Are the wheels starting to come off the Yimby bandwagon?

The question may seem absurd. Last December, Yimbys took over the Bay Chapter of the Sierra Club, which for the first time endorsed CEQA-hating Scott Wiener. In late February, Yimbys closed out their 2024 annual conference, an event that attracted 600 “red” and “blue” attendees and garnered coverage hailing the movement’s growing bipartisan support.

The Biden administration’s 2024 Economic Report of the President, released on March 24, claims that “zoning reform” will increase the supply of affordable housing and cites as a model, among other examples, California’s RHNA process. Meanwhile, the Yimby mystique continues to enthrall the California Legislature, as indicated by the Terner Center’s survey of current “pro-housing” bills, whose targets include development impact fees and environmental protections for the California coast.

Yimbyism rules. But it’s taking some hard hits from unexpected sources.

Housing Action Coalition calls for higher rents

In January, Corey Smith, the executive director of the Housing Action Coalition, told the San Francisco Planning Commission that if new housing is going to get built, “we need the rent to go back up. I know that’s counter-intuitive and insane to say out loud but it’s the truth.”

Tim Redmond commented: “Correct. If rents and housing prices go up, more developers will see more profit, and will be more likely to build more. But that’s the opposite of what the Yimbys have always said.”

Arizona Governor Katie Hobbs (Dem) vetoes a major Yimby bill

On March 18, Arizona Governor Katie Hobbs, a Democrat, vetoed House Bill 2570, the Arizona Starter Homes Act. Writing in the Arizona Republic, Stacey Barchenger reported that HB 2570 “would have prevented Arizona municipalities from requiring homeowners associations, minimum home sizes and certain building setbacks, among many other provisions. The bill effectively allowed the state a greater say in a process that is typically reserved for local jurisdictions.”

The bill’s supporters, mostly Republicans in the Legislature plus “a handful of Democrats” and “social justice advocacy groups,” “argued [that] local zoning regulations set by municipalities have infringed on private property rights and fueled the current housing shortage. By cutting red tape, building would be easier and increase the housing supply.”

According to Hobbs’ office, the Department of Defense and the Professional Fire Fighters Association of Arizona asked her to veto the bill. “These groups,” wrote Barchenger, “cited concerns about development in noisy or ‘accident potential zones’ near Arizona’s military installations, and difficulty in responding to emergencies if density is increased, respectively.”

Other opponents included the Neighborhood Coalition of Greater Phoenix, whose members included the mayors and vice mayors of Phoenix, Mesa, Goodyear, and Yuma. They said that the bill “would do little to require affordable housing, a crisis [the measure] purports to address.”

Hobbs waited until the last day allowed in the Arizona Constitution to act on the controversial bill. Explaining her veto, the governor said “’the measure would put Arizona ‘at the center of a housing reform experiment with unclear outcomes.’”

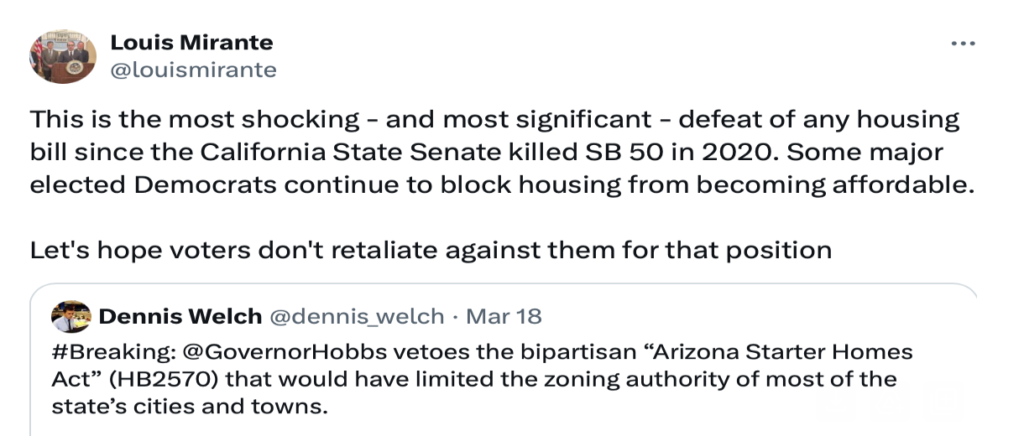

Bay Council Vice President of Public Policy and former California Yimby Legislative Director Louis Mirante tweeted:

The New Republic publishes an attack on Yimbyism

On February 17, The New Republicpublished Michael Friedrich’s “The Case Against Yimbyism.” Friedrich homes in on “the policy that unites Yimbys,” upzoning—permitting increased heights and densities. Referencing Cameron Murray’s deconstruction of “the Auckland myth,” Kevin Erdmann’s debunking of “the Minneapolis miracle,” and a 2023 study from the Urban Institute, Friedrich argues that “the evidence is weak” that upzoning will lower housing costs and generate housing production. Moreover, “[Yimbys] are…explicit that deregulation won’t help those at the bottom of the market.”

Friedrich doesn’t dismiss the Yimby position on “exclusionary” zoning. Indeed, such rules, he writes, “are rooted in harmful racist policy,” and “abolishing them is justified.” He also cites studies that “show that new development slows rent growth both in neighborhoods and citywide.” Plus, “it’s relatively well documented that when developers build new high-end apartments, it eventually frees up more low-cost apartments, in a process that housing scholars call ‘filtering.’” (He doesn’t observe that the reasoning behind these claims is disputed.)

For Friedrich, the problem is that while “[t]weaking the insane minutiae of local permitting law and design requirements might bring marginal relief to middle-earners, it provides little assistance to the truly disadvantaged.” Instead, “the cause of lasting housing justice” requires “provid[ing] homes as a public good”: instituting rent control and varied methods of capping rents; passing just-cause eviction laws; and repealing the Faircloth Amendment, the federal law that drastically limits the amount of new, federally funded public housing stock. “From there, the federal government should reinvest public funds in building homes to rent affordably,” taking Vienna’s affordable housing system as a model.

What’s distinctive about Friedrich’s piece is not its critique of Yimbyism. Others, some of whom he cites, have raised the same objections. It’s that, when nearly the entire media, from Mother Jones to the Wall Street Journal, is touting the Yimby line, such objections have appeared in a respected liberal publication with a national readership.

CA Yimby Policy Director’s bungled response to Friedrich

On February 18, the day after Friedrich’s article appeared, California Yimby Policy Director Ned Resnikoff posted a Substack piece headlined “The Case Against the Case Against Yimbyism.” There he reports that Friedrich interviewed him twice and provided “ample time to respond to his criticisms of Yimbyism.” Little of their discussion made it into The New Republic article. Feeling “that it was important to correct the record,” Resnikoff decided “to address Friedrich’s argument at length.”

“Social” housing with profitability

Contra Friedrich, Resnikoff maintains that “Yimbys support a mix of [market and non-market policies.” For example, California Yimby “has sponsored social housing legislation,” specifically Alex Lee’s failed 2022 bill AB 2053.

But the real thrust of AB 2053, as Calvin Welch has explained, was to create a state agency, the California Housing Authority, “able to overrule or ignore local housing policy and issue debt for new housing construction.” As stated in the bill, the agency’s “core mission” was “to produce and acquire social housing developments for the purpose of eliminating the gap between housing production and regional housing needs assessment targets and to preserve affordable housing.”

Jumping on the latter goal, Welch emphasizes that this was about preserving, not increasing, California’s affordable housing supply. That figured, given that the RHNA “targets are overwhelmingly market-rate.” Just so, “AB 2053 sees “social housing” as being overwhelmingly “market rate.”

To make the point absolutely clear, Section 64724 (a) [of the bill] states “in all its operation the authority seeks to achieve revenue neutrality over the long term.” The bill defines “revenue neutrality” as “a system in which all monetary expenditures that result from the development and operation of social housing owned by the authority are returned to the authority through rents, payments on leasehold mortgaged, or other subsidies.

And what was supposed to make revenue neutrality work was rent and mortgage cross-subsidization, the true heart of Lee’s social housing concept. The legislation defines cross-subsidization as “a system in which below-cost rents and leasehold mortgages of certain units are balanced by above cost payments in other units within the same multi-unit property so as to ensure the property’s overall revenue meets development and operational costs.”

Welch comments:

How “cross-subsidization” would work in the saving of an existing building when the market purchase price has to be fully repaid is unclear. The legislation allows for some tenants to be removed, so the assumption appears to be that the poorer tenants leave, the better-off stay.

Noting that “closing the gap” on meeting the RHNAs “means new construction,” Welch writes:

How “cross-subsidization” works in new construction is a mystery. Other than an embrace of an ethics rarely found in real estate, what program elements motivate an “above market” housing shopper to pay more for a similar unit in a new building than a low-income resident would pay in the same building? The bill offers high income owners the right to sell their publicly developed units for an amount that includes not only the original price, any capital improvement, inflation AND a “reasonable return on investment.”

His conclusion: “It seems, then, that the primary inducement is the same as it is for any real-estate investment: Profit.”

Rent control, Yimby-style

Resnikoff’s other example of Yimby support for non-market policies is California Yimby’s endorsement of rent stabilization.” He doesn’t reference a specific measure, but presumably he means AB 1482, the 2019 Tenant Protection Act authored by David Chiu.

A page on the California Yimby website entitled “How Should We Think About Rent Control” notes the organization’s endorsement of the bill. Written by Max Dubler, this “primer” appears to equate the measure with rent control. Dubler cautions: “it’s important to design rent regulations to maximize tenant stability while avoiding the negative consequences that can come from bad policy design.”

Unfortunately, AB 1482’s poor design has destabilized the lives of many tenants. The law caps annual rent increases at five percent plus the rise in inflation, with a maximum ten percent increase. The problem is that AB 1482 exempts housing that’s

· Legally restricted to households of very low, low, or moderate income

· Subject to an agreement that provides housing subsidies for persons and families of very low, low, or moderate income

· A dormitory “constructed and maintained in connections with any higher education institution within the state” for use of their students;

· Subject to rent control

· Been “issued a certificate of occupancy within the previous fifteen years” from the current date

The upshot is that the bill does not protect hundreds of thousands of the most vulnerable tenants in California, some of whom have seen their rents increase as much as 25 or 30 percent.

Being a Yimby means never saying sorry

In a seeming concession to Friedrich, Resnikoff urges “efforts to repeal the Faircloth Amendment and build more social housing in the United States.” But his enthusiasm for social housing is qualified. Resnikoff offers no evidence that repealing Faircloth is a position held by Yimbys at large or even California Yimby. And he “remain[s] skeptical that social housing as a model will ever scale up to represent a large share of all U.S. housing—certainly not within anything approaching a reasonable time frame.” Friedrich, he notes, doesn’t “subject the Vienna model to the sort of scrutiny he reserves for the research on private housing development.” More broadly, Resnikoff argues that “Friedrich’s sketchy, speculative strategy” begs questions of practicability: “How long is this”—“convert[ing] the majority of all urban housing to public ownership”—supposed to take, and what are intermediate steps supposed to be?”

For the record, Friedrich never advocates converting all urban housing to public ownership. What he seeks is ensuring that “the truly disadvantaged” have “safe and stable” homes. That said, Resnikoff’s questions about the implementation of an ambitious public housing agenda are valid.

Just as valid, however, are questions about the practicality of Resnikoff’s preferred course of action: follow Yimbyism’s dicta and loosen regulations on the private real estate sector. That program is “already working,” so abandoning it “in favor of Friedrich’s sketchy, speculative strategy would be not just imprudent but actually irresponsible.” Yes, it would—if the Yimby program were demonstrably successful.

If anything, however, Resnikoff advertises Yimbyism’s failings. The exposé unfolds as he reviews the scholarship that Friedrich cites to show that upzoning has failed to spur private homebuilding or lower housing costs. “[Friedrich’s] case,” he asserts, “is based on a selective reading of the relevant literature that leads him to misinterpret some findings while downplaying others.”

Resnikoff immediately undercuts that criticism:

For example, Friedrich correctly notes that there is limited research on the long-term impacts of major Yimby reform. While some of the early indicators from Minneapolis and Auckland have been promising, we simply don’t know for sure whether land use liberalization had put those cities on a path to housing abundance.

Wait a minute. “[W]e simply don’t know for sure whether land use liberalization had put those cities on a path to housing abundance”? Doesn’t that mean that the Yimby agenda is subject to the same objections—it’s “sketchy and “speculative”—that Resnikoff levels at Friedrich’s pitch for publicly funded housing?

If Resnikoff had stopped there, the damage he’d done to his cause would have been bad enough. But he goes on—and on:

Even if the Minneapolis and Auckland reforms “worked”—which is to say, even if no further reform is needed—it will be some years before homebuilding in both cities catches up with demand for housing. And it will probably take even longer before the academic literature catches up to real-world conditions and successfully isolates the impact of land use liberalization in each city.

In other words, if scholarship doesn’t corroborate Yimby assumptions, the problem is that the research is lagging behind reality, because reality reliably incorporates evidence that “land use liberalization” works—that is, lowers costs and generates lots of housing. The possibility that the assumptions are flawed is not on the table. That scholarship hasn’t detected the evidence that corroborates those assumptions

isn’t an argument against YIMBY reform. Instead, it is a reminder that the academy can only do so much to guide policy. We simply don’t have time to wait around for conclusive findings from Auckland and Minneapolis before we tackle the housing crisis in other cities. And if such findings were a precondition for action, then Auckland and Minneapolis would never have done anything in the first place, and we wouldn’t even have the initial results from their experimentation with YIMBY policies.

So Yimbys regard cities as Petri dishes where they can try out their theories? If Resnikoff is to be believed—and as California Yimby’s Policy Director, he deserves such credence—they do.

Compounding the weakness of his argument, Resnikoff continues:

Where the academic research on a particular course of action is incomplete or ambiguous, policymakers need to make use of what evidence is available. And the evidence in favor of land use reform is considerable: while we’re still waiting on verifiable examples of total victory in cities that have implemented Yimby policies, there is plenty of research pointing to a relationship between land use reform and improvements in housing affordability.

More hyperbole here: nobody is asking for evidence of Yimbyism’s “total victory.” But Resnikoff’s standard of success—“a relationship between land use reform and improvements in housing affordability”—is pathetic.

He specifies the nature of that relationship by pointing to a study cited by Friedrich, Xiaodi Li’s 2019 paper on the effects of rents on high-rise apartment construction in New York City. Li found that for every ten percent increase in housing stock “within a 500-foot buffer,” residential rents decreased one percent, and residential property sales prices decreased within 500 feet.

Friedrich had commented on Li’s findings:

For Yimbys like [Sonja] Trauss and Resnikoff, such research presents important proof that, on the margins, building moves rents in the right direction….But as a practical matter, marginal changes don’t add up to affordability for most. Even if developers somehow built 50 percent more housing in New York City, the median one-bedroom unit would still rent for $3,548 per month (if applying the study’s findings to today’s market).

Resnikoff pounces on Friedrich for extrapolating Li’s findings to all of New York City, about which more in a moment. He also criticizes Friedrich for taking “the measured one percent effect size too literally.” As to the latter:

Li’s research, while valuable, did not uncover some hidden law of Newtonian physics, where a ten percent increase in housing stock will always lead to a one percent reduction in rents. The most useful components of her findings—as in all similar research—are the directionality and the significance, not the effect size. The strongest claim we can make based on her work is that there is a statistically significant relationship between homebuilding and rent decreases within a 500 foot radius, and it appears to be causal. That’s pretty good!

Resnikoff has already dismissed scholarship that doesn’t confirm Yimby hypotheses as lagging behind “real-world conditions.” Now he discounts real-world conditions that fall short of those conjectures. What’s “most useful” about Li’s finding is not the “effect size,” which is to say, their practical significance. Rather, it’s their “directionality” and “significance,” specifically their statistical significance. Rents are moving in the right direction, which is to say downward. Just a bit, but that’s enough for Resnikoff.

What’s crucial, however, is that Li found “a statistically significant relationship between homebuilding and rent decreases within a 500-foot radius, and it appears to be causal.” Which is to say, she found that an effect was probable, i.e., mathematically significant, in a specific location under specific conditions. Whether or to what extent that effect is replicable in other locations and under other conditions remains to be proven.

Given that Resnikoff bases his reservations about public housing on its purported impracticability, it’s odd to find him privileging statistical significance and discounting effect sizes—until you realize that he’s operating with a double standard that favors Yimby assumptions and discriminates against their critics.

The same bias warps his position on the replicability of Li’s findings. He properly criticizes Friedrich for extrapolating those findings to all of New York City. But he makes the same mistake when he holds that Li’s findings show that “there is a significantly significant relationship between homebuilding and rent decreases within a 500 foot radius.” As per his own argument, what Li found applied to the specific area under the specific conditions she studied—not rents within a 500-foot radius per se.

Far more damning is Resnikoff’s criticism of Friedrich’s failure to note the limitations of the 2023 Urban Institute study, starting with

the paper’s scope of observation: the authors aim to observe the effect of land use reforms over no fewer than eight metropolitan areas, including the regions around Los Angeles, Chicago, Dallas, Philadelphia, and Miami. These are all very different regions, with wildly histories, demographics, housing markets, regulatory regimes, geographies and built environments.

Land use is simply going to mean very different things in different contexts: a city that already has very permissive zoning might not see much change in housing supply if you upzone further, whereas a city with very strict zoning might see an immediate supply response following even modest tweaks to the zoning code. Similarly, developers might not build much new housing in an area with a collapsing population even if you make it easier for them to do so. Trying to average out the effect of land use reforms over these [eight] jurisdictions can only tell us so much.

Agreed. So why do California Yimby and its allies push blanket upzoning and other one-size-fits-all policies?

I wonder if Resnikoff ran his riposte by his colleagues at California Yimby or dashed it off in a fit of pique, because what he produced reads like the case against “The Case Against the Case Against Yimbyism.”