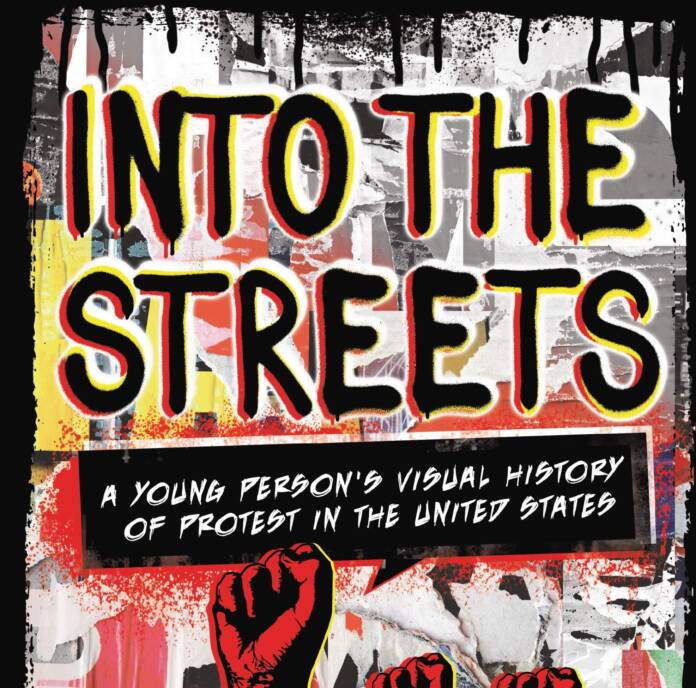

“Into the Streets: A Young Person’s Visual History of Protest in the United States” by 48 Hills publisher and arts editor Marke B is out today on Lerner Books (available everywhere, but please support your local bookshop and Bookshop.org). It’s already been called “a must-read for understanding our current times” (Book Riot) and “a thoroughly representative book” (Kirkus Reviews), and received positive reviews from School Library Journal and ALA Booklist.

The colorful, image-packed book—which is great for adults, too—details the history of protest in the territorial United States, from America Indian resistance and slave rebellions to Greta Thunberg’s climate strikes and #MarchforOurLives. Along the way, “Into the Streets” covers such pivotal moments in resistance history as the Great Railroad Strike, the Women’s Suffrage Parade, the Occupation of Alcatraz, the Attica Prison Uprising, and the Ferguson protests—alongside more familiar movements like the Civil Rights Movement, Stonewall, the Delano Grape Boycott, and the Vietnam War protests. Through it all, the leadership of youth, the cultural expressions, and the deep work that goes into protest movements are highlighted.

To tell you more about the book and its context, we’re reprinting this interview-conversation with Marke by writer Elizabeth Dulemba, which originally appeared on her website on June 11.

With the recent protests, Marke Bieschke‘s new book INTO THE STREETS: A Young Person’s Visual History of Protest in the United States suddenly became even more relevant. Lerner Books bumped up the publication date. So, I am proud, proud, proud, to have Marke here today to talk about this important book.

e: Marke, This is an incredibly timely book. What was the spark that inspired the making of Into the Streets?

Marke:

Hi, Elizabeth! Thanks so much for having me here, virtually. Into the Streets came about when Zest publisher Hallie Warshaw and I were brainstorming book topics that hadn’t been covered too much in the past, and which would naturally flow from my last book, Queer: The Ultimate LGBTQ Guide for Teens. That book pointed out how much LGBTQ rights depended on marginalized people bravely raising their voices in protest, sometimes rioting and putting themselves directly in physical danger—and also social danger, since being “exposed” as gay or lesbian in the 1960s and ‘70s, when the contemporary gay rights movement began, could mean loss of your career, your home, and your family. We wanted to expand on that history and dig deeper into the origins of US protest itself. Hallie hit on a general history, which encompassed a lot of current events, and voilà!

e: Lerner moved up the publication date in response to what’s happening as a result of the George Floyd murder. What’s been your reaction to the recent protests against police violence?

Marke: I live in San Francisco, a very small big city, where anything that happens can be felt by everyone. The protests have been so lively and engaging, surrounding my neighborhood, and we’ve had some looting as well. I have been absolutely fascinated by the creativity of the protests both locally and nationally, with childrens’ marches, skateboarders riding in protest, brilliant street art, and young peoples’ leadership. Much of the iconography is familiar from previous protests because, unfortunately, these incidents of police violence keep happening. But this truly has the feeling of a popular uprising, in which a broad spectrum of people participate.

Marke: It’s funny, but Into the Streets has been timely in more ways than one. The book was originally set for release earlier this year, but was delayed due to COVID. And then it was pushed forward due to current events. So it’s truly been sailing the crosswinds of recent history! That said, I did originally feel this book was going to be especially timely because of the upcoming election—now, with the conservative protests against the COVID shutdown followed directly by the current Black Lives Matter uprising, it’s feeling a little bit too on the nose! But in a broader sense, a book on the history of protest will, and should, always be timely because protest is one of our constitutionally guaranteed freedoms, and we should exercise it regularly.

Marke: This is such a great question. To begin with, these current protests are obviously huge but also broad, reaching into the smallest US towns and across the world. In this way they remind me of the 2003 protests against the invasion of Iraq, which were global protests that also occurred on very small scales throughout the US. They also remind me of the Great American Boycott or “Day Without An Immigrant” protest of 2006, which encouraged people who usually don’t protest to come out into the streets—in that case undocumented people and children of immigrants, in this current case people who have been moved by their own experience of discrimination and sympathy for others’ experience. Both of those protests remain among the biggest in American history.

There are also more direct correlations. As I pointed out earlier, these latest protests are more of a continuation of contemporary Black American-led protests, rooted in the 1960s Black Power movement and the Los Angeles uprising of 1992, and continuing through Ferguson in 2014. But protests against racial injustice and police violence stretch way back throughout our history, and quite a bit before the country was founded, as I detail in the book. The Boston Massacre was an instance of “police” violence which killed a Black man, Crispus Attucks. Protests against that murder helped spark the American Revolution.

Marke: Yes, definitely! I love protests of all kinds, the energy and the strategy—or even lack of either, which can be instructive in itself As a journalist, I get to cover many, and as a participant I get to go to many more. I was an out gay young person during the late 80s and early 90s, when I faced both the homophobic discrimination of the AIDS era and the very real possibility that my friends could be drafted for the Gulf War. It was also a great time of activism in the Black community, and I was fortunate to live in downtown Detroit. It was a very turbulent moment to be a college student. I discovered a voice and a community through organizing and political action. Today I’m just blown away at how much protests have grown creatively and as a natural part of our civic life.

e: What are some ways that protests don’t work? (i.e. a ’thumbs up’ in facebook) And what are some ways that do?

Marke: I think we have to first define “work” in terms of a protest. I think many people believe that protest must bring about immediate change, of laws or with other government actions. But there are so many other ways that protest can function successfully. On the most basic terms, a protest can make you feel like you’re not alone—others share your beliefs, and that simple affirmation can be so life-changing, especially in a country as large and spread out as ours. Even a “like” on Facebook can make someone else feel heard.

Going to a protest can also be a moral act. The giant marches against the invasion of Iraq didn’t cause the US to withdraw or change the government’s actions one iota, but just being there and speaking out is something that almost every participant looks back on and cherishes. (Some politicians wish they could say the same.)

All that said, I do often see a lot of energy and anger online that doesn’t always lead in the most productive direction. I think the Internet is tremendous in allowing so many more people to participate in protest, but I don’t think we’ve fully grasped its power to help or hinder real action and connection in the world.

e: Not everyone hits the streets to protest – what are some other ways people can make their voices heard or offer solidarity?

Marke: It’s a cliche, but money can really help! So many great causes depend on individual donors, and things like bailing protesters out of jail or supplying masks and hand sanitizer for protesters require direct contributions. It’s not the ideal system, but it’s the one we’ve got.

But beyond that—and so many of us are hurting for money and resources right now—I recommend direct engagement. Talk to your friends and family about the causes you believe in and what you see going on in the world. It can be very difficult and you can hit some brick walls! But while huge protests can bring about change, it’s often the hard, grassroots work of talking one-on-one and sharing information that helps the most. Listening is a great skill to hone, as well! Sometimes allowing people to say their piece is the best thing you can do, especially if they feel isolated or silenced.

Marke: Americans have an almost metaphysical belief in the power of free speech, and it’s hard not to feel optimistic overall about things if you trust in the idea, as I do, that free speech and assembly are essential to democracy, and that democracy is the highest form of government.

I like to think of the history of protest as one of evolving struggles—where the protest is really just the visible tip of an iceberg of cumulative action. The Women’s Suffrage Parade of 1913 was a carefully planned spectacle that gave a needed public push to decades of legal and individual agitation to win the right to vote for women. During the classic Civil Rights Era, images of well-dressed Black people beng firehosed and set upon by dogs helped change public opinion toward adopting the Civil Rights Act, but that idelible, terrible moment was just part of a tremendously coordinated strategy to enshrine and protect equal rights.

So we see that the public protest part is often really just the highly visible manifestation of an issue, it takes a lot of work behind the scenes. As long as people are doing the groundwork as well as showing up when needed, there’s the possibility for great change.

Marke: Yes! This is a book for young people, and it’s full of protests started by young people, from the schoolchildren of the 1963 Birmingham Children’s Crusade and the high school walkouts of 1968 Los Angeles, which launched the Chicano Movement—all the way up to Greta Thuneberg’s climate strikes and the Parkland school shooting survivors’ March for Our Lives. Here in San Francisco last week, 17-year-old Simone Jacques of Mission High School organized and addressed a 10,000-person George Floyd protest. Young people embody our eternal hope that we can change the world for the better. The fact that they continue to lead us on the biggest issues of our day fills me with tremendous hope for our future.

e: Is there anything else you hope people will take away from Into the Streets?

Marke: I hope young (and older!) people will read the book and see what a tremendous history of speaking out this country has. So much of this isn’t taught in schools—but as we see right now, we can’t avoid talking about what matters forever.