I keep having to correct Chuck Nevius, and this time, he’s going on about the glories of the Google buses, quoting Sup. Scott Wiener, who loves the private the shuttle program.

Nevius insists that

Actually, the supervisors have no authority over the shuttle buses, which are regulated by the MTA. The supervisors may pass a resolution of some kind, but as one insider put it, they would be passing “a non-binding resolution in support of a tentative agreement over which they have no jurisdiction.”

That’s not at all true and misses the entire point of the discussion that’s going on here. Even Wiener, who really really supports the current plan, recognizes what’s at stake.

First of all, the supes do, indeed, have control over things like bus stops, and zoning – and the environmental impacts of traffic projects, which is why the pilot program to allow the Google buses to use those stops required Board of Supes approval.

Now the issue before the board is an appeal by labor and environmental groups of the decision that the full project can go forward without an environmental review. Wiener doesn’t think there’s a legit environmental issue here, but he also knows that if six supervisors vote in favor of the appeal, the program as it now exists will be at the very least suspended and possible eliminated or altered in a major way.

The city would have to study, for example, whether the tech shuttles have driven displacement.

Nevius insists that “the buses don’t create housing demand any more than a rooster crowing causes the sun to rise,” but there’s plenty of evidence that he’s wrong.

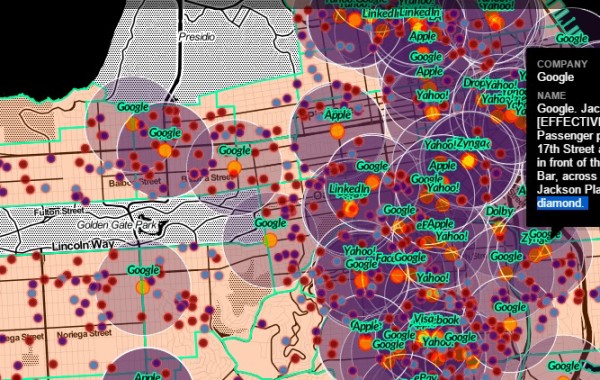

In fact, several people testified before the board that 60 percent of all no-fault evictions in the city have taken place within four blocks of a tech shuttle stop. Even Wiener, at the last board hearing, in effect admitted that new sources of convenient transit drive up property values; if they put a new BART station at 30th and Mission, near where I live, people who work downtown or in the East Bay along BART lines would have additional motivation to move into my neighborhood.

But not everyone who works downtown or in the East Bay near a BART station makes a nice tech salary. These buses are aimed only at one class of people – mostly single, mostly high-paid – and they are prime sources of displacement in the city right now. Public transit, that serves everyone, has a different kind of impact, and is less a cause of the housing crisis we’re seeing in places like the Mission.

Wiener brought up Caltrain; electrifying that line and speeding up the trains would make it easier to commute from SF to the Peninsula, and might impact prices near the Caltrain stations. But again: Students use those trains. People who work in modest-paying jobs use those trains. And lots of people take Muni to the downtown Caltrain station from all over the city.

Has tech-bus-driven displacement forced lower-income people who work in the city to move way out of town, far from transit lines, and thus put more people in cars?

The shuttles are supposed to be taking cars off the streets – but are they, overall, given displacement?

It will take a while to study that – and the program can’t exist until the study is done. That means in effect if the supes uphold the appeal, the Google buses will no longer have the legal right to use Muni stops, which would severely limit the number of buses in the neighborhoods. (Oh, unless the MTA decided to take away lots of residential and commercial parking spaces and turn them into bus white zones – and you think people in the Mission and Noe are going to go for that?)

So the supes have the ability to, in effect, shut the program down. The tech companies know that, which is why they’ve been in meetings with several supervisors to look at a compromise.

We don’t know exactly what that would look like at this point, but we know that among the issues on the table are limiting the total number of buses (reducing the current number), charging more for each stop (the city can’t legally force the shuttles to pay more than the cost of administering the program, but the tech companies can volunteer to pay more), and possibly limiting some of the shuttles to hubs, perhaps downtown.

Sup. Jane Kim likes the hub idea, which among other things would make the tech workers ride (and support) Muni, just like the rest of us.

The supes can’t pass regulations mandating these things – but they can do a lot more than pass a toothless resolution. They can force everyone – the MTA, the tech companies, and the shuttle workers – to agree to a way better deal that what we have now. And if that doesn’t happen, they can uphold the appeal and kill the entire program.

So this isn’t at all meaningless. There are, I suspect, at least six votes to uphold the appeal if the tech companies don’t cut a deal. (And if the deal isn’t good for workers and the environment, the appellants won’t withdraw the appeal, and might take the case to court if the supes reject it).

Which is why we might actually see some movement from the tech industry, and we might wind up with a much better deal and much better program – something Mayor Lee could have pushed for in the first place.

You can (and some will) call this an abuse of the California Environmental Quality Act, but the truth is, CEQA has been used for decades to win concessions from developers. City councils and mayors and boards of supervisors that are friendly to well-heeled developers and project sponsors routinely approve bad deals that damage the environment. CEQA gives the rest of us a tool to force better projects.

So that’s what’s going on here. And we will see it play out in the next week or two.