And this week provides a particularly impressive array of events from classic Hollywood to vintage world and experimental cinema, taking place at various SF and Berkeley venues without even the excuse of a film-festival umbrella. We can congratulate ourselves: For the time being, at least, we remain a community that can support this range of retro celluloid activity (even if most of it is probably being projected digitally).

Though by no means exhaustive, the following are our chosen cream of an exceptional week’s programming crop:

Come and See

Arguably the premier revival event of last year was the restoration of the gargantuan eight-hour 1960s Russian epic War and Peace, whose popular marathon shows were reprised several times at both the Castro and Pacific Film Archive. Equally overwhelming in its way is this late-period Soviet classic from director Elem Klimov, who never directed again. He considered that with this final work he’d said everything he had to say, and when you see it you’ll understand why.

Somewhat autobiographically inspired, the 1985 feature centers on Flyora (Aleksei Kravchenko), a Belarusian boy of just 14 or so who’s thrilled to be conscripted by partisans in 1943—even as his already probably-widowed mother despairs at how she and his sisters will survive alone. But the boy’s naive expectations of heroic adventure are almost immediately dashed amidst the brutality and chaos of Nazi invaders.

There’s not much “plot,” per se, but Come and See is far from a mere catalog of war’s horrors. Instead, it’s a bravura waking nightmare with alternating elements of magical realism, harsh violence, humor, terror, docudrama, and lyricism. At times almost unbearably intense—more in psychological than graphic-content terms—it makes credible the reports that lead actor Kravchenko, who really was just 14 when filming started, suffered PTSD afterward. Considered one of the great anti-war movies, and/or just one of the greatest movies, period, this newly restored masterpiece is indeed an extraordinary experience. Roxie, Fri/6 & Sun/8 (but check the Roxie calendar for possible added screenings). More info here.

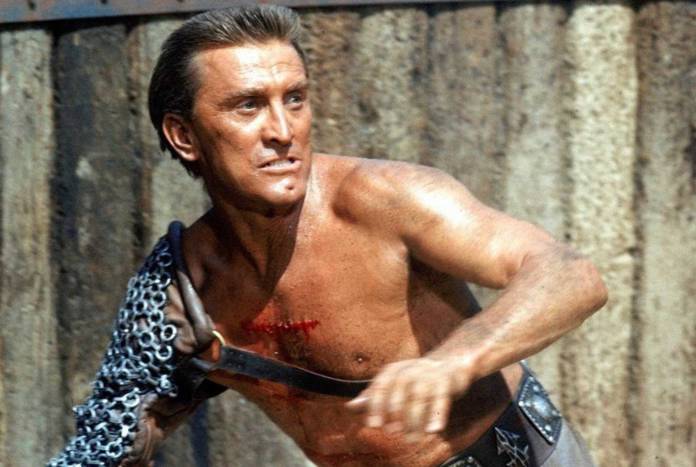

Kirk Douglas tribute at the Castro

When Douglas died a month ago at age 103(!), you could almost say the last of the great “golden age” Hollywood movie stars was gone. (Only “almost,” though, because same-aged Olivia de Havilland is still hanging in there.) Along with peer Burt Lancaster and some others, he was both product of that old-school studio star system and an agent of its demise, as he aggressively pursued career independence as a producer and free agent.

An assertive, “virile,” frequently intense (as well as occasionally hammy) performer who did not disappear easily into more passive characters, Douglas was nominated for an Oscar three times in the 1950s, finally grabbing an honorary statuette for his overall career decades later. His social conscience was conspicuous—he virtually ended the Hollywood Blacklist by insisting writer Dalton Trumbo be credited for Spartacus—and his artistic preferences led to some interesting enterprises as both actor and producer. The Castro is paying tribute with a number of representative double bills throughout March, beginning Sun/8, beginning with classic 1947 noir Out of the Past (in which he played a villainous supporting part) and from a decade later, western Gunfight at the O.K. Corral, one of his several teamings with Lancaster.

The series continues on Mondays with a stellar lineup: Vincente Minnelli’s Tinsel Town tell-all The Bad and the Beautiful with Billy Wilder’s bitter Ace in the Hole on the 15th; Kubrick’s anti-war classic Paths of Glory and the 1962 revisionist western Lonely Are the Brave on the 22nd; Van Gogh biopic Lust for Life and the inevitable Spartacus on the 29th. More info here.

Francis Ford Coppola and 50 Years of American Zoetrope

Disillusioned by his first experiences working within the creaking Hollywood studio system, young Coppola moved operations north to SF, founding his own production company with pal George Lucas. Their mission of making more personal, artistic films was fulfilled by Zoetrope’s first two features, Coppola’s own road-trip drama The Rain People and Lucas’ debut feature THX-1138. Both were commercial flops—which forced FFC into the for-hire gig of The Godfather, whose box-office bonanza considerably raised the new company’s fortunes.

Those three features kick off this series that celebrates Zoetrope’s 50th anniversary, followed on Sat/14 by 1963’s Dementia 13—one of many low-budget Psycho imitations around that time, but a superior thriller as well as the finest of Coppola’s early dabblings in exploitation cinema. Later on, the partial retrospective offers a mix of his personal projects (The Conversation, One From the Heart), other idiosyncratic expressions Zoetrope helped steer to the screen (Paul Schrader’s Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters, Godfrey Reggio’s Koyaanisqatsi), and works by foreign masters that it produced and/or distributed (Kurosawa’s Kagemusha, Godard’s Passion and Every Man For Himself). Though it’s gone through various permutations over the decades, American Zoetrope remains a Coppola joint: It’s currently owned by his children Roman and Sofia. Thurs/5-Sun/May 17, BAMPFA. More info here.

Fellini 100

The kind of auteurist filmmaking Coppola’s generation inclined towards wouldn’t have existed without the influence of a handful of postwar European mavericks, among which none was quite so bold or liberating as Federico Fellini. Like most Italians who joined the industry in the 1940s, he began in neorealism, working as a writer on significant early titles by Rossellini and Lattuada. That carried over into his first directorial efforts, but even then he was beginning to show signs of whimsy and fabulism which would soon explode into the phantasmagoria of La dolce vita, 8 1/2, and his later work.

This day-long Castro Theatre event from Cinema Italia San Francisco offers quadruple dose of Fellini to mark the centenary of his birth. (He died in 1993 at age 73.) Kicking things off is his 1954 international breakthrough, the pathos-drenched circus melodrama La Strada, in which the director’s wife Giulietta Masina plays a gamine in greasepaint who takes much abuse from Anthony Quinn’s big-top strongman. A decade later she’d star again as Juliet of the Spirits, in a sort of female equivalent to Vita and 8 1/2 that was Fellini’s first feature in color. For many, it heralded the beginning of a decline into directorial indulgence and self-imitation.

But the same critics were thrilled when another decade forward, he’d make all his by-then-familiar surreal and carnivalesque devices seem fresh again in Amarcord, a marvelous, somewhat autobiographical portrait of provincial childhood in the 1930s. After a “La Magia di Fellini” party featuring multiple pastas and an exhibition of Fellini’s own drawings, the program concludes with 1953’s I Vitelloni. A companion piece to Amarcord in a way, it similarly casts a wry, fond eye on the indolent lives of several small-town young men, albeit though a more straightforwardly neorealist lens. Sat/5, Castro Theatre. More info here.

(Note: The Pacific Film Archive is also hosting an ongoing, more extensive “Fellini at 100” retrospective through May 17, with a sidebar “In Focus: Federico Fellini” pairing guest lecturers with screenings.)

Jesus Christ Superstar

Though the movie musical was seriously flagging in the early 1970s following a string of expensive flops (all hoping to replicate The Sound of Music’s massive success), In the Heat of the Night director Norman Jewison scored a surprise smash with his 1971 version of Broadway’s long-running Fiddler on the Roof. Much of that zesty adaptation’s effectiveness was attributed to its being shot more-or-less “on location” (exteriors for the Ukrainian-village-set story were filmed in various parts of Yugoslavia), so it made sense for Jewison’s next project to follow suit.

Allowing him a neat thematic turn from Judaism to Christianity, Jesus Christ Superstar translated the Andrew Lloyd Webber/Tim Rice “rock opera” to the screen, with the novelty of being shot again kinda-sorta “where it happened”—on largely Israeli “Holy Land” sites where Jesus might well have trod. Sue me, but I still think this was a big mistake: While Fiddler was “naturalistic” as musicals go, JCS was always intended to be a wildly theatrical, hip, exaggerative take on an already-larger-than-life (or death) religious tale. Setting it amidst realistic, desert-y MIddle Eastern backdrops was a poor fit to the very “now” (c. 1970) flamboyance of the music, lyrics and general semi-camp ambiance.

Nonetheless, it’s the only big-screen Jesus Christ Superstar we’re likely to get, so it remains a favorite for many, despite its mixed-bag reputation. This screening (which marks the show’s 50th anniversary year) will feature live appearances by Ted Neeley, who also played the title role onstage both before and after the film, and “Mary Magdalene” Yvonne Elliman, who had a chart-topping disco hit in 1977 with the BeeGees’ “If I Can’t Have You.” (Carl Anderson, who played Judas, died of leukemia in 2004.) They’ll take questions onstage before the movie. Thurs/5, Castro Theatre. More info here.

16mm Punk Restorations at Other Cinema

Staying in a musical mode, Other Cinema’s program this Saturday offers a host of 16mm punk-scene shorts that Peter Conheim has restored for the collection “Eyes, Ears and Throats, 1976-1981.” It will include memorable early music “videos” by The Residents and Devo, Liz Keim’s In the Red about SF’s Fab Mab, plus audiovisual material on such local legends as The Offs, Dead Kennedys and Avengers. Don’t miss Richard Gaikowski’s 1980 Moody Teenager, in which a longhaired lass (Susan Pedrick) gives herself a series of increasingly radical makeovers to the sounds of James White, Lydia Lunch, Suicide and others. Sat/7, Artists Television Access. More info here.

Aliens and Victorians at the Alamo

Two semi-live events at Alamo Drafthouse this week further spice up its usual sidebar programs of revivals and genre favorites. On Tues/10, historian Mallory O’Meara will host a screening of 1953 sci-fi classic It Came From Outer Space. Anticipating Invasion of the Body Snatchers, among other things, it finds an American small-town populace beginning to “change” under the influence of what turns out to be stranded interplanetary visitors. (Who, when finally glimpsed, turn out to look halfway between “sea monster” and H.R. Pufnstuf.) Originally released in 3-D, it was the first sci-fi feature from director Jack Arnold, who’d direct other genre classics of the era (including Creature from the Black Lagoon and The Incredible Shrinking Man) before spending later decades toiling on TV series—his final credits were for The Love Boat. More info here.

The next night, a different strain of fantasticism will be on display with Jan Svankmajer’s 1988 Alice. It’s a striking, surreal interpretation of Lewis Carroll rendered in the master Czech animator’s distinctively creepy/beautiful stop-motion style. There will be a pre-film live drag performance from local ensemble Media Meltdown, which describes itself as “a queer celebration of weird pop culture and cults of nostalgia.” More info here.