A proposal that could rival the forced relocations of the discredited Redevelopment Era is headed for City Hall approvals — with very little news media scrutiny

By Tim Redmond

DECEMBER 21, 2015 — Under the guise of creating more affordable housing, the Mayor’s Office is proposing a plan that could lead to the greatest wave of displacement since the Redevelopment era of the 1950s. And other than excellent stories from People Power Media and sfbay.ca, it’s gotten very little in-depth news media attention.

The program is called the Affordable Housing Density Bonus plan, and it has its roots in both state law and a 2013 court decision in Napa County.

But in the end, this will be a local decision – and the plan is almost breathtaking in its scope. It is, critics say, a return to the failed policies of an earlier era, when tearing down homes and businesses in the name of improvement was official federal, state, and local policy.

“No matter how you look at this, it’s the Redevelopment model,” said Peter Cohen, co-director of the Council of Community Housing Organizations. “And that model didn’t work.”

A careful analysis of the proposed bill, which is still getting revised, shows:

- More than 30,000 units of housing – and all of the corner stores, restaurants, and community-serving small businesses located on the first floors below them – are potentially targets for demolition. The law encourages property owners to turn smaller buildings into bigger ones by adding stories – and the only practical way for that to happen is if existing buildings are torn down.

- The plan put tens of thousands of units of rent-controlled housing – the most important affordable housing in the city for working class and middle-class people – at risk. In a flashback to the worst era of Redevelopment, the planners say people thrown out on the streets when their homes are torn down would have the right to return later – but there’s no clean plan to give them affordable homes in the meantime, and all the evidence shows that “right of return” doesn’t work: Tenants who are displaced for years wind up leaving the area forever.

- The right to construct taller buildings doesn’t really create much in the way of new affordable housing, since the developers can count the replacement units that were there in the first place toward their “affordable” responsibility.

- The new taller buildings will be able to block sunlight in any existing back yard, as long as it isn’t a public park. For those tens of thousands of San Franciscans who use their small yards to grow gardens, to sit outside, to have barbecues … there is no protection from construction that ends your access to sunlight.

- Oh, and the new rules would pretty much end public input into neighborhood planning, since most of the new projects would be exempt from the normal hearing and appeal process.

- There is no credible process to protect existing small neighborhood businesses from wholesale displacement, meaning the plan could transform dozens of local commercial districts.

It’s a gigantic change in planning policy, driven by the idea that the city of the future has to be built by destroying the city of the past. In essence, the proposal is aimed at making San Francisco a better, and possibly more affordable, city for people who are going to move here in the future, at the expense of existing residents.

“It’s a demolition and displacement machine,” longtime housing advocate Calvin Welch told me.

The proposal has its roots in state law, a 2013 court ruling, and the desire of Mayor Ed Lee to build more affordable housing without putting out more public money.

In essence, the idea is to allow developers to add as many as two stories above what current zoning would allow if they agree to provide additional affordable housing.

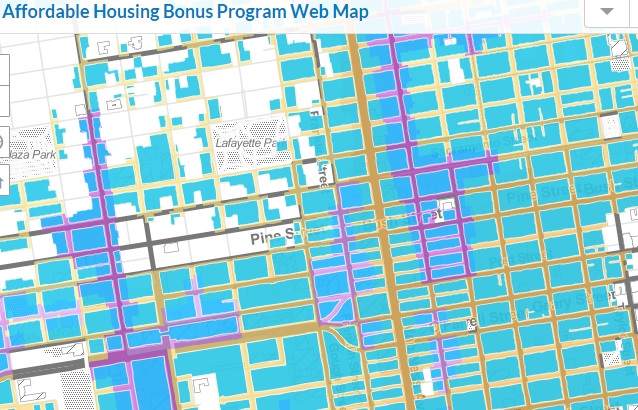

The number of parcels involved is massive, and includes much of the eastern side of the city and large swaths along transit corridors on the west side.

But the actual levels of affordable housing that would be added are fairly minor. The city’s plan would allow the “bonus” – which also includes concessions for larger bulk, smaller backyards, and less parking – if 30 percent of the units are “affordable.”

But the city already requires 12 percent affordability, and that number may go up next year, as both the Mayor’s Office and some supervisors are talking about increasing it. So it’s an extra 18 percent – and that can be so-called “middle income” housing.

“Most of the housing,” a set of questions posed by the Council of Community Housing Organizations notes, “will be studios and one-bedrooms priced for individuals earning $86,000 to $100,000 a year. … By comparison, a [San Francisco public school] teacher earns between $49,000 (entry) and $68,000 (after ten years).”

Potentially, some of the housing could go to people with incomes as high as $150,000 a year. So the developers aren’t losing all that much in exchange for their increased density.

In its presentations to the Planning Commission and the public, the Planning Department points to a number of “soft sites” that would benefit from the program. Those are lots that are currently vacant, or have old gas stations or other uses that are increasing converted to housing.

But there aren’t 30,000 soft sites left in the city, so the vast majority of the places eligible for this bonus are places where there’s already existing housing. Which means that for the program to work and create new housing, many of those buildings would have to be torn down and replaced with larger ones.

And in nearly every case, there are people already living in those buildings.

So one of the key elements of this proposal centers on how you deal with the inevitable displacement of thousands of current residents.

I asked the Planning Department’s spokesperson, Gina Simi, to explain how the legislation would protect existing tenants. Her response:

There are several additions to the requirements that are still being determined. However, in all cases, the rent control unit would be replaced by a [Below Market Rate] or permanently affordable housing unit that is monitored by [the Mayor’s Office of Housing and Community Development] — as are all existing inclusionary units. Income qualified tenants would be charged no more than 30 percent of their income for housing.

That’s a fascinating approach that is very different from current rent-control policy (and it’s an interesting twist on the idea of building housing for the “middle class.” Rent control in San Francisco has never been means-tested. BMR housing is restricted to people who earn within a certain band of income: Too low and you don’t qualify as able to pay the rent, too high and you are ineligible.

So, for example, if rent-controlled units occupied by middle-class families are replaced with BMR units, those families might not qualify to move back into their own homes.

And there’s nothing in the plan that addresses the size of the new units. Developers would be encouraged to build a certain percentage of two-bedroom units, but those apartments could be far smaller than the existing apartments.

Sup. London Breed told me she has introduced an amendment that would exempt rent-controlled housing from the program for one year, while Planning studies all of this. (UPDATE: The amendment, her office says, would apply for one year or until Planning and the Supes adopt a plan to protect rent control and existing tenants). But in the long-term, it’s a key piece of the puzzle: If rent-controlled units are off the table, the plan would be a lot more palatable to tenant groups, but would also be far more limited in scope.

In earlier discussions, Planning talked about requiring that rent-controlled units be replaced with new rent-controlled units. That’s not going to work: State law bars rent control in buildings constructed after 1979, and besides, unless the city found a way to ensure that the new units were rented at the same rent as the old ones (again, state law doesn’t allow that) the new units would start off at market rate.

Then there’s the problem of housing existing residents during the period (likely of at least a year) while the old place is torn down and the new one is built.

The record of past redevelopment efforts is clear: Most displaced residents are never able to move back. In fact, if you’re living in a rent-controlled place today, and you have to move out while it’s being rebuilt, it’s almost certain the you won’t be able to afford temporary replacement housing anywhere in the city.

How does the city plan to address that? From Simi:

As drafted, displaced renters would be afforded the same relocation benefits that currently exist.

The law says that a building can be torn down and the tenants evicted with nothing more than “proper notice” to those residents.

However, she said,

the Department has been working with tenant advocates to explore ways to enhance these benefits, including:

right to return

required relocation assistance – i.e., requiring that the Project Sponsor help locate a new unit for the household

relocation costs and rental assistance

The current version includes only existing relocation fees, which are only a few thousand dollars and would barely pay for a moving truck, much less the first-last-and-security requirement for a new apartment.

Right to return is nice – but not if the tenants are forced to move out of town, and out of the region, find new jobs, and resettle in another community because they are priced out. And asking the project sponsor to “help locate a new unit” is pretty much a farce as long as those units, at the price existing rent-controlled tenants are paying, don’t exist.

So that brings up rental assistance – and it would have to be a large amount of money. Sup. David Campos tried to get that kind of assistance for people facing Ellis Act evictions, but the courts threw it out.

Let’s take, say, a family of four living in the three-bedroom flat in the Mission, or Noe, or the Castro. They’ve been there 20 years, and are paying $2,000 a month rent.

Demolish that unit, and even if you did build a 3BR replacement (and very few of those will be built) where would that family go for the next year? The kids are in school here, and the parents have jobs here, and they’re part of the neighborhood and community – and a comparable place would be at least $8,000 a month at current rates.

Will the developer pay the $6,000 a month difference for the entire time of construction? That’s around $75,000. Will the courts allow that?

You see the problem here. There’s really no credible way to “relocate” tenants who are paying (and can only afford) well below market rates while their homes are torn down and rebuilt.

Let’s run the housing-benefit numbers. Take a three-story building with three flats, all under rent control. Let a developer turn it into five stories, of mostly smaller units; say you wind up with ten apartments instead of three.

The developer has to provide 30 percent affordability – but replacing the three units that were torn down counts toward that number. So all that builder has to do is put the existing number of affordable units into the building, and he or she gets seven new market-rate units in exchange.

That’s not an affordable housing density bonus. That’s a market-rate housing density bonus.

Simi told me that “the Department is looking into changing the requirements for the local program so that [replacing the existing units] are supplemental to the required percentage of affordable housing.”

If that doesn’t happen, the whole thing becomes something of a bad joke.

There’s another problem with demolishing buildings along transit routes and in central neighborhood corridors: Most of those areas have existing small businesses on the ground floor.

Among the areas where the new rules would apply are 23 neighborhood commercial districts.

There is no commercial rent control in California. There’s nothing in this law or state law the protects small businesses who face displacement – and for many, “relocation” is a death sentence.

You can’t relocate a neighborhood hardware store, or café, or corner market; they rely on the foot traffic in the existing neighborhood. Most of these businesses aren’t destination shops; move them out of their community and they lose their customer base.

And, of course, the types of older, smaller (and cheaper) properties that these businesses inhabit will likely be replaced with bigger, more expensive places that will attract an entirely different type of business.

So this could be brutal for neighborhood merchants – a constituency largely overlooked in the discussion so far.

The other thing this law would do is limit the ability of the public to demand a hearing on or object to demolition-and-replacement in many cases. Only where there are “voter approved” neighborhood plans would developers be required to come before the Planning Commission for a hearing. In most cases, getting a permit to build a taller edifice would be nothing more than a staff decision – that is, you show up at the Planning Department with the plans your architect signed off on, you pay your fee, and you get a permit.

Demolishing existing housing would require another permit – but that already happens all over the city, and has been happening (on a much smaller scale) for years. And remember: This entire program becomes nothing more than a minor deal resulting in a few hundred units a year unless existing property can be torn down on a massive scale.

Yes, if this plan goes forward and works the way the mayor and the Planning Department are presenting it, more housing will be built in San Francisco. Much of it will be beyond the reach of current residents, and many will be forced to leave – but new arrivals with high-paying jobs will have more options.

Property owners will have, Welch told me, “a huge incentive” to tear down rent-controlled buildings, since the potential profit will be high. (Again, think of our three-flat building that’s been under rent control for many years. Turn that into ten apartments, seven with no rent control, and the monthly income soars.)

The forced relocation of thousands of tenants, from all parts of the city, could totally transform the demographic makeup of San Francisco, on a scale that dwarfs what’s been happening in the past five years. It’s hard to imagine that the drafters of this law were unaware of those impacts.

Which raises the question: Is that really what they want?

The measure will come before the Planning Commission Jan. 28.

Please support us so we can continue calling attention to issues like these.