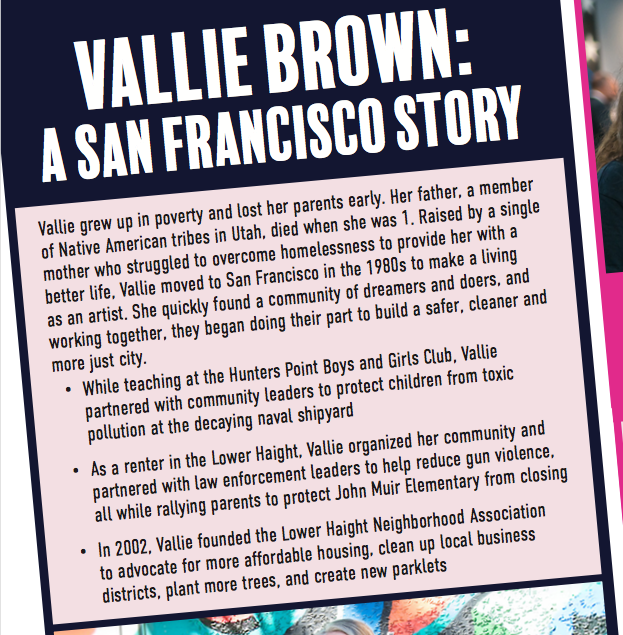

Sup. Vallie Brown has a narrative driving her campaign: She had a difficult childhood, faced evictions and homelessness, and is now working to protect the rights of tenants. Here’s what a Brown mailer says:

Vallie grew up in poverty and lost her parents early. Her father, a member of Native American tribes in Utah, died when she was 1. Raised by a single mother who struggled to overcome homelessness to provide her with a better life, Vallie moved to San Francisco in the 1980s to make a living as an artist. She quickly found a community of dreamers and doers, and working together, they began doing their part to build a safer, cleaner and more just city.

While teaching at the Hunters Point Boys and Girls Club, Vallie partnered with community leaders to protect children from toxic pollution at the decaying naval shipyard

As a renter in the Lower Haight, Vallie organized her community and partnered with law enforcement leaders to help reduce gun violence, all while rallying parents to protect John Muir Elementary from closing.

There’s nothing inaccurate about that, and I respect the challenges she has faced in life and her efforts to overcome them.

But there’s a missing piece that the campaign doesn’t talk about – ever. The SF Weekly broke the story today that Brown was not just a tenant in the lower Haight – she was a landlord who evicted two long-term African American tenants when she moved into their unit.

Nothing she did was illegal. But the fact remains that she was not only a victim of evictions – she was an evictor who forced very low-income tenants out of their home. For a lot of tenant activists, that’s not, and never will be, acceptable.

And her explanation for what happened is pretty weird.

San Francisco has seen over the past few decades a rash of what are called TIC evictions. The early pattern was pretty typical: Four investors buy a four-unit building (or six and six, whatever) for cheap, because the tenants have been there a long time and thanks to rent control, are paying below-market rent. The building isn’t as valuable as income property if the rents are low.

But instead of keeping the property as rentals, the investors evict all the tenants and move in as “tenants in common” – getting around the city’s condo-conversion limits by a legal trick that allows each one to own a unit.

More recently, speculators have gotten into the game, buying up property, using the Ellis Act to evict the tenants, then flipping the units as TICs for a big profit.

According to public records collected by the SF Tenants Union (and I have confirmed it all), Brown and three friends bought the property at 148-152 Fillmore for $275,000 on April 13, 1994. Within days, the group filed eviction notices against all of the tenants (three filed wrongful eviction notices at the Rent Board on April 25.) The unit Brown wound up occupying had tenants named Thomas and Eleanor Cotton; they got an eviction notice April 21.

Ultimately, all the tenants were forced out, and the four buyers occupied the place, which had all sorts of maintenance issues. Over time, Brown fixed it up, and by the time she sold it in 2004, she had bought out the rest of the owners. It sold for $2.6 million.

Thomas Cotton, an African American, was 56 at the time of the eviction, and had lived in the place since 1980. His rent was $205 a month. (That’s not far from what market rent was in the area at the time; I moved into a place six blocks away on Fillmore St. in 1984, and my rent was $265. Fourteen years later, of course, it was way below market.)

Cotton was beyond low-income – he was, in the determination of the Superior Court, indigent: He got his legal fees waived when he tried to represent himself in the eviction case. The court doesn’t waive fees unless you are very low-income.

Brown says she was pretty broke at the time, too, but she clearly could afford a lawyer to do the eviction, and Cotton couldn’t. He finally settled by agreeing to move out if Brown would waive three months back rent that he owed. (Prop. F, the law that guarantees tenants facing eviction the right to a lawyer, might have saved his home if it were in effect back then.)

Brown’s challenger, Dean Preston (who wrote Prop. F), said that “I’m shocked that a candidate with a record of evicting tenants would ever be appointed by Mayor Breed to this seat, or that she would even consider running for District Five supervisor.”

No matter how you spin it, Brown bought a building that was occupied by tenants. She was part of throwing those tenants out, through the legal process of eviction. There is no evidence that she paid them any relocation fees or helped them find other housing.

I suspect Brown might have been able to limit the damage if she just said that she did nothing illegal, that she needed a place to live, that TICs were a popular way for middle-class people to buy homes, and the eviction was unfortunate but she as an owner had the right to occupy her property.

I think it’s a scandal that TICs have been used as a way to evict long-term tenants; it’s a rotten loophole in state law, and should be illegal. Still, she could claim she did nothing that others haven’t done.

Instead, she’s presented a convoluted story.

From the SF Weekly:

Brown says they needed more income from the tenants to pay for building renovations to address problems like mold, and that she tried to work with the tenants so that they could stay. When they couldn’t settle on a rent amount, she and her co-owners moved to evict them.

Two former tenants reached by SF Weekly said they didn’t remember efforts to help them. All three tenants lost their wrongful eviction case and by the fall of that year, they all vacated the building.

But Brown thinks the ultimate problem was the lack of assistance from the city or nonprofits to help make the house livable for a cooperative, while keeping rent affordable for previous tenants. The house simply had too many repairs and they sought capital — or at least, consistent rent payments — to make those improvements, she says.

Jennifer Fieber, a director at the Tenants Union, said some of that is bizarre: “It’s the city’s fault that she couldn’t pay to fix her building?”

On Facebook, Brown says the following:

In 1994, I along with 3 friends, all in our late 20s and early 30s, bought a building in Lower Haight to live communally after being pushed out and evicted from warehouses in SOMA. We saved every last penny we had — I borrowed money for my $4,000 share of our down payment — and we were finally able to buy a building through probate court, without even seeing it first. What we found were four apartments in total disrepair; mold in the walls, holes in the floors, no heat and a leaking roof. We asked the remaining tenants to stay, but understandably given the state of the place, they had not been paying rent for years and did not want to start. I understood that becoming part of a housing collective when you don’t know each other is a difficult move to make. I also got it that they felt the building was in too bad of shape to hang on and pay rent. An Owner Move-In (OMI) eviction was the only way we could preserve their credit.

Let’s parse this for a second.

Brown and her friends bought a building that they had never seen at a probate auction for $275,000. They put up $16,000 cash and got a mortgage for the rest. They found out after they had bought it that it was a total dump and the tenants weren’t even paying rent.

She says they really wanted the existing tenants to stay, but they would have to pay rent, and they didn’t want to. So they had to go.

And in the settlement, Brown agreed to waive three months of Cotton’s back rent — which suggests that he was in fact paying rent.

Here’s the curious part:

No bank is going to give people a mortgage to buy a building with tenants in it as income property unless there’s proof that the tenants are paying enough rent to cover the monthly nut. On the other hand, if the four told the bank they were going to move in, it might be a different situation.

I couldn’t get Brown on the phone, but I got one of her campaign staffers, Leo Wallach, and he confirmed to me that “this wasn’t purchased as income property.”

He told me that the four planned at first to move into one unit, together, and slowly fix up the rest. “They qualified for the mortgage before the auction,” he said.

Brown had to do an owner-move-in eviction to get access to the property, Wallach said.

He said that when she bought out the other owners, she had to borrow against the equity in the place (which is consistent with public records) and that despite the high price tag, she walked away with “about $600,000.”

Among a lot of voters, including some in D5, a message that says a candidate started with nothing but through hard work, managed to buy property and become successful would be perfectly acceptable. (Preston, in his campaign literature, makes clear that his immigrant parents started with little but build a successful business and that he’s a homeowner.)

So why has this entire chapter of more than 20 years in Brown’s history completely vanished from her political resume?

Maybe because the idea that she evicted her tenants, and was part of a group that evicted all of the tenants in a four-unit building at a time when gentrification was transforming the lower Haight, doesn’t fit with her campaign narrative.

I understand her challenges, but in 1994 she bought a building that had tenants in it. And when you buy a building with tenants, you become a landlord — and you take on a lot of responsibilities. She voluntarily put herself in a place where she became a landlord who threw out low-income African American tenants.

That was a choice she made. Now, it’s part of the politics of this race.

“We believe the mayor knew about this when she appointed Brown,” Fieber told me.

If she did, the Mayor’s Office figured the story was old and would never come out. But in politics, the cover up is often worse than the crime.