LGBTQ and reproductive rights. Like many women activists, I had first heard of her heroism in Margaret Randall’s book “Sandino’s Daughters.”

With a heavy heart, I signed.

Yet that feeling of exhilaration returned when I learned that within a week, more than 500 supporters of the Nicaraguan revolution had also signed. Many were my partners in Friends of Nicaraguan Culture, others were from the Committee for Health Rights in Central America, Tecnica, the literacy campaign, and construction brigades.

I imagined that all signed with a heavy heart. I wanted to talk with them.

One of the originators of the letter, Garrett Brown, worked at the language school in Esteli, a town near the Honduran border, from 1984 through 1988. Brown lived with a family who, like many in that war-torn area, had lost sons and daughters in attacks by the US-backed contras.

“Living in revolutionary Nicaragua was a life-changing experience,” Brown said, “and we were all deeply touched by living with people who had sacrificed so much for the goals of the revolution – for education for their children, freedom from hunger, an end to the Somoza dictatorship.

“The abuse of power of the Ortega regime has nothing in common with what happened in revolutionary period and what millions of Nicaraguans fought for,” Brown added.

After we returned home from that ASTC conference, we formed Friends of Nicaraguan Culture and worked to stop the Reagan Administration’s attempts to crush the new Nicaragua.

We joined grassroots campaigns demanding an end to contra aid. We collected school and art supplies for Nicaraguan students. We organized delegations of US cultural workers to Nicaragua to see the gains of the revolution for themselves. We wrote articles, letters to the editor, pamphlets, and hundreds of flyers.

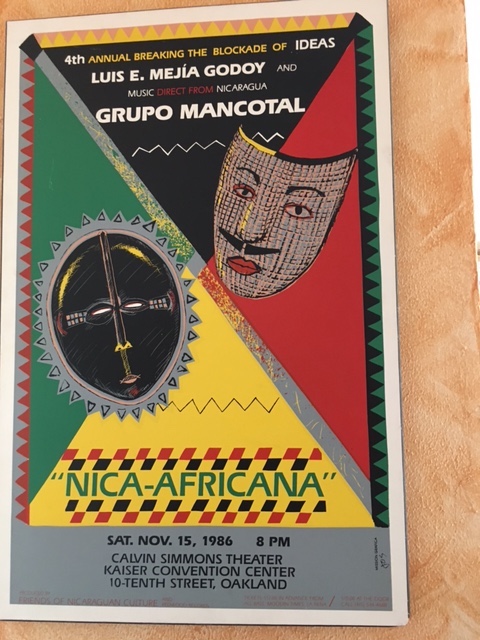

Under the banner, “Break the Blockade of Ideas,” we organized programs with Minister of Culture Ernesto Cardenal, musicians Luis Enrique Meíia Godoy and Grupo Mancotal, as well as dynamic political leaders Nora Astorga, a former guerrilla fighter who became Nicaragua’s ambassador to the United Nations, and Ray Hooker, a member of the National Assembly from the Atlantic Coast. Their music and inspiring words packed halls from La Peña and Glide Memorial Church to the Palace of Fine Arts.

Memories of these efforts came flooding back: press releases, venue rentals, posters, late-night meetings, fighting with the government over visas for our visitors. Thinking of the friends I worked side-by-side with, I contacted them about the letter.

Bobbie Camacho was a legal worker at the Oakland-based Asian Law Caucus. As a leader of FNC, she was particularly active in forging ties between the Nicaraguan solidarity movement and the Rainbow Coalition, labor unions, and women’s organizations. “As a Pacific Islander woman, I was inspired and motivated by the courage, dedication and perseverance of the Nicaraguan people’s pursuit for self-respect, dignity and their right for national sovereignty,” Camacho explained.

Camacho recalled that on one FNC delegation she met Foreign Minister Miguel D’Escoto during his international fast for peace. “We extended our hands of friendship, with hopes of peace and ongoing bonds of solidarity. That historic moment was inspiring and also very humbling — one that I will always cherish.”

FNC member Miranda Bergman was teaching art in elementary schools when she was invited to Nicaragua to paint a mural on the first children’s library in Nicaragua, Biblioteca Luis Alfonso Velasquez, in 1983. She called the mural “Los Niños Son El Jardin.”

“It was a great honor for me,” says Bergman, who returned in 1986 and painted “El Amanecer” on the Teachers Union building in Parque de las Madres in Managua.

Sadly, the library mural was covered with gray paint during the presidency of right-winger Arnoldo Aleman, who was later sentenced to 20 years in prison for corruption.

Linda John signed up for a Nicaragua Information Center trip because she had a deep curiosity about the revolution. “I had been active in the civil rights and anti-Vietnam War movements,” John said, “and I hoped for profound change for my country.

“I fell in love with the energy, the feeling of empowerment – although the people we stayed with were very poor, they were proud and unafraid. The police and local militia were the sons and daughters of people in the neighborhood. Ordinary people felt they had a voice and they dreamed big.”

John, a skilled barber, returned to Managua with a suitcase full of combs, scissors, perm papers, and other salon supplies and began to teach haircutting classes through the Nicaraguan women’s organization, AMLAE. She and her students set up shop in a garage and provided haircuts for women workers as well as wounded revolutionaries who came in wheelchairs.

Back in the US, John took part in many solidarity actions, including being arrested in a civil disobedience action in front of the Federal Building aimed at ending US support for the contras.

John is still in touch with some of the women she befriended in Nicaragua, many of whom feel afraid to even go out on the street because of the crackdown. “I signed the letter because I want to let people in Nicaragua that they are not alone, not forgotten.”

Documentary filmmaker Helen Cohen was teaching English in Cuernavaca when she volunteered on a coffee-picking brigade in 1983. She later worked for two years on the Atlantic Coast in construction and supporting local cooperatives. “There was a palpable feeling of joy, liberation, solidarity and cooperation that permeated the country,” Cohen said.

Cohen signed the letter because she now feels “overall sadness, distress and outrage at the repression and violence that has been unfolding in Nicaragua and the complete, heartbreaking 180 of the Ortega Administration.”

Mary Ellsberg, now a professor of Global Health and International Studies at George Washington University, first went to Nicaragua in December, 1979, only six months into the Revolution. She taught literacy on the Atlantic Coast and then worked for eight years in the Ministry of Health based in Bluefields, training popular health workers, called brigadistas, to respond to the most common health problems in their communities.

“During the US-funded Contra war, many of our brigadistas were killed or kidnapped, so I saw firsthand the terrible cost of US intervention against Nicaragua,” she said.

Ellsberg signed not only this letter but a similar one from more than 700 academics as well as a global letter of feminist solidarity.

“My son, Julio Martinez Ellsberg, is active in the opposition movement, and my father, Daniel Ellsberg, also signed the letter, so there are three generations of us involved in this solidarity effort with the Nicaraguan people.”

Ellsberg said she’s concerned that “many people on the left in the US still have a romantic view of the Sandinista Revolution of the 1980s, and believe that any opposition must be the result of US or CIA interference.” But like John, she said that “based on the hundreds of people I know in Nicaragua who are opposed to the Ortega regime, including many feminist activists, this is not true.”

Margaret Randall’s writings inspired many of us to learn about the Nicaraguan Revolution. “My love for Nicaragua motivated me to sign,” Randall explained. “it seemed the least I could do.”

Randall was friends with Ernesto Cardenal when they were both young poets in Mexico in the 1960s. “I knew many of the early Sandinistas when I still lived in Cuba during the final years of the insurrection,” she says. “Some frequented my apartment, where they used an old ditto machine that we had to print their circulars. And I lived in Nicaragua from the end of 1979 to the beginning of 1984, so I also experienced the Sandinista revolution on the ground. I shared the hopes involved in trying to create a society based on justice.”

Randall said, “I know that letters such as this one have a limited potential for creating change. What I hope is that it may help to put some pressure on the international organizations and institutions that can alter their diplomatic, economic and cultural policies towards Nicaragua.”

In that sense, the letter has already had an impact. Brown noted the US organizers are in touch with groups in Europe who are gathering signatures for their own letter and has become part of a cumulative global effort, including condemnation and sanctions from the European Parliament.

On one of our FNC delegations, we met with Interior Minister Tomas Borge, a founding member of the FSLN, who greeted us warmly and told us “Solidarity is the tenderness among people.”

None of us imagined that almost four decades later our solidarity would be expressed as a signature on a letter to the first Sandinista president calling for an end to political repression.

And yet we signed.