By the time budding movie director Drew de Pinto moved to the Bay Area in August of 2020, they had missed last call at San Francisco’s bars and clubs—by five months.

The city’s nightlife scene had been paused to curb the spread of COVID, so the venues’ owners and caretakers were struggling to stay afloat.

San Francisco’s queer community—long reliant on these establishments not just to drink and dance but also to be themselves and form a community—was hit particularly hard.

So when it came time to create their first short for Stanford’s Documentary Film MFA program, de Pinto—interested in the ways nonfiction and experimental modes of filmmaking can inspire better worlds for trans people—decided to spotlight three vital LGBTQ+ venues that were in danger of shutting down for good.

Hearing that The Stud had already closed, de Pinto started there and later learned of two other trans-friendly businesses in danger of being next—El Rio and Aunt Charlie’s. (The Stud announced this summer that it had found a new location and will reopen in 2024.)

Working with fellow student and producer Azza Cohen, de Pinto spent two weeks filming in and around these venues that fall, learning about their illustrious pasts and current hardships.

In discovering and documenting the queer histories of these storied sites for what would become Last Call, de Pinto found hope. Many of the patrons of these spaces had overcome so much over decades—police raids, the AIDS pandemic, and gentrification—so there was no reason to believe they couldn’t survive COVID. Their optimism colors the experimental short, which weaves archival and contemporary footage together with the hope that these venues would eventually return to their former glory.

After screening at the Mill Valley Film Festival, SF Queer Film Fest, and SF IndieFest, Last Call plays the 26th edition of this week’s San Francisco Transgender Film Festival (SFTFF) on Wed/8 as part of a shorts program at the Roxie Theater. It also screens online from Sat/11-Sun/19.

I spoke to de Pinto about making the film, finding hope in San Francisco, and the power of queer resilience.

48 HILLS How did you select the three venues to profile?

DREW DE PINTO I heard a lot about how difficult it was for smaller, independent venues to get the funding that they needed and also the lack of support for service and nightlife workers. A lot of my films are location-based, so the first thing I did when moving to the Bay Area was reach out to trans performers, and everyone pointed me to The Stud, which had recently closed.

I watched a livestream of The Stud’s funeral, which affected me. It represented this world of radical queer and trans community—particularly, given its history as the first worker-owned nightclub in the country.

So the original idea was to make the film about The Stud. I wanted to shoot the empty interiors and end with this recreation of a performance, but we couldn’t figure out how to get into The Stud’s old venue. So it was through talking to a lot of The Stud Collective members and other performers associated with the space that I learned about Aunt Charlie’s and El Rio, which were two similarly beloved and historic queer venues that were facing unknown fates in the pandemic. That’s how it came to be what it is.

48 HILLS What was it like to film at these empty bars and clubs?

DREW DE PINTO Of course, I couldn’t film at The Stud because it was closed, but I spoke with worker-owner Vivvyanne ForeverMORE. My first encounter with El Rio and Aunt Charlie’s was shooting in these empty spaces with just one caretaker. At El Rio, it was bartender Cynthia Martinez and at Aunt Charlie’s, it was manager Joe Mattheisen.

It was beautiful, in a way. I talked to Joe for hours about [late drag performer] Vicki Marlane and the history of the space. He had been there for decades, so I got these amazing experiences in those spaces via one-on-ones with the bartenders and the managers.

My first experience in San Francisco nightlife was shooting these empty venues and searching archival footage, particularly of the High Fantasy show at Aunt Charlie’s. They had a beautiful museum exhibit called High Fantasy Memory Index, featuring videos, photos, and writings about this trans-performance-art drag show, High Fantasy.

I went through all this archival footage and saw these spaces when they were alive and thriving and spent time in the empty venues. So it was a very backward experience of San Francisco nightlife because then, as I stayed there for two years, I ended up going to a lot of parties at El Rio and shows at Aunt Charlie’s and getting to see these spaces come back to life.

48 HILLS What was the general mood of these three caretakers when chatting about the closures?

DREW DE PINTO There was a sense of mourning with The Stud because it had recently been saved from closure a few years before when The Stud Collective came to be the first queer worker-owner co-op club. And then, it closes. There was still a sense of hope for the future. But it was clear that it would be a long, difficult road to reopening—if that were to happen.

El Rio had also recently been bought by a nonprofit, so they had more confidence about reopening. But the venue that was the most unsure of its immediate future was Aunt Charlie’s. They had, at the time, a crowdfunding campaign going. But Joe seemed very uncertain.

He went there every day just to spend time because it was something to do, somewhere to go. He would make his coffee, watch TV, and clean the bar—and was excited to talk about the history. But he seemed very unsure. He was very proud of the community support that was rallying around Aunt Charlie’s but also frustrated that they weren’t able to get a grant from the government that they had applied for because the venue was physically too small. So there were a lot of different tones and feelings.

48 HILLS El Rio and Aunt Charlie’s are back, and The Stud will reopen at a new location next year. Knowing this now, what does this film say about queer strength?

DREW DE PINTO Something important to me in making this film was the very long, storied histories of resilience and precarious survival that all three of these venues had long before the pandemic. El Rio started as a Brazilian leather bar. You can trace Aunt Charlie’s origin back to the ‘30s. They all have long, storied histories of precarious survival—and the pandemic was another moment where there was so much uncertainty and loss.

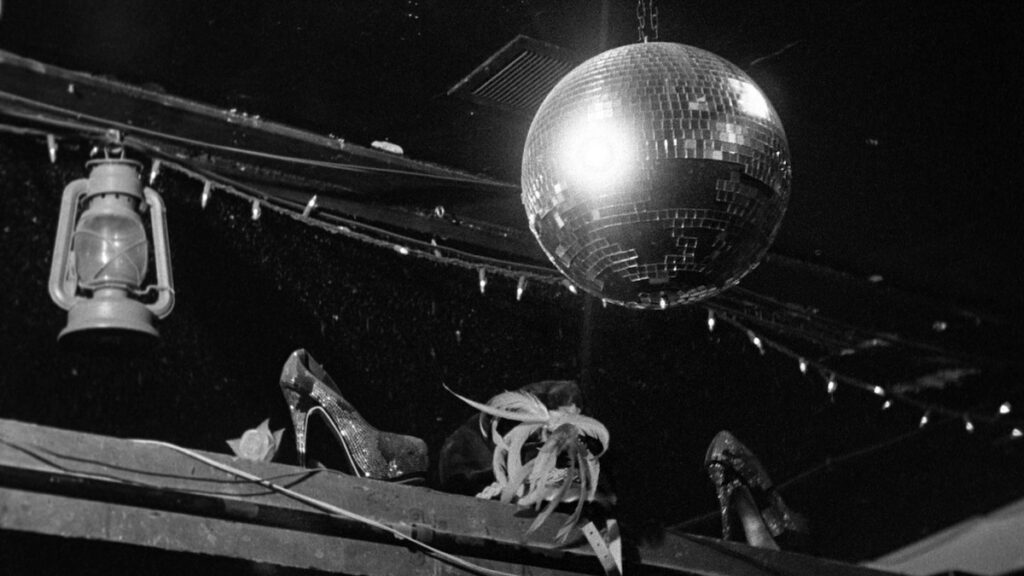

And although the film starts with a funeral and has a lot of mourning, I’ve always thought of it as a testament to queer resilience and immortality. Using colored digital footage for the archival and black-and-white 16mm film for the current, I was trying to play with ideas of linear time and progress and think about how through all of these storied histories and constant threats to queer spaces, these communities always find ways to live on.

48 HILLS Now that you live in New York, what’s it like for you to come back to the city for an event like SFTFF?

DREW DE PINTO San Francisco has become an important part of my life. I grew so much as a person, a trans person, a queer person, a filmmaker, in the two years that I was in the Bay Area. Also, I started getting to know San Francisco in 2020, when it was empty and learned a lot about its history. I got to see it come back to life in a beautiful way—and also, the queer and trans community flourish and get creative in finding ways to unite in solidarity. So I always feel a lot of hope and strength in San Francisco and also a lot of connection to queer and trans history because I learned so much about it in San Francisco. It was the first time that I was able to have long conversations and connections with people like me in the past. And it was San Francisco and its history that allowed me to imagine myself and people like me in the past. That gave me more hope for imagining a future. I’ll always draw a lot of strength and hope from that.

Last Call Wed/8, Roxie Theater, SF. $15 suggested donation. Tickets and more info here.

For more on SFTFF, click here. See Dennis Harvey’s SFTFF guide here.