Here’s the headline of the year, although the Chron keeps dishing up wonders: A socialist supports socialism.

It’s hardly unusual to hear Sup. Dean Preston, a proud Democratic Socialist, saying that capitalism is a root cause of homelessness, drug addiction, and crime. That’s something that many economists, sociologists, criminologists, and even the Pope have said repeatedly.

But the way the Chron framed this—as some kind of weird idea, “prompting critics to question the logic of the supervisor, who’s the only Democratic Socialist on the board,” raises an important question in politics and news media.

Have we not gotten beyond the point, especially in San Francisco, where “socialism” is some sort of radical, frightening concept and criticizing capitalism is some kind of taboo?

At this point, polls show that US Democrats, especially people under 30, have a more positive view of socialism than capitalism. As many as 70 percent of young voters think the very rich got their wealth by cheating the system, and taxes on wealth are increasingly popular.

There’s a reason Sen. Bernie Sanders came pretty close to winning the Democratic nomination for president, and is currently more popular among Democrats than President Joe Biden.

The Chron story is based on comments Preston made to a right-wing film crew from England that was making what the paper called an “investigative documentary” on San Francisco’s problems.

Actually, it’s a piece of conservative propaganda, but never mind. Preston told me his comments were taken out of context, and this was never supposed to be a documentary about capitalism, but he stands by the statement that capitalism, at least our current neoliberal version, is one of the major causes of our social problems.

And why wouldn’t he? Why would this be “prompting critics” (who are not cited in the story, except for a billionaire-funded “Dump Dean” website) to question his priorities, which are and have always been affordable housing and tenant protections, among other things?

It’s as if the Chron is stuck in the 1950s, with a “red scare” mentality that fundamentally misses the point of what Democratic Socialism is about today.

First: Even most socialists agree that there’s no clear or easy definition of what that term means in today’s United States. Socialist political agendas run a pretty wide spectrum, from those who think that the public sector should take over most essential services, including housing and utilities, to those who are good with market systems that are properly regulated.

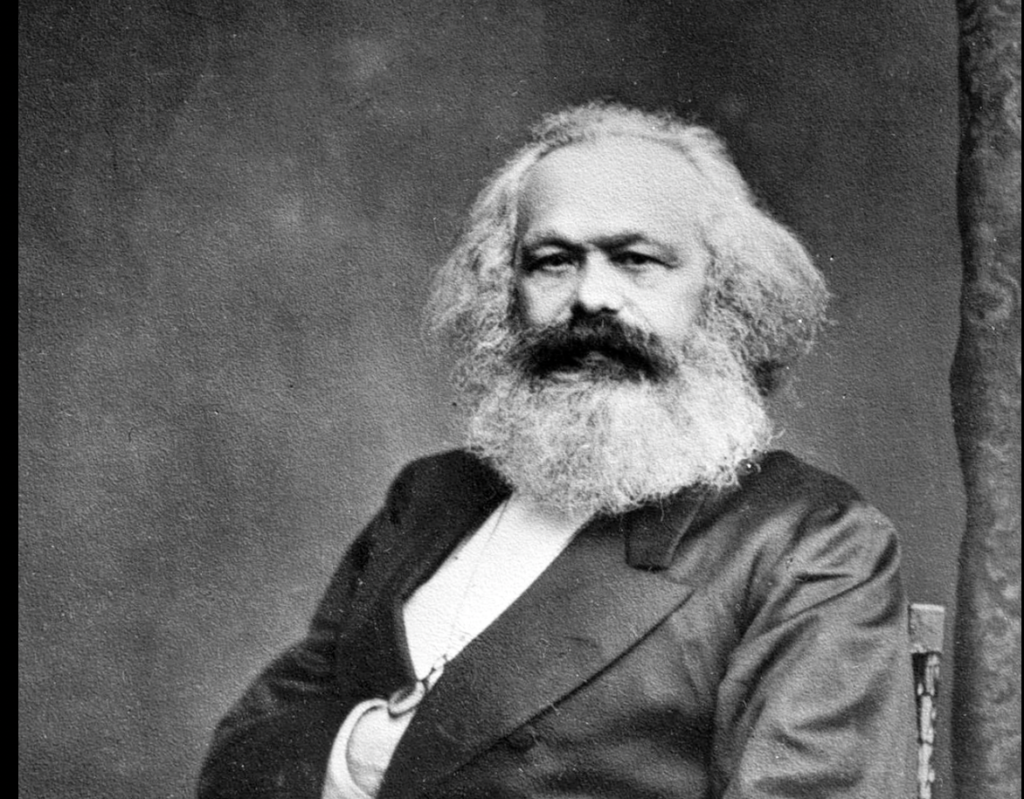

There are Marxists in the US who argue that the state should seize most of the means of production, but there are also a lot of folks who call themselves socialists who think a version of capitalism that features much higher taxes on the rich, strong trade unions, and a much more robust safety net would be a huge improvement.

All of us agree that modern neoliberalism is an utter failure.

I keep coming back to this: If the level of economic inequality in the US today was the same as in 1975, the bottom 90 percent would have an additional $50 trillion.

That’s a staggering number. It’s enough to end homelessness in the country, provide free health care and education to all, make a huge dent in the desperation that leads to crime and opioid addiction … and the top ten percent would still be doing just fine.

The US economy between 1946 and 1980 wasn’t “socialist,” by the common meaning, but rich people paid as much as 80 percent of their marginal income in taxes. That meant, among other things, that as the late Tom Hayden once told me, “nothing used to cost much.” Hardly anyone could afford to spend $100,000 on a house, so houses cost $10,000. That’s not about the Yimbys and supply-side economics, it’s about what the housing market is always about, which is demand.

When I arrived in San Francisco in 1981, there were almost no homeless people. At the Haight Ashbury Switchboard, where I volunteered, you would also find some guy (always a guy, the women were smarter) who thought it was still the Summer of Love and some “digger” was going to offer a “crash pad,” but they quickly got the message.

An indigent adult could get $350 a month plus food stamps from the General Assistance Office. You could rent an SRO hotel room for $25 a week. Rooms in a shared flat went for $125 a month.

The federal government paid for cities to build public housing.

There wasn’t anywhere near today’s level of economic inequality. Stanford MBA’s used to brag about making “twice our age,” which means like $50,000 a year. People who made a lot more than that paid high marginal taxes, and stock options, which hardly existed, were taxed at a reasonable level as capital gains.

Then came Reagan, and the tax cuts for the rich and the devastation of the safety net, followed by Bush, and Clinton, and Bush, and Obama, and Trump, and Biden—and none of them, Democrat or Republican, has undone the tax cuts that allowed the massive fortunes we see today.

There were drug addicts in 1981; the city was dealing with a heroin and crack epidemic (and by the way, the number of homicides was about ten times what it is today).

But we didn’t see tent encampments on the streets, and the Tenderloin was a low-income neighborhood that looked nothing like it does today.

Anyone who seriously thinks that homelessness and despair are not in part a result of neoliberal capitalism is delusional.

We can argue about solutions to local problems, and we have to accept that some of our crises require changes at the state and federal level. But Preston’s comments aren’t radical, or even newsworthy; they’re just reality.