Duboce Triangle artist isn’t at fault here, no matter what C.W. Nevus says — and tenants actually have a right to stay in their homes

By Tim Redmond

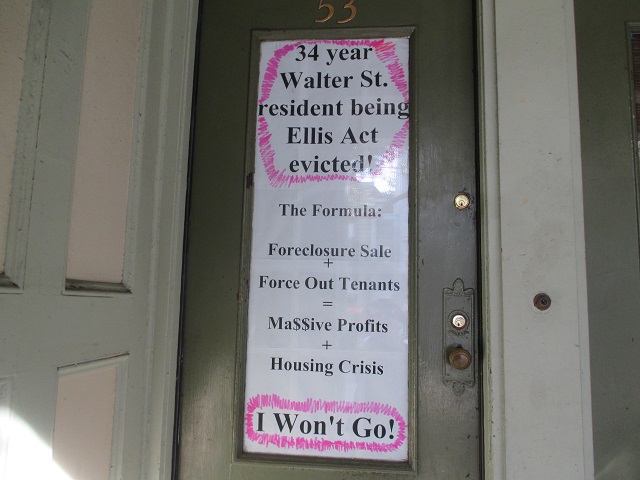

OCTOBER 26, 2015 — David Brenkus is not a bully. He’s a soft-spoken cabinet-maker and experimental photographer who arrived in San Francisco the same year I did, 1981, and has lived for 34 years – quietly, with no problems – in an apartment near Duboce Park.

But the SF Chronicle’s C.W. Nevius has turned him into some sort of a monster who is terrorizing his (wealthy) (tech industry) landlords, who say they are just trying to evict him to make room for a family home.

In the process, Nevius allowed notorious eviction lawyer Andrew Zachs to make a completely inaccurate statement without the dispute – one that ignores the intent of more than three decades of tenant law in this city.

Here’s Zachs:

“It’s this self-entitled expectation that you have this God-given right to live here forever because you came here 30 years ago,” said Andrew Zachs, the Harshawats’ attorney. “That’s not how it works. Renters pay, they stay in a place and when the lease is up, they give it back.”

Untrue, Mr. Zachs.

In San Francisco, when you rent an apartment, you can stay for as long as you continue to pay the rent and abide by the terms of the lease. A tenant does, in fact, have a right to live in a place forever (not given by God but by the San Francisco Board of Supervisors and mayor), and can only be evicted for “just cause.”

The fact that your rent is way below “market-rate” is not a just cause. The fact that your landlord could make a lot more money by getting rid of you is not “just cause.”

Oh, and when you buy a residential building in San Francisco that has tenants in it, you get the tenants – with all of their rights – as part of the deal. Don’t want to be a landlord? Don’t buy a building with tenants in it.

So here’s the story that Nevius missed:

In 1981, after leaving Brown University and the London School of Economics, Brenkus arrived in SF and moved into a place on Walter Street. He lived with roommates on the third floor; that’s how most of us lived in those days. You got a room in a flat through a roommate referral service, and met new people and figured out a life in the big city.

The first floor unit was occupied by a group of Laotian refugees – between 12 and 25 at various times, Brenkus told me. The rest of the building, including his apartment, “was the United Nations for 20 years,” with people from more than a dozen countries arriving and moving in.

Brenkus gave up academia and instead wound up working as a cabinet-maker and union carpenter. Every piece of furniture, every fixture, the back deck, the bathroom, the kitchen, and most of the walls is in mint condition thanks to the work he did (free) on the place. “One of the reasons the landlord kept my rent low is that I was doing so much to add value to his place,” Brenkus told me.

A friend and sometimes business partner operated an art gallery in Paris, and there, while learning to make frames for classic paintings, he got introduced to the art world.

And after a while, it took over his life. He began taking pictures with an old camera and a wineglass instead of a lens. He bought used equipment and built (with the landlord’s permission) a darkroom in his flat. After badly hurting his back (fixing up the basement of the place) he let carpentry go, and his art became his life.

I am not an art critic, and Nevius and Zachs seem to think that a person is not an artist unless he is on the Internet. But I went and visited Brenkus in his place, and I have to say the work he does is stunning.

More important, he’s what San Francisco used to be about. When I got to town, most of the people I knew worked part time at jobs that just payed the rent while they focused on theater, music, poetry, visual art, or politics. There was nothing wrong with the idea that cheap rent subsidized some form of creativity that wasn’t in the mainstream. It’s where the best and most beautiful ideas in the city came from.

The landlord at 53 Walter Street was a family patriarch named Acosta who slowly built up something of a small-scale real-estate empire; at one point he owned 14 buildings in the city. His kids eventually occupied the two units below Brenkus. Everyone got along fine.

Then shortly before he died, Breknus told me, Acosta bet the farm on a development venture in Bayview; he leveraged all of his property in 2008, just before the real-estate bust hit, and wound up losing everything.

His kids fought through a bankruptcy, and in 2013, the bank forced them to sell the Walter St. building. The Harshawat family – Ish, Kavi, Paras, and Roompam – bought it for about $1.3 million, city records show.

That, to say the least, was a huge bargain. The place needs work, but part of the reason it sold so cheap was that it was occupied by long-term tenants.

In San Francisco, when you buy a building, you don’t just get to throw all the occupants out. You are informed by the seller what the existing rents are, and if those numbers don’t pencil out, you can pass on the deal.

In this case, the Acosta family members left, but Breknus stayed.

Nevius portrays the landlords as innocent folks who just want to move their family into a building they own. In a press statement, the family says:

We are not evicting Mr. Brenkus to make a profit on this property, we are simply trying to move our growing family into our home and start a life here. We are well within our legal rights to do so.

The Harshawats purchased the three-story building in Duboce Triangle in 2013 and planned to move their family into the units – the grandparents on the bottom floor and the two brothers and their families on the top two floors.

According to the Anti-Eviction Mapping Project, which does some of the best research in the city, the grandparents – Dr. Paras Harshawat and his wife Roopam – run a private psychiatric hospital in Indiana. They have not sold their home in the Midwest, and if they are planning to move to a much smaller place in SF, they haven’t shown any signs of it.

The brother, Kavi Harshawat, took a job with the Department of Veterans Affairs in Washington, DC eight months ago, according to his LinkedIn profile. Unless he’s about to quit that job, he isn’t about to move into a place in San Francisco.

I left a message for Ish Harshawat, who Brenkus said was the person handling the interaction with him and who is living with his wife, Emma Acker, a curator at the De Young Museum and their newborn daughter in the unit under Brenkus’s. I have not heard back.

But as far as I can tell, this isn’t exactly the case that Nevius described of a poor family just trying to use its own property.

In fact, if the family really was going to move in, Andrew Zachs knows that an Owner Move-In eviction is cheaper, faster, and easier than an Ellis Act case. But in that case, the owners actually have to move in, and make the place their primary residence. And if it turns out they don’t do that, the former tenants can sue for wrongful eviction.

In this case, the Harshawats have chosen to evict Brenkus under the Ellis Act, which is more difficult but doesn’t require anyone to live in his unit.

The Harshawats offered Brenkus money to leave. Nevius says it was $130,000; Brenkus told me it was $80,000. (Also, the rent Nevius reports is wrong; Brenkus pays $365 a month because he splits the $735 a month rent with a roommate.) And the $80,000 offer, he told me, included $26,000 in compensation for the work he did on the place (and if you’ve seen it, as I have, that’s a hugely insulting offer.)

The bottom line is that even at $130,000, after taxes and moving expenses, Brenkus could in no way stay in this city in a place where he can do his work for more than a year or two.

What he wants isn’t money: It’s the right to stay in his home. Which isn’t really that radical a concept.

Again: If you buy a building with a tenant in it, you need to understand that in San Francisco, you can’t just assume that tenant is going to leave.

San Francisco used to be a city where people were into art not for high-end commercial reasons but because that’s just what they do. Brenkus is a symbol of that, a part of the city’s past that the tech boom is destroying.

And if the Harshawat family members don’t understand why tenant activists are so angry, and why they are facing loud doing protest actions, they haven’t been paying attention to this city.