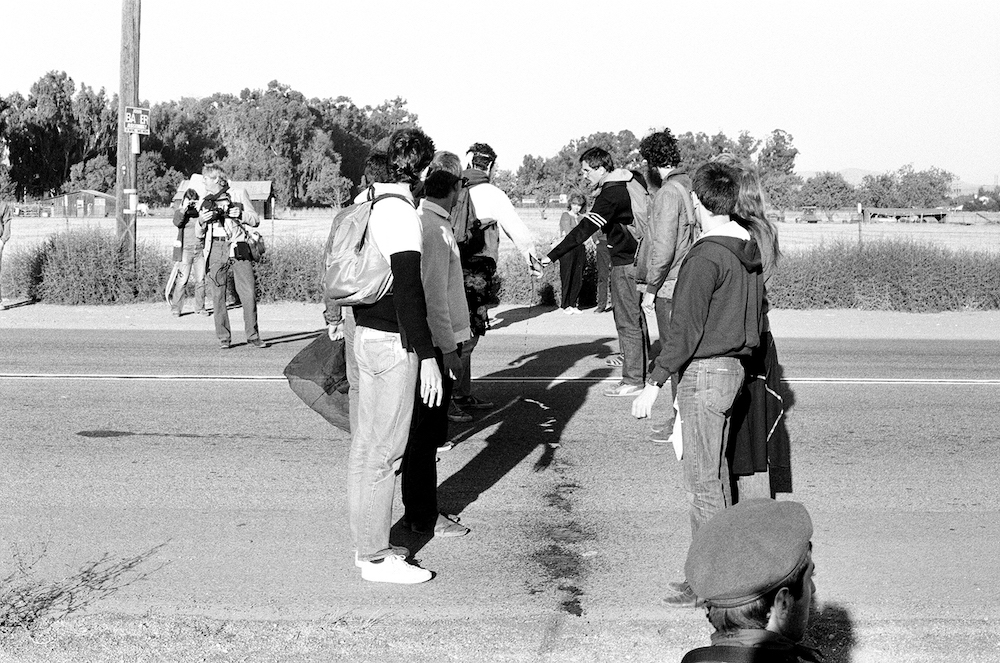

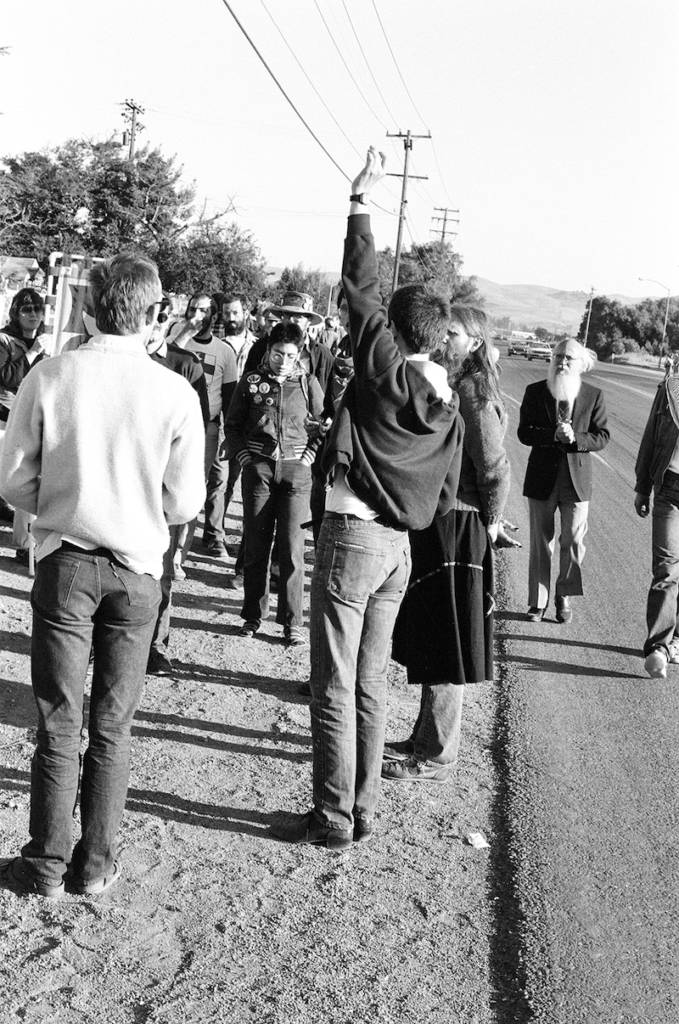

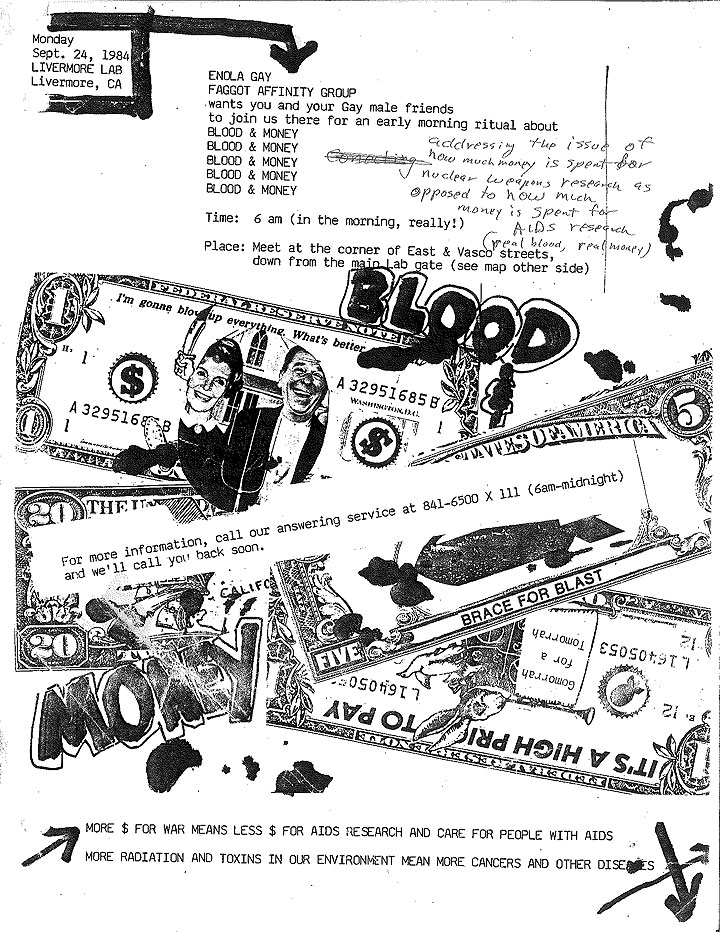

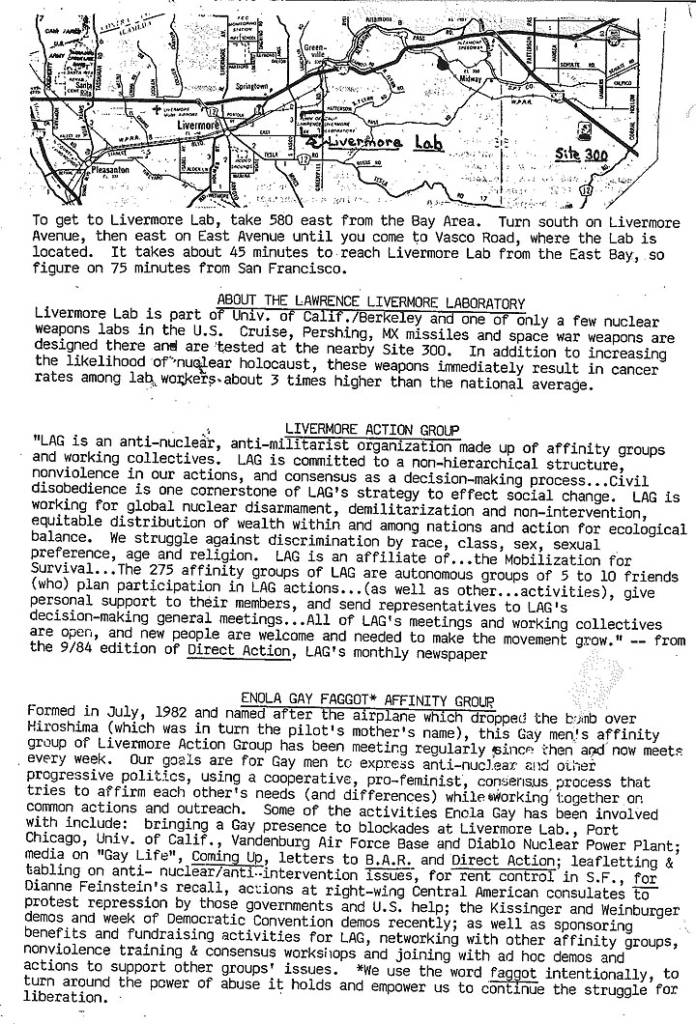

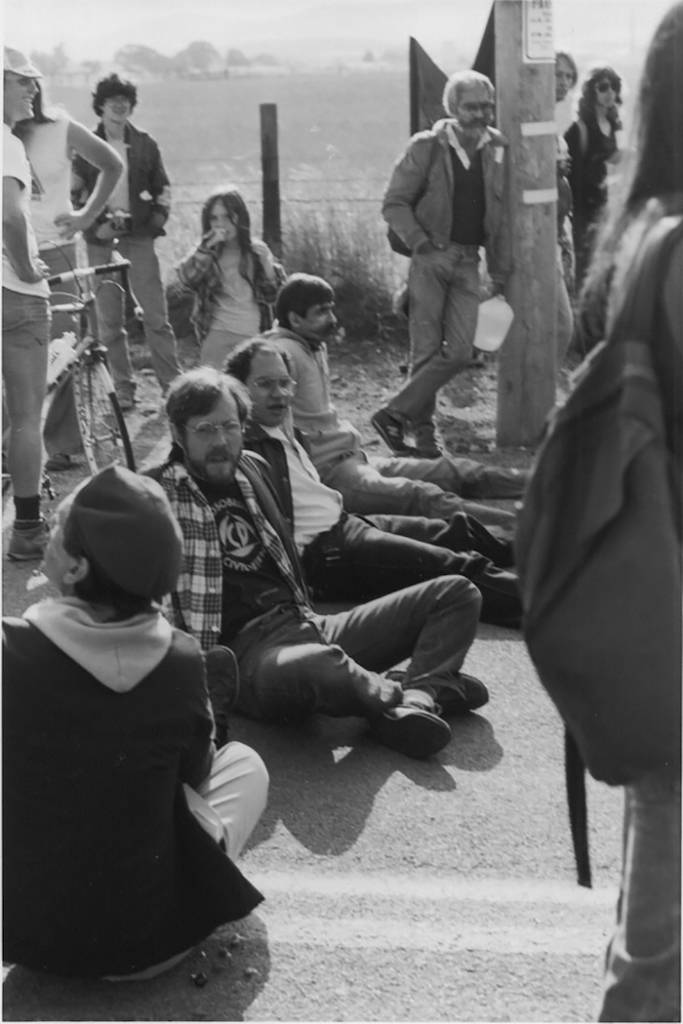

Just around the crack of dawn on September 23, 1984, a handful of gay men gathered outside the gates of the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, a major center for the research and development of nuclear weapons. The men were part of the perfectly named Enola Gay “Faggot Affinity Group”—christened after the airplane that dropped an atomic bomb on Hiroshima, and part of Livermore Action Group, the sprawling anti-nuclear protest network which had brought hundreds of people out to Livermore for a massive civil disobedience action.

“We were moving very slowly. It was around 6am, after all, and I’m sure some of us had been out the night before,” recalled Enola Gay member Jack Davis over the phone. (Davis will be part of a panel Fri/20 at the GLBT Historical Society Museum’s “Enola Gay: The Birth of Militant Gay Activism.”)

As the larger protest moved to block the entrance to Livermore Lab—an action that resulted in mass arrests—Enola Gay members remained briefly in the road leading to the Labs. First, they formed a circle. Then they broke into two rows facing each other and pulled vials of blood from their coats. Slowly, they poured the blood across the road between them, chanting:

blood is holy

blood is sacred

workers that come this way

will cross the blood of gay men every day

Afterwards, moving to the side of the road, the men pricked their fingers and smeared blood on dollar bills, some of them defaced with Enola Gay’s brilliantly camp slogan, “Gomorrah for tomorrah.” Participants were asked to give a personal statement on the action, what Davis called “a litany of needs,” many of which revolved around the theme that gay activists within the Livermore Action Group had adopted: “Money for AIDS, not war.”

“A group of people, including police, watched us form a distance and then moved closer, probably wondering what in the heck we were doing,” Davis said. “It was a quiet and respectful protest. We wanted the people at the Lab to make the connection between their work and our lives.”

This was the “Blood & Money” ritual, which scholar Emily K. Hobson describes as “the first recorded instance of civil disobedience to confront AIDS” in her book Lavender and Red: Liberation and Solidarity in the Gay and Lesbian Left (UC Press, 2016). When asked why the ritual took on such a witchy cast, Davis—a spry-voiced 69-year-old full of sharp little jokes—said, matter-of-factly, “Well, I’m a witch. One of the other affinity group members was a witch, and others were definitely witchy. This was our ritual. We were reclaiming the tradition of witches in the Bay Area.

“I don’t remember if any one member came up with the original idea for the ritual, it just kind of bubbled up from where we were at, at that time, in wanting to make a statement,” Davis said. “But in the end, the other members said, Jack, you lead it.” The recitation of a litany of needs was directly influenced by Bobbi Campbell, the famous AIDS Poster Boy, who had made a similar speech outside the 1984 Democratic National Convention, held in San Francisco. (Campbell died of AIDS one month later.)

“The blood we poured out was mine,” Davis told me. “It was reported that it was fake blood, but it was real—the nurse who drew it had shown me how to dilute it before freezing it to make it seem like more. There were supposed to be three of us having our blood drawn, but there was a music festival in Berkeley that day, and the other two guys never showed.”

“You have to understand that back then, this was really a statement,” Davis said. “No one knew how people were getting infected. Some of my friends had stopped going out dancing because you might get it from other peoples’ sweat flying around. There were stories about bus drivers refusing to touch transfers from people who looked sick, because they might have held the transfer in their mouth. There was no HIV test. No one knew they had it until they started getting lesions. Gay blood was considered dangerous. And here we were, pouring it out on the road. But it wasn’t meant to be a threat. That never even crossed our minds. It was more about saying, ‘We are here.'”

“Another thing was the nature of protest at the time,” Davis said. “In the early ’80s we all worked together on overlapping social justice issues like denuclearization, solidarity with Central America, feminism, racism, police brutality. We didn’t have the word ‘intersectionality,’ and maybe that’s not quite the right word for it. But we were intertwined in a way that rarely focused on one single issue in one single way. It was common for people to have a lot of commitments, to go from one protest to the next. Everyone had to look at their calendars,” Davis said.

“Enola Gay would set up a table in the Castro at Hibernia Beach, and I just remember if you went from left to right you would see pamphlets and flyers from a dozen different causes. When we worked with CISPES, the Committee in Solidarity with the People in El Salvador, we had a chant:

gay, black, straight White

same struggle same fight

money for AIDS not for war

US out of El Salvador

Enola Gay was just one queer affinity group within the Livermore Action Group—others included Body Electric, Oz, and Queers United in Efforts to End Repressive Society, or QUEER. And in 1983, after the US invaded Grenada, Enola Gay participated in a mock invasion and “liberation” of Angel Island, with Davis leaping off a boat to claim it in the name of the Faggot Liberation Army. “When we heard there was going to be a mock invasion, we in Enola Gay said, ‘Fuck that—we don’t want to be soldiers, we want to be cheerleaders.’ So that’s how we dressed.”

In 1984, three years before ACT-UP was launched in New York City, AIDS activism was just getting started. Enola Gay’s “Blood & Money” ritual preceded by a year John Lorenzini chaining himself to the San Francisco office of the US Department of Health and Human Services, wearing an “I am a person with AIDS” t-shirt, under a banner reading “People with AIDS Chained to a Sick Society.” (According to Hobson, this was the second recorded instance of civil disobedience to confront AIDS.)

The “Blood & Money” ritual was short, but Davis tipped off a friend at the Gay Community News, a paper that ran nationwide. (You can read the article and Davis’ recollections on the awesome FoundSF site.) “We quickly moved out of the road after the ritual for a very good reason—we didn’t want to get arrested,” Davis said. The previous year, at a similar Livermore Action Group protest, more than a thousand people were arrested, fined, and held in circus tents in a civil rights debacle that Davis described as “extremely unpleasant.”

“They held people over Gay Pride weekend, so of course we had a Pride parade—and the police did not like that at all,” Davis said. Renowned poet Robert Gluck, another Enola Gay member who took part in the ritual and will be speaking on the panel, described the post-Pride circus tent prison scene in his book Communal Nude (Semiotexte 2016):

“The captain bellows: ‘This is not Camp Friendly or Camp Sunshine!’ New rules: single-file lines; no wearing sheets; no wearing tampons (the women had a parade too); only ‘discreet homosexual activities’—in a tent of 400? We speculate they mean the men’s-movement men; they are mostly straight, but touch each other intensely.”

“None of us wanted to go through that again,” Davis said.

Enola Gay disbanded in 1986, and many of its members found their way into ACT-UP. Davis, now retired, still lives in San Francisco, practicing art and being a witch. “Writing a ritual that was civil disobedience was not a new thing. As a visual artist among other visual artists—we were familiar with that form of protest. What we said to ourselves at the time was, ‘All we know is that you can get HIV from body fluids, which means we have to be afraid of them. But there’s a way to treat them that isn’t just about fear.'”

ENOLA GAY: THE BIRTH OF MILITANT GAY ACTIVISM

Fri/20, 7pm, $5

GLBT Historical Society Museum, SF.

More info here.