As the major studios step up cannibalizing their own libraries for remakes, and milking franchises dry—this week’s big commercial release is Deadpool & Wolverine, regarding which our only comment is “No comment”—creative individuality becomes an ever-more precious commodity at the movies. Fortunately, a couple retrospective series, new documentary portraits, and idiosyncratic genre pieces provide an antidote of cinematic iconoclasm onscreen.

Renegades at BAMPFA: Chytilova, Shimizu

The Czech New Wave was one of the chief wonders in a revolutionary decade for the medium, the 1960s—though this particular artistic revolution got pretty well squashed when Russian tanks rolled in to crush the nation’s rebellious, liberalizing “Prague Spring.” Among those who suffered the political-cultural fallout were Vera Chytilova, who’d been among the trailblazers in an extraordinary film epoch. Unlike some colleagues, like Milos Forman and Ivan Passer, she did not flee to the West—and found herself blacklisted at home for the next decade.

It was a deplorable if temporary suffocation of one of the most distinctive, playful voices in cinema worldwide, as demonstrated in BAMPFA’s Something Different: The Films of Vera Chytilova, which runs in Berkeley this Fri/26 through August 30. A determined lone female crasher in a boy’s club, she began making short and mid-length works that straddled narrative and documentary forms, using nonprofessional actors—though her social critiques had little of the pathos-laden sobriety of neorealism.

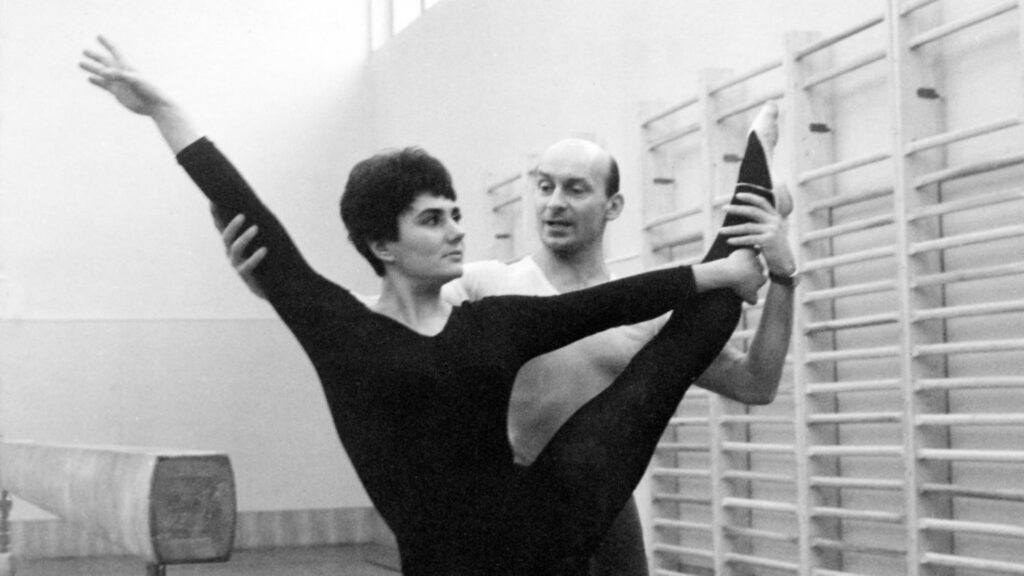

Those early works (including Ceiling and A Bagful of Fleas, both 1962) will be shown on one program August 14. Their approach carried over to her first feature, 1963’s Something Different, which contrasts the differently straitjacketed lives of a competitive gymnast (actual Olympic gold medalist Eva Bosakova) and a neglected housewife (Vera Uzelacova). These slices of life feel real, yet are simultaneously unpredictable, almost anarchic.

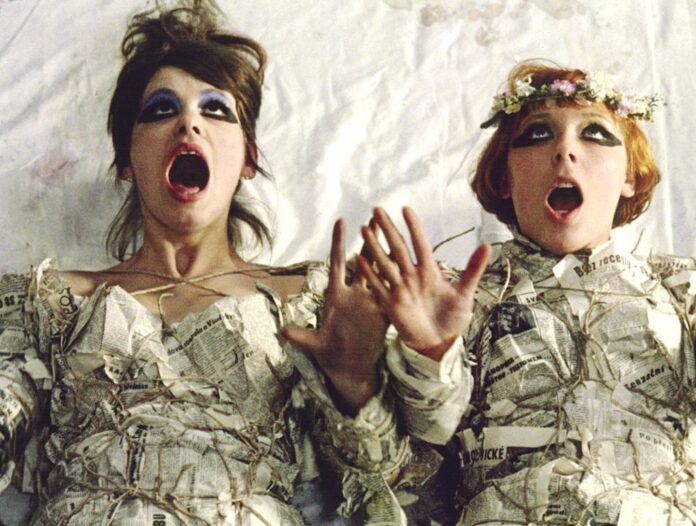

That latter quality exploded in her most famous film, the 1966 Daisies, which both begins and ends the series. While she told them it was a satire of Western consumerism, government watchdogs weren’t at all sure that this marvel of slapstick surrealism—in which two monstrously selfish young women cavort and con their way through a funhouse of visual invention, outraging every propriety—wasn’t in fact a middle finger raised at their own expense.

They were baffled again by 1970’s Fruit of Paradise, a modern spin on Adam and Eve set at a health spa. It was equal parts experimental and farcical, again dazzlingly photographed by the director’s husband Jaroslav Kucera. But this time it was decided that whatever she was saying constituted an offense to the Communist state. So Vera Chytilova did not make another film until 1980’s Panelstory—a pretty riotous ensemble comedy about life in a high-rise Prague housing development, where bureaucracy rules… ineptly. Somehow that got a pass from the censors, and her career resumed with a furious energy for another quarter-century. (She passed away in 2014, at age 85.) There are scattered gems amongst her hard-to-find later titles, but the Pacific Film Archive series goes no later than Panelstory, which found her joyously—if also cynically—unbowed.

Another stubbornly independent character is celebrated in Hiroshi Shimizu: Notes of an Itinerant Director, which started at BAMPFA last weekend and runs through August 28. Frequently drawn to societal outcasts as a dramatic focus, he himself resisted easy categorization, seeking location shoots over studio soundstages wherever possible, sometimes using non-professional actors, refusing to eke hand-wringing melodrama from serious themes. He managed to make over 160 films (many now unfortunately lost) over several decades’ course before his demise in 1966.

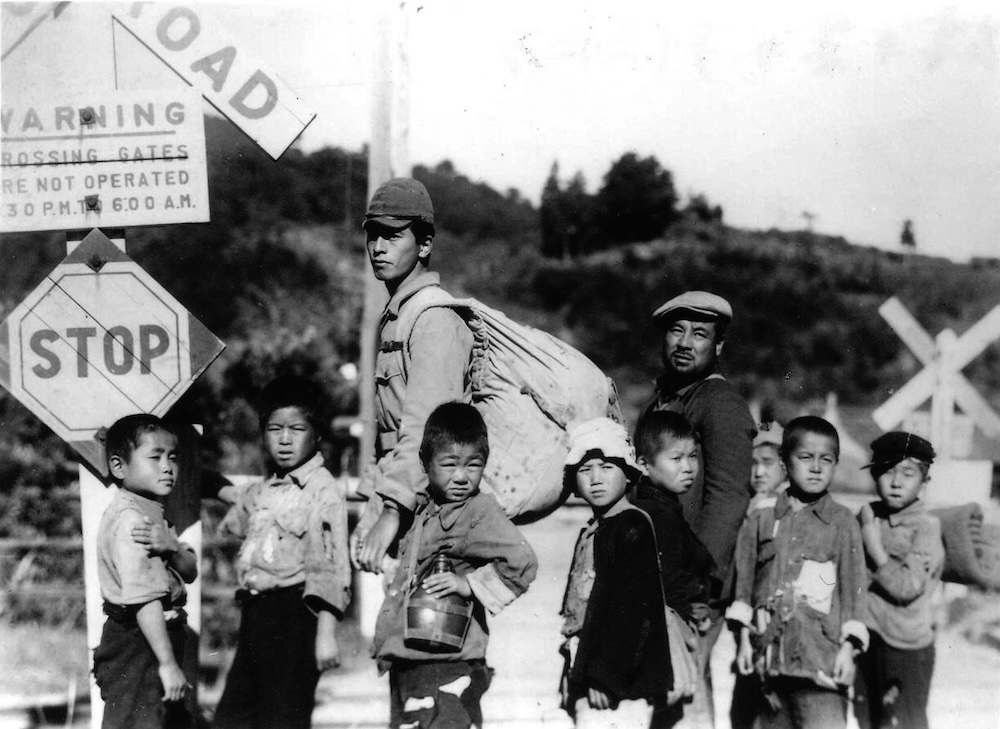

This weekend brings 1937’s Forget Love For Now (on Sat/27), which like the late-era silent A Hero of Tokyo (playing Wed/31) portrays women condemned for the less-than-respectable employment they’re forced into to support their fatherless families. Shimizu was particularly noted for his fond, naturalistic use of child performers. Children in the Wind (Aug. 9) was enough of a hit to generate a sequel, Four Seasons of Children (Aug. 11). After the devastation of WW2, he returned to that theme with 1948’s Children of the Beehive, a remarkable road drama in which a group of orphaned grade-school boys follow a rather stony Pied Piper of a discharged soldier around the country, seeking (even in a wholly destroyed Hiroshima) some foothold on a stable postwar life.

Later films in the series are the small-town comedy of manners Mr. Shosuke Ohara (1949, Aug. 18) and 1957’s Dancing Girl (Aug. 28), with sexpot Machiko Kyo (Rashomon, Teahouse of the August Moon) as a cheerfully amoral youth who scandalously upends the life of a sister and her husband.

Singularities: Eno, Mailer, Mountain Queen

A trio of new documentaries pay tribute to three driven personalities who stubbornly refused to go with the general flow.

Jeff Zimbalist’s How To Come Alive With Norman Mailer profiles the late author-celebrity who before his 2007 demise accumulated multiple Pulitzers, eleven best-sellers, a failed mayoral campaign, several terrible movies, six wives, nine children, a booking for felonious assault (he stabbed someone), a stint at Bellevue, and other emblems of an image as “the bad boy of American letters” that he both constructed and resented.

Admitting “I adore shocking people,” Mailer most definitely did not want to be a “nice Jewish boy from Brooklyn,” and he spent much of a long, colorful life rebelling against that birthright. His writing, alternately brilliantly incisive and showily self-indulgent, has somewhat fallen out of literary fashion. But this entertaining, even-handed documentary makes a good case for his lasting cultural importance, not least as a vehement opponent of the rigid discourse he called “psychological totalitarianism in American life.” Imagine his bellowing rage at the state of things today.

Practically an introvert by comparison, yet an object of fascination for his work in various media over the last 50-plus years, is the subject of a second nonfiction portrait opening at SF’s Roxie Theater this Fri/26. Gary Hustwit’s Eno. roams freely through the career of the erstwhile glam rocker in early-edition Roxy Music, the founder of “ambient music” as a genre, producer to U2, Talking Heads, John Cale, Laurie Anderson, Devo, Peter Gabriel, Grace Jones, Coldplay, et al… not to mention his innovations in technology, video art, and so forth. He calls himself a “futureologist” and “dabbler,” opining “Art is a way we synchronize our feelings about things.” Notable past collaborator David Bowie is seen saying “I’m not quite sure what Brian does… it’s more a kind of philosophic content.”

What you don’t necessarily expect from Brian Eno is that he be quite so unpretentiously fun. As seen here, he’s a great interview (and lecturer), and the wide range of archival clips is enormously enjoyable in itself. My only quibble with Hustwit’s film is its gimmick, which reportedly persuaded the subject to participate in the first place: The feature is intended to be shuffled like a deck of cards (or Eno’s own “Oblique Strategies” deck) for every showing, so the overall length as well as editorial order is different each time. That would be fine if it didn’t mean that sometimes you just get less—when I saw it at the Palace of Fine Arts a couple months ago, it was half an hour shorter than its apparent maximum possible running time. And that is rather maddening, since all the footage here is pretty much gold.

A different kind of role-model inspiration is afforded by Lucy Walker’s Mountain Queen: The Summits of Lhakpa Sherpa. Its principal figure was the first Nepali woman to survive summiting Mount Everest, and since has held her gender’s record for the number of times she’s repeated that feat. It was a considerable achievement for an uneducated villager born in a poor family of 11 children.

But this chronicle (which opens at the Opera Plaza Fri/26, then premieres on Netflix July 31) finds her facing greater adversities in relocating to the US with the fellow climber she married, Romanian expat George Dijmarescu. He turned out to be an abusive personality, and when his ample character flaws—which sometimes risked the well-being of other climbers—got publicized in a damning book (Michael Kodas’ High Crimes), things only got worse for his beleaguered wife and daughters.

In the present tense here, Lhakpa toils at a New England Whole Foods to support her family, while dreaming of a return to Everest—which she eventually achieves, logging her tenth summit in 2022. She’d divorced Dijmarescu, who subsequently died of cancer, seemingly mourned by few. Still, at times this film seems one-sided and simplistic, using him as a villain without his having any input, its heroine’s still very tentative command of English another roadblock to deeper understanding of a complicated life.

There’s also zero address of all the problematic issues around Everest (environmental degradation, too much reckless exploitation of under-prepared rich tourists, etc.) that other studies like High Crimes or Jon Krakauer’s Into Thin Air have exposed. Nonetheless, those looking for a rousing exercise in real-world uplift will very likely find Mountain Queen thoroughly satisfying.

Warning: Do Not Mess With Wood Sprites, Population Control, Mother Nature, or Things

Two new and two old horror-adjacent features also do their damndest to stand out from the crowd, although results certainly vary.

Based on a well-received novel by Andrew Michael Hurley, Daniel Kokotaijo’s Starve Acre has Matt Smith and Morfydd Clark as a young couple who move to rural Yorkshire in the 1970s, hoping the environment will calm their sometimes problematic pre-adolescent son. But instead his behavior only grows worse, until he dies during some sort of seizure. We suspect this may be connected to local superstitions, something confirmed when the husband digs up a hare skeleton, which then reconstructs itself to fleshy, furry, sinister life. This handsome-looking exercise in folk horror is meant to be bizarre and disturbing, but there isn’t enough suspenseful atmosphere to compensate for the choppy narrative, making the whole confusing, silly and a bit dull instead. It opens in limited US theaters and on VOD platforms this Fri/26.

Another offbeat misfire is Humane, the first feature from Caitlin Cronenberg, daughter of famous director David (whose son Brandon has also made several films, like last year’s Infinity Pool). In the near future, extreme global food and water shortages have forced drastic measures: Each nation has one year to “reach their population reduction goals” before international borders can re-open, necessitating programs of suicidal sacrifice. Veteran TV newscaster Peter Gallagher and spouse Uni Park invite his four squabbling, variably estranged adult children to dinner for some serious related news.

But when what was planned as a dignified farewell gathering goes awry, the irksomely dysfunctional “kids”—a bitchy corporate control freak (Emily Hampshire), sneering neofascist (Jay Baruchel), mercurial barely recovered addict musician (Sebastian Chacon), and petulant aspiring actress (Alanna Bale)—are soon at each other’s throats, rather literally. Placating no one is the arrival of a government enforcer (Enrico Colantoni from Veronica Mars and Just Shoot Me) who doesn’t care who dies, so long as he gets the number of corpses the family is now contractually obligated to provide. What starts out like a variation on the Purge movies turns into a shrill mix of one-dimensional characters, cartoonish political messaging, and weak black comedy/suspense elements, with Cronenberg unable to nuance the crude satirical bullet points of Michael Sparaga’s script. Humane begins streaming on Shudder this Fri/26.

More enjoyable in their very different, bizarre ways are two cult movies making one-shot appearances at Alamo Drafthouse New Mission next week. July 31’s “Weird Wednesday” choice is Colin Eggleston’s 1978 Long Weekend, which is not to be confused with an apparently poor recent remake starring Jim Caviezel. This memorably stark, ambiguous parable follows a noxious Australian yuppie couple (John Hargreaves, Briony Behets) who decide to glamp in the countryside. Shooting, littering, arguing, and otherwise pissing off their unspoiled surroundings, they find Mother Nature can only take so much—and her wrath is no joke.

Nothing in the world can prepare you for the flabbergastrousness of Andrew Jordan’s 1989 Canadian Things, which plays the prior evening’s “Terror Tuesday.” This no-budget exercise in WTF has co-writer Barry J. Gillis (whose own directorial exercises are also, um, unique) as one of three young Canuck hosers in for a casual night of brewskis, stoner dialogue, Satanic incantations, occasional glimpses of porn star Amber Lynn on TV as a news reporter, and giant mutant spider babies. A Super 8 epic both inspirational and amateur, mind-melting even when it’s just kinda dull, Things is one of those films you can’t quite believe got made—let alone released, to an actual public.