Freakonomics Radio is usually pretty interesting (although sometimes they get it really, really wrong. In one episode a guest argued that the reason urban housing prices are so high is that landlords are required to keep their property up to code).

The episode I heard on the radio this weekend was excellent – and has a message for policy makers at every level in this country. The question was one that’s come up quite a few times in the past:

Why are people in the Nordic countries, in this case Denmark, so much happier – by almost any standard – than people in other places?

The simple answer: They have far less economic inequality. Taxes on high incomes are high. Displays of wealth are frowned upon. There’s a well-funded, effective social safety net at every level. People are just less stressed.

A woman who was born in Britain and recently moved to Denmark told a remarkable story: She’s a business professional, and she talked about the person making her coffee at a café, and said that the could talk as equals – “because after taxes, we’re taking home about the same amount.”

She’s good with that. So, apparently, are most people in the country. The message: If you let a few collect too much wealth, it makes almost everyone unhappy. If you tax wealth at a level that makes most people relatively equal, almost everyone is happier. It turns out that taxing the rich isn’t just good for the revenue of a nation and thus the safety net; it’s good just by itself because it decreased inequality – and increases happiness.

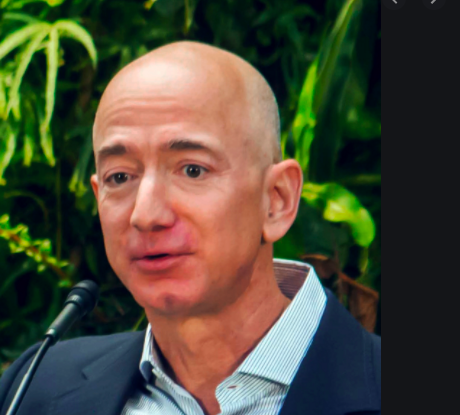

In other words, if we had taxed the multibillionaires like Bill Gates and Jeff Bezos to the point where they only had, say, $5 billion instead of more than $100 billion, not only would we have enough money for single-payer health care and great public schools, but we’d all be happier people.

Meanwhile, I’m reading one of the most important books on the US economy to come along in a while. It’s called The Sum of Us, by Heather McGhee, and it starts with the question, “why can’t we have nice things?” We, of course being the United States, and “nice things” being good public schools, a functioning public health-care system, adequate wages that keep people out of poverty, affordable housing … the things that ought to be a part of any modern society.

One major reason, she argues, is that the great social achievements of the New Deal and the post-War era were mostly designed to make life better for white people – and after the Civil Rights Movement forced the nation to start, slowly, allowing Black people to benefit, too, the whites in power rebelled.

She uses the metaphor of the towns in the South that decided in the 1950s that they would never integrate public pools – so they drained the pools and shut them down. Now neither white people nor Black people can swim.

It’s exactly what happened when Ronald Reagan campaigned on the slogan that “government is not the solution, government is the problem” and talked, in hardly even coded language, about “welfare queens.” The message: Government takes tax money from white people and gives it to Black people. So we need to cut taxes and shrink government.

Of course, McGhee argues, that hurt a lot of white people, too. She talks about the “zero-sum paradigm” that people in power have been peddling — the idea that racial groups are competing for economic gains. That, she says, is “a lie …the wealthy and the powerful are selling the zero-sum story for their own profit, hoping to keep people with much in common from making common cause with each other.”

Her subtitle is “What racism costs everyone and how we can prosper together.”

I wonder, of course, what would happen in Denmark if a new and large immigrant population that didn’t look like the Danes started getting the same advantages as the mostly white current population does.

But between Denmark’s taxes on the rich and McGhee’s point that while progressives talk a lot about social class, much of our economy has been shaped by racism that hurts (almost) everyone, there are huge some prescriptions for policy here.

Six supervisors are pushing emergency legislation to keep 2,200 hotel rooms open for the duration of the pandemic – setting up a clash with the Mayor’s Office, which is trying to reduce the number of people in the rooms.

That measure comes up at the Budget and Finance Committee Wednesday/24, where it’s likely to pass – but it needs eight votes at the full board.

The bigger question is why the city isn’t using the money it has from the feds and Prop. C to buy these hotels right now. Perhaps that will come up at committee. The meeting starts at 10:30am.

A fairly large number of the serious building permit violations in San Francisco are connected to a fairly small number of operators who are known as “serial permit scofflaws.” The Land use and Transportation Committee will consider legislation Monday/22 that would create a database of these scofflaws that the Department of Building Inspection can track, and would add compliance control to projects involving those individuals.

The bill, by Sups. Hillary Ronen Aaron Peskin, and Matt Haney, is in response to a long list of problems at DBI.

The committee will also hold a hearing on the success of the Safe Parking and Vehicular Triage Center (a fancy term for a place where people can live in their vehicles without hassle) at Balboa Park. By almost all accounts, the temporary program has worked well and ought to be expanded to other districts.

A news report out of Lousiana and Texas states that the company running a private prison in the Tenderloin is failing to provide adequate heat for ICE detainees.

At the South Texas Family Residential Center in Dilley, Texas, advocates say parents and children have been living with overflowing toilets, thirst, poor hygiene, and heat that fades in and out. Twenty miles away, at the South Texas ICE Processing Center in Pearsall, advocates say detainees who complained about the cold faced retaliation. At the Pine Prairie ICE Processing Center in Louisiana, a detainee interviewed by The Intercept reports that the segregation unit, akin to solitary confinement, has no heat.

The Geo Group still has contracts with both the state and the feds for its 111 Taylor Center in San Francisco, where there have been multiple COVID outbreaks.