Read local musicians’ reaction to Shock G’a passing here.

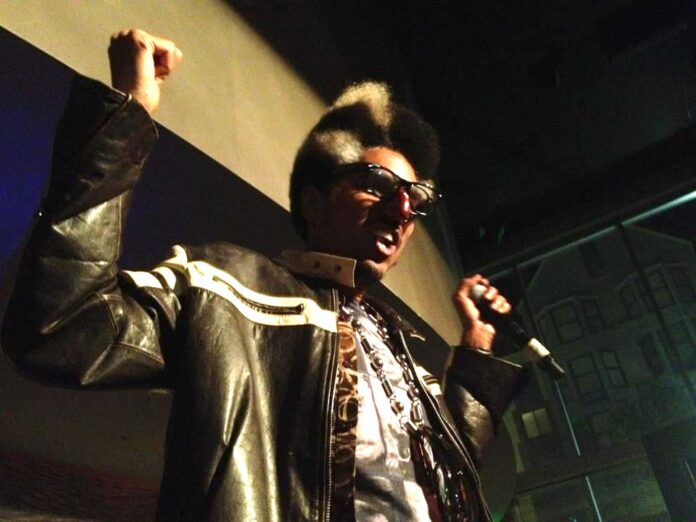

Though I only met him twice, Shock G, the Bay Area rapper who passed away last week at 57, shared a lot of insight with me, and I need to share what I can with you in hopes that you’ll look behind the Humpty nose and deeper into the music that he left behind.

Shock G was born Gregory Jacobs in Brooklyn on August 25, 1963 and passed away in his childhood city of Tampa on April 22, 2021. He moved to Oakland in the mid-’80s and spent the rest of his life making music in California, so we are claiming him.

Though best known for being the beloved frontman of Digital Underground, he should also be remembered for more than his turn in the pop music spotlight, which threw a bright light and warm glow on the best of the Bay Area in a way that hasn’t happened since. He was, and remains in spirit, an embodiment of the Funk. His personal musical icons thought so, too: George Clinton (who he collaborated with and sampled long before Dr. Dre and OutKast), Bootsy Collins (“He helped keep P-Funk alive!” he Tweeted of Shock on April 22), Stevie Wonder (who he sampled and introduced to the hip-hop world via 2Pac’s single “So Many Tears”) and Prince (who incorporated Shock’s beats into his 1998 Crystal Ball box set).

Like many Bay Area natives who were kids in 1990, Shock G and his alter ego Humpty Hump—two personalities who he took pains to appear completely separate entities, which fooled a lot of us for a long time—were friends in my head. Digital Underground performed at my very first rap concert at Shoreline Amphitheatre in Mountain View on August 24, 1990 as a support act for Public Enemy, the mighty East Coast rap group which had just released the album Fear of a Black Planet. Shock revealed in the 2004 documentary Digital Underground Raw Uncut that they made a huge financial sacrifice by taking that tour.

“We turned down a quarter million dollars to go out with [MC] Hammer to go out with Public Enemy for $150,000,” he said. “We took an almost double pay cut.” Hammer and En Vogue were worldwide stars representing Oakland, but Public Enemy was the best hip-hop group alive.

At 16 years old, I remember feeling pretty scandalized when Digital Underground took the Shoreline stage and started humping blow-up dolls. It was only years later that I learned that one of the backup hype dancers doing the humping was named Tupac Shakur.

Besides nurturing his talent, teaching him how to have a bank account and apartment, taking him on the road and producing seminal records for Tupac, I think of Shock G as the one who kept Tupac alive long enough for the rest of us to learn about him. And when I first met Shock in Los Angeles in 2004 to spend a whole day interviewing him about his only solo album, Fear of a Mixed Planet (a loving reference to Public Enemy), he regaled with tales of doing just that for Pac, from getting him out of a life-threatening altercation at that gas station on Van Ness in San Francisco to countless occasions of saving him from fights on the road after shows.

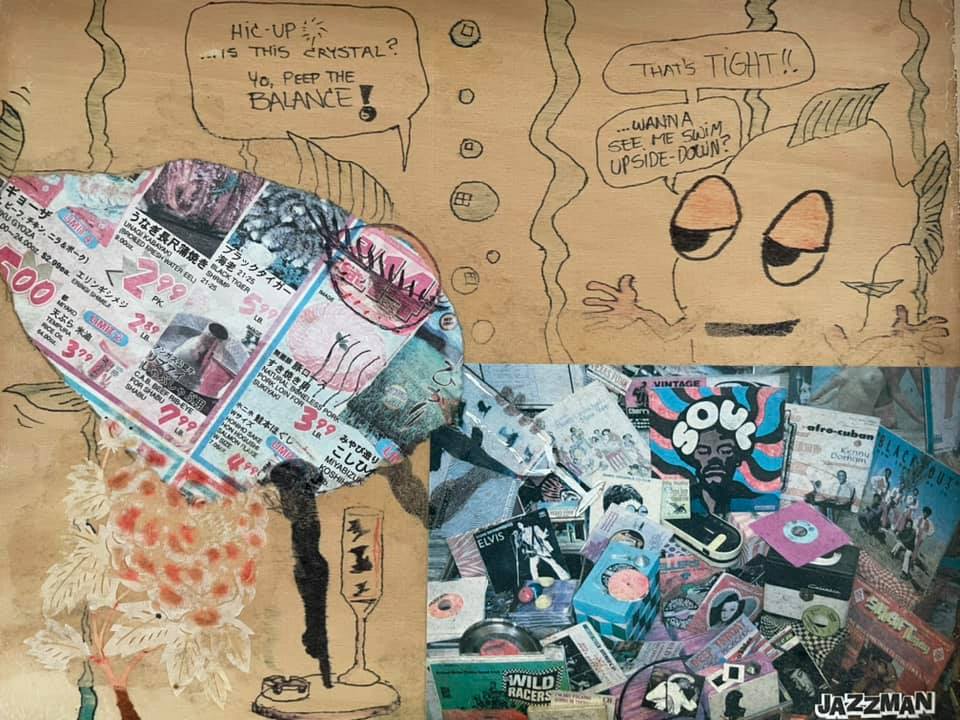

We also indulged in some arts and crafts while we chatted, and our collaborative piece pictured below shows the aquatic illustrative style made famous beginning from Digital Underground’s 1988 debut release, a local single called “Underwater Rimes.” In fact, the first few singles, released on Bay Area label TNT Records, sold so swiftly at the now-closed Berkeley record store Leopold’s that the shop informed New York’s Tommy Boy Records of the popularity and got the label interested in offering Digital Underground the recording contract that gave them worldwide fame.

Shock G was a musician with a deep reverence for music. He had a keyboard tattooed down the length of his right arm.

“I was a hunt & poke 1-finger player probably all my life whenever a keyboard was present, trying to figure out the popular melodies or whatever, but it wasn’t until I was 18 that I took a serious interest and began locking myself inside all summer practicing,” he told me in a followup email interview a few days after meeting him. (I left his ampersand-favoring punctuation in place, because it was so him.)

“I guess I taught myself, but I was like a sponge for any tips or help from other musicians, teachers, records and books, anything that helped me grasp it and furthered what I knew. Before that I was a drummer in funk bands (age 11 to 13), a DJ & emcee (14 to 17).”

The rhymes started flowing in his early teens: “A basic battle rap about rockin the mic was probably the first thing I ever authored musically when I was around 14,” he revealed.

It wasn’t only audiences at live shows around the world who found out that Shock was great on the keys, where his charisma and improvisational skills truly shone—if he saw a piano in a hotel lobby or basically anywhere, anyone nearby learned about his talent, too. I wanted to know why that remained his instrument of choice.

“After dabbling with other instruments I was drawn to the piano for the huge spectrum it offered, you can do bass, chords & midrange melodies, and upper melodies all at once which allowed whatever you played to be recognized even more than say, a bass or horn which only allowed you to do one part at a time,” he wrote. “So if I was the only musician in the room I could still play stuff for people in its entirety. I also realized that with the new technology a person could do the drums from a keyboard as well as deejay due to sampling. And by the mid ‘80s most synthesizers could imitate all the other instruments, so it became the ultimate music production tool. The keyboard player was like the quarterback of the music game and I enjoyed having that control.

“A whole separate reason that counted just as much was the sheer beauty of the instrument in sound, grace & appearance,” he continued. “The piano always had sex appeal to me and to other people too I noticed. And finally the physical popularity of it attracted me as well, meaning that they seemed to exist everywhere, in homes, schools, hotels etc, and unlike other instruments, it doesn’t require electricity which makes it easy to pursue. And it wasn’t so loud as drums & horns so it was more welcome on the social scene. And oh yeah, unlike horns, your mouth is free to speak, sing, rime, take a drag, or sip a drink. So is your other hand when you need it, unlike any of the other instruments.”

For a deeper understanding into his musical mind, it’s helpful to know about the past and present players who caught his ear: “Oscar Peterson, Thelonious Monk, Erroll Garner and Herbie Hancock were my favorite blues & jazz pianists, all of whom I would imitate while I was learning. I used to copy Ray Charles a lot too for my right-hand blues movements, his blues piano was SO dirty & rugged. Bernie Worrell and Walter ‘Junie’ Morrison (George Clinton & P-Funks 2 primary keyboard players) were and still are my all-time favorites for popular music. These days some of my favs are D’Angelo (especially on organ), Fiona Apple, Amp Fiddler and the keyboardists for The Roots and The Pharcyde. And oh yeah, Sylvester Stewart a.k.a. Sly Stone was a monster on the keys too for my tastes.”

If you only know “The Humpty Dance” and “Doowutchyalike,” do yourself a favor and check out Fear of a Mixed Planet, which was therapeutic for Shock to release. At the time, I asked if he ever went through an adjustment process of having to reclaim music as his art and not commerce after the meteoric pop music years.

“Definitely,” he replied. “Touring with d.u. and/or other paid appearances, and doing paid studio sessions is the 9 to 5 that gets our rent paid and families fed. But it’s such a routine that there’s little room for any new in-the-moment artistic expression. Here I am in my 40s but people still hire me to be who I was when I was 25, both mentally & politically. Can you imagine how frustrated & trapped that makes me feel as an artist? Fear of a Mixed Planet was straight up therapy for me, without it I may have just given up completely. (Tears of a clown basically.)”

After his solo work was out in the world for a little while, I wondered if he felt more comfortable and confident in his skin as far as expressing his musical personality of him in his 40s rather than staying forever 25.

“No doubt,” he said, “I can let go and let music & art flow from me freer now without a lot of emotional baggage and anxiety about not being fully heard or understood. Mixed Planet got a lot off my chest and sorta cleared my soul, set the record straight in terms of my personal perspective, my true love & appreciation of life, the world, the universe.”

Fear of a Mixed Planet used lighthearted wit and humor to question how hard and serious hip-hop had gotten — ”Enough keeping it real, we can still keep it beautiful,” he insisted on “Keep It Beautiful,” the song that opens the album.

“Historically African tribes, native Americans and many other cultures used to have weekly rituals in which the entire town or tribe danced & sang together to celebrate another week of precious life on Earth,” Shock wrote to me. “Everyone in the entire city would be involved, young or old, and people were assigned that which came most natural to them whether it be dancing, singing, or playing an instrument. Nobody was the ‘star,’ it was a community thing with perhaps a designated ringleader or conductor.

“It wasn’t until European culture took over, and capitalism & industrialism dominated the world that we all adopted this serious & so-called ‘civilized’ outlook in which it’s ‘better’ to be concerned with business & security than it is to be joyous, earthy, and to dance. Some of us still prefer the original way as a survival mechanism for the human spirit, and it’s my life-long duty to our universe (and to life in general) to fight for those almost forgotten human qualities. We must never lose our hope, our love, our joy, and our appreciation of life itself. We must never surrender to fear, or allow it to limit our focus to violence & hate.”

When I met Shock, I was working on a book about Southern rap music, and he mentioned that he wrote a lot, the fruits of some of which ended up on his now defunct website, which was called the Gate. I saw the eloquence in his email interview responses and after he wrote publicly about his intent to retire a few months later, I asked him if he might want to put together a book of some sort and offered editing and structural help. Though I failed to coax him into doing anything officially, there’s anecdotal evidence that he did later work on books and book ideas privately, some of which fell victim to computer data loss in recent years.

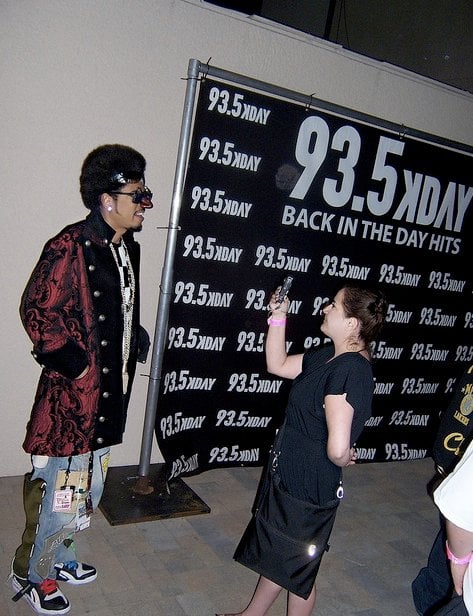

I last spoke with Shock backstage at Krush Groove 2011, a series of old-school hip-hop concerts held by Los Angeles radio station KDAY. You’ll be able to see his earnestness in wanting to stretch his creativity as well as his onstage humor in the short Krush Groove clip below.

I last saw him perform live with Money B as Digital Underground at a Black Panther benefit celebration in honor of what would have been Tupac’s 41st birthday at the now shuttered Yoshi’s in SF in 2012. It wasn’t billed as their last live appearance together, but that’s what it ended up being; with Shock’s consent, Digital Underground continued on performing live shows with a replacement known as Young Hump. George Clinton, nearly unrecognizable without his rainbow-colored long hair, surprised the crowd by joining his “Sons of the P” onstage for that last show. How fitting.

“Don’t take yourself so seriously and allow the bigger simpler messages of nature [to] flow through you,” Shock wrote of the best musical advice he ever got from Clinton. “In the studio George taught us to allow it to happen, encourage the best of the people around you, and then just trust it, sit back & watch it grow. Incorporate everything life throws at you into what you do, and don’t block the magic. The magic is in the variety, the hookups, the unexpected. Trust the simple & plain, the weird, the different, the fun, the goofy, the nasty, the funk; trust life.”

Rest easy, Piano Man. And trust us; we’ll keep your musical soul alive.