“The word ‘whore’ is used to stigmatize anyone that doesn’t fit the criteria of a good girl,” Margo St. James said, decades before her death from complications of Alzheimer’s disease at 83 on January 11 in a memory care facility in Bellingham, Wash.

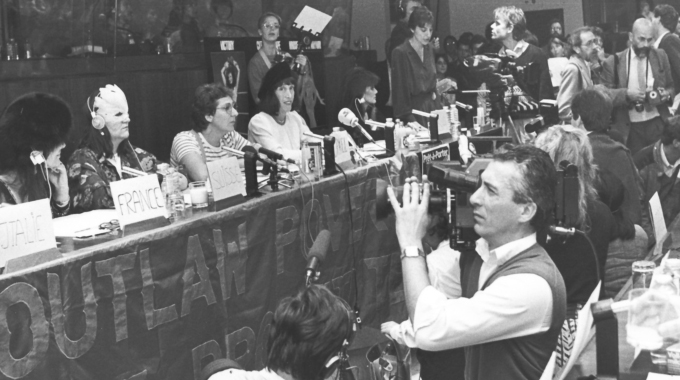

“She could be overweight, she could have dropped out of the church, she could have gotten a divorce in the ’50s, she could talk back or talk bad, dress wrong, hang out with the wrong people, things like that,” St. James continued, as captured in Carol Leigh’s 1991 documentary Outlaw Poverty, Not Prostitutes. “So really, the word ‘whore’ is still used to keep other women in line, all women. But the punishment of the prostitute is the example set by the system.” [Note: Many modern day advocates eschew the term ‘prostitute,’ and prefer to use ‘full service sex worker.’]

St. James’ boldness, and her success in connecting widely varying individuals in the struggle for sex worker, queer, and women’s rights, will be under consideration Tuesday when the San Francisco Board of Supervisors votes on declaring February 14th, 2021 “Margo St. James Day.”

Life circumstances, political acuity, and a gumption that seemed improbable, unconquerable, endless contributed to St. James’ legacy. In death, she leaves us with the Tenderloin’s beloved St. James Infirmary, and memories of her near miss in 1996 at becoming a SF supervisor. She left her mark on several areas of activism.

“Because I’ve been involved in the sex-positive movement, the queer movement, and the sex workers’ rights movement, I think about Margo as an inspirational figure in all three, though we don’t always talk about them together,” wrote Carol Queen, PhD, co-founder and director of the Center for Sex & Culture, to 48 Hills.

Queen continued:

Margo’s work was so crucial to our right to bodily autonomy—one of the sex workers’ mottos back then was “My body’s my business,” and you can read that several ways! Her work made space for sex workers to ply their trade, obviously, but she tackled shame at the same time. Her focus wasn’t just political or rights-based, though it was incisively both of those, but also about making cultural space. As I’ve said many times, the Bay Area (and the way we think about sexuality overall) wouldn’t be the same without her work and her example. She was a hero of several revolutions.

Where did the St. James revolution begin? In the same place it ended; Bellingham, where she was born on a farm in 1937. Like many women of her era, St. James married her high school sweetheart shortly after graduating. He was a commercial fisher, and they had a son. St. James left them both in 1958, when she moved to heart of beatnik San Francisco to focus on her painting career, living first in North Beach and then Haight-Ashbury.

Her arrival to the sex worker movement was distinct. In her preface to A Vindication of the Rights of Whores by Gail Pheterson (a feminist writer, educator, and lover), St. James writes that she “decided” to enter the world’s oldest professional after she was swept up in a 1962 sex worker raid. A San Francisco judge told her that she was a sex worker, reportedly based on the fact that St. James knew the terminology of the trade.

That ire she felt over that arrest sent her to law school. St. James never graduated, but gained enough legal knowledge to successfully appeal her conviction, work for criminal defense attorney Vincent Hallinan, and become one of the first woman private detectives in California.

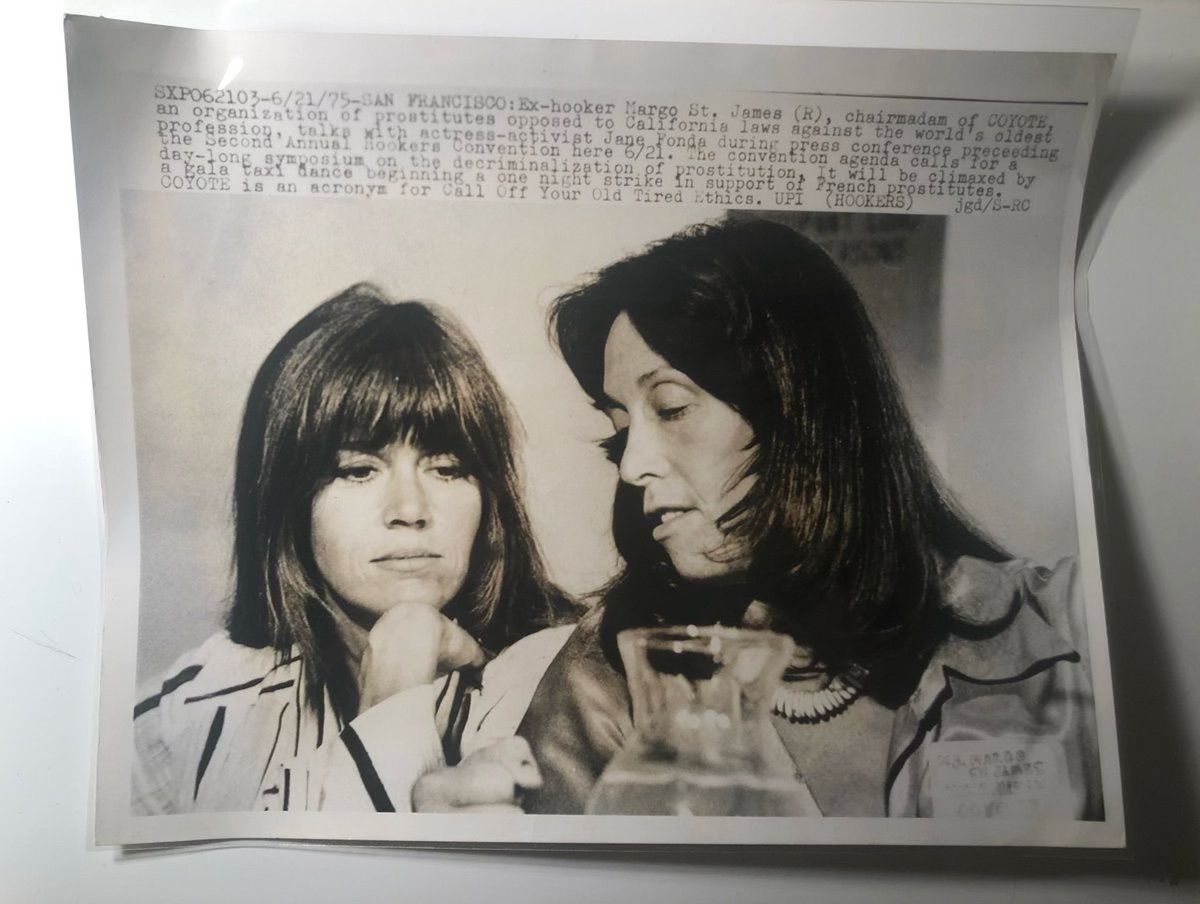

By 1972, the politicized St. James was holding the first meeting of her group Whores, Housewives, and Others (WHO) on a Sausalito housebout. Then came the 1973 founding of Call Off Your Tired Ethics (COYOTE). COYOTE received an early grant from Glide Memorial Church, which also hosted the 1974 National Hookers Convention.

“She always knew what was going on in SF more than anyone else,” Molly Bode (née: Rodriguez), COYOTE’s secretary, wrote to 48 Hills.

St. James formed a unique social circle made of her fellow sex workers, lawyers, journalists, and politicians, appearing regularly in Herb Caen’s Chronicle column. She even mingled with cops, like San Francisco’s Sheriff Richard Hongisto, who reportedly told her that police abuse of sex workers would only stop if someone from “the victim class,” as he reportedly put it, spoke out.

The activist was happy to be that person. St. James fought valiantly against cop harassment of sex workers, the use of condoms as incriminating evidence, and mandatory jail STD testing and even quarantining. COYOTE offered legal aid to sex workers.

Her message was spread nationwide by COYOTE Howls, a newsletter filled with news for and by sex workers that was published from 1974 to 1979. One copy landed in the hands of a young Annie Sprinkle, who would become a feminist pornography icon—but who at the time had been working in New York City massage parlors for two years.

“[I’d] never once heard anyone ever mentioned the idea of decriminalizing prostitution,” Sprinkle recalled in a Facebook post paying homage to St. James. “It seemed like magical thinking, a far-fetched, absurd idea.”

“When Margo spoke she was low key, calm, cool, and collected,” Sprinkle continued. “But by the end of the meeting we were all ready to work to rid the world of the bad laws against our profession and to help relieve the stigmas and stop the dangers of being a whore. Over the years I went to every event Margo did that I could, because they were about the liberation and empowerment of people like me.”

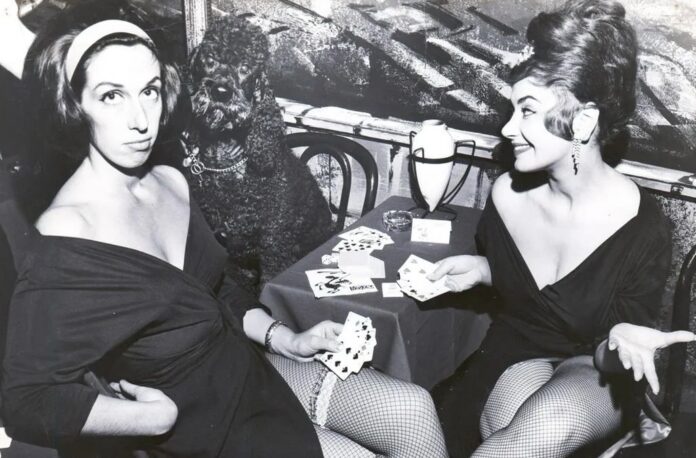

Along with WHO, St. James helped to organize the annual COYOTE fundraiser the Hookers Ball, which at its height in 1978 brought 20,000 attendees to the Cow Palace. St. James arrived at that year’s ball on the back of an elephant.

In 1980, she pulled one of her wildest capers to date, running for the Republican presidential nomination.

“If I remember correctly, she picked the Republican party to startle as much as anything, which was part of her brilliance as a wall-breaker,” St. James’ “right hand” Priscilla Alexander told 48 Hills.

After meeting Gail Pheterson, the two organized international gatherings of sex workers, building to the World Whore’s Congress, which took place in Amsterdam in 1985 and the European Parliament in Brussels in 1986. Attendees spoke of how to protect themselves on the job in the thick of the HIV/AIDS crisis, and drafted the World Charter for Prostitutes’ Rights.

By then, the Reagan years’ “conservative swing in the States” and formidable anti-pornography movement led her and Pheterson to move to the south of France and the Netherlands.

St. James moved back to the US in the early ‘90s, eventually settling on Orcas Island in Washington State. After her unsuccessful run in 1996 for the SF Board of Supervisors (her unforgettable campaign slogan—a brainchild of longtime associate, the former member of US Congress and chairperson of the California Democratic Party John Burton—”The Lady is a … Champ”) came the 1999 birth of one of her most significant contributions to the Bay Area, the St. James Infirmary.

“None of us knew exactly what we were doing in creating the first occupational health and safety clinic for sex workers in the United States,” co-founder of the Exotic Dancers Alliance and founding executive director of St. James Infirmary Johanna Breyer told 48 Hills. “But Margo possessed enduring confidence and determination, so we just followed suit, because ‘in Margo we trust.’”

Today, St. James Infirmary provides sex workers with everything from mental health and peer counseling to hormone therapy, needle exchange, and primary health care services.

Breyer counts St. James as one of her mentors, and “the patron saint of sex work,” and furthermore:

Margo St. James was an original BOSS—a no bullshit and no holds barred lady, a social butterfly with an amazing laugh and wild sense of humor, and a fierce advocate for sex workers for decades,” Breyer says. “But above all else, Margo was generous and kind, a simple farm girl with a revolutionary mind, who was always willing to help those who were mistreated or struggling.

Supervisor Rafael Mandelman introduced the resolution to declare February 14th Margo St. James Day, “in memory of a truly extraordinary woman who dared to champion the cause of sex worker rights, who fought fiercely and effectively for women’s liberation, and who in doing so changed not just our city but our world,” Mandelman says.

“Margo was one of the great San Franciscans of the last half century.”