It all ended with a massive, boisterous, drunken wake on a late Sunday night. On January 7, the last hurrah for the much-beloved Uptown bar on Capp and 17th Street, hundreds crammed into the storied, rugged quarters for a sad yet joyous tipsy adieu, finished with a round of shots on the house and an emotional speech from one of the worker collective’s longtime owners as the clock neared 2am.

“Thank you for thirty-fucking-nine years of community,” Uptown co-owner Shae Green told the crowd from atop the old wooden bar, which since 1984 had welcomed and served all comers thirsty for libations and camaraderie. “How can you quantify that? There are so many people who made this community, and we thank you and we love you.”

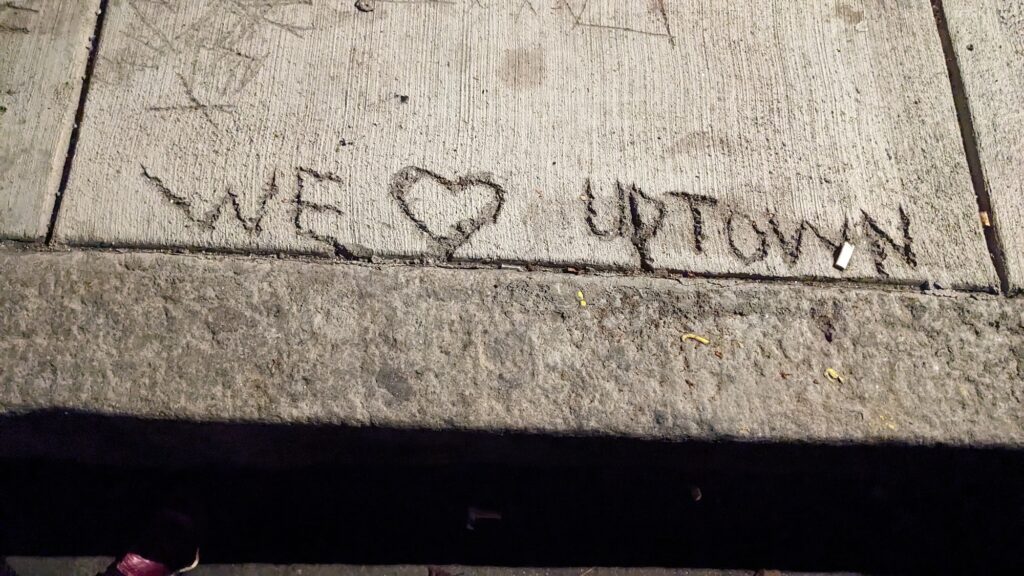

The late-night crew toasted and cheered the bartenders, who gave a special shout-out to Uptown’s longtime custodial worker, Florinda, who since 1989 had cleaned up after the bar’s nightly spillage. Finally, at two, there were no more last calls except to get the F out, and we tumbled out onto the Mission sidewalks. A fiddler and banjo player regaled the leftover crowd as people sighed, laughed, cried, and hugged goodnight and goodbye.

It was a fabulously diverse scene. Several younger folks, including one of the bartenders, donning keffiyeh in solidarity with Palestine. Weathered middle-agers like me (and older), sported outfits ranging from blue-collar work shirts and jeans, with keychains at the hip, to punk and goth looks. It felt like San Francisco in the early 1990s, when the Uptown first welcomed me into its lovably crusty clutches. Back when my rent was $225 a month. “This was the bar for the artists, punk rockers, other musicians, and political activists,” my old friend John reminded me.

As I leaned into the bar to shout my order, a friendly bearded fellow named Mike shared his thoughts from visiting Uptown for 13 years. “I’ve worked as a bartender since I was 20, I usually don’t go to bars,” he said. “We’re losing a lot of community here. This one hurts.”

Ed, a relative newcomer who’d worked the bar for the past three years, reflected on “the weird fucking people who came here…. There’s nowhere else I’d work. I’ve never bartended before. I only worked here because of this place and these people. … you can’t recreate a dive bar—I mean, the fucking holes in the floor?”

Jennie, a longtime bartender for Uptown, said: “This was the first bar I ever went to, and the best bar I ever went to.”

Uptown’s feisty history

Uptown has been a purposefully divey, gritty yet welcoming Mission District staple since 1984. According to a history that the owners recounted in city planning documents, Uptown “was born on Boxing Day in 1984 when founder G. Scott Ellsworth (Scott) closed escrow and got keys to the front door. He put word out to his friends to come down and celebrate, and they drank and fested all night until Scott flew to Chicago the next morning for his grandmother’s funeral.” The Mission spot “is believed to have housed a neighborhood bar continuously since its construction in 1910.”

By all accounts, Ellsworth made Uptown an inclusive and inviting space for the neighborhood, his amiable and erudite ways establishing the bar as a hub and a home for everybody—artists and musicians, activists and organizers, anyone looking for community.

“Scott encouraged spirited conversation and debate and impromptu performances by the bar’s many artistic and musical patrons, and the bar featured the work of local painters and craftsmen on its walls. Uptown became a favorite location for reading and discussion groups on weekend afternoons and in the early evenings.”

Scott became known as “the mayor of Capp Street,” helping neighbors in need, opening his bar all day, even when business was slow, for those needing a place to hang out, and getting trees planted along the street’s famously begrimed sidewalks.

The story of Uptown is in many ways the story of San Francisco, particularly the volatile cocktail of gentrification and cultural and political resistance in the Mission District. That same block is home to light industry and sidewalk auto repair joints; the Mission Neighborhood Resource Center, which provides healthcare and respite to homeless and poor folks; and many lower-income tenants.

When Uptown opened its doors in the mid-1980s, the Mission “was grittier and more diverse… home to many artists and musicians because of its relative affordability, and to many working people,” the owners’ history describes. When I arrived here in 1991, after a few days of clipping phone numbers off rental flyers in the old Rainbow Grocery on Mission and 15th Street, and pumping quarters into payphones, I landed a small but habitable room on 19th Street and Valencia for that now unbelievable $225 a month. A few months later, I moved into a bigger, nicer room with windows, for $250. Back then, you could work odd jobs, rent and eat cheap, and spend many of your hours exploring The City, writing and reading poetry, making music or art, immersing in politics—and doing much of this at Uptown.

For years, I met journalistic and political comrades here, toting our Mission burritos to accompany Uptown pints. Sometimes we’d occupy a cushiony Naugahyde booth alongside windows protected by black metal bars twisting like licorice sticks; often, we’d pile onto those old tortilla-scented, liquor-soiled couches under that towering painting in the back, “a bizarre rendering of an Elvis-like man playing pinball in an imaginary Uptown,” as the ownership team described it in their application for legacy business status, which they received in 2019. We’d talk lefty politics and journalism for hours, dishing on structural inequality, gentrification, and other maladies of late-stage capitalism.

As tidal waves of gentrification washed over the Mission and other parts of the city, through the later 1990s and much of the 2000s, residential and commercial rents skyrocketed, thousands of renters were evicted for profit, and many neighborhood businesses went under. Uptown survived, riding the waves and staying true to its unvarnished, down-home ways, “an anchor to the Mission’s past, yet also a beacon to a future in which the past would be remembered, not eviscerated,” the owners wrote.

When the Lexington Club closed after losing its lease in 2015—at the time, the “last remaining lesbian bar in the Mission”—Uptown hired some of its bartenders, welcomed its regulars, and for years hosted “Uptown Homos,” a reunion party for Lexington Club’s community.

Grit versus greed

When Ellsworth passed away in 2014, his sister helped a group of longtime Uptown bartenders form a new ownership team to keep the bar alive.

As 48 Hills reported at the time, “In one of his last posts on Facebook, Scott said, “My sense of humor is kind of dulled these days since I’ve been in a nasty legal fight with the avaricious asshole who bought the Uptown building, he’s trying to take me to the cleaners, jacking the rent 34%, though my lease limits it to 10%.”

The building’s owner, Kaushik Dattani, had acquired it six months before Ellsworth died, and pushed aggressively for higher rent, beyond what the lease called for, several Uptown owners and bartenders noted. As one co-owner put it, while wishing to remain anonymous: “In the end the Dattani’s ownership foretold the end of the Uptown. We were kind of bled out.”

The combination of soaring rent and the COVID pandemic brought existential demise. Manager and co-owner Tymmy-Jane Butler ascribed the closure to “COVID and greed.” Co-owner Shae Green told me they secured many government loans and grants, but eventually the money ran out while the rent kept going up. As Green told Mission Local, Dattani kept collecting the whopping $11,000 a month rent throughout most of the pandemic, “except for the equivalent of a month and a half,” even when the bar was shut down. “There were times when we were paying full rent with zero income.”

In added insult, Dattani is applying for a liquor license for a business name strikingly like that of an engraving in the location’s wooden bar of the word Kito—a portmanteau of the former owners’ names (Kim and Toni) back when the spot was a lesbian hangout called Macantes—but with the spelling Kiito.

Fittingly, the final night’s clientele included veteran housing activists and community organizers who’ve fought skyrocketing rents and tenant evictions, As the Anti-Eviction Mapping Project documented, Dattani has evicted dozens of city residents; I don’t mind disclosing that I protested some of Dattani’s eviction attempts as a co-founder of Eviction Free San Francisco.

“I had the pleasure of kicking him out of our bar one night,” recalled one longtime Uptown bartender. “He was always in our ear saying this should be a fancy cocktail bar…. If we had a different landlord, we’d still be open.”

Last call: “You could love here”

On that final night, Uptown lived and breathed again for the ages, stuffed to the gills with a wild, loud, kind-hearted, rebellious crowd that’s left its echoes in the old wood paneled walls, the decades-scuffed bar, the chipped and pockmarked floors, and those bathrooms lacquered with timeless layers of graffiti, paint shmears flecked about, almost like an amateur Jackson Pollock knock-off.

The bartenders kept ringing the bell and pouring drinks. They ran out of most beers and started handing out cans of Hamm’s here and there. A fiddler and banjo player kept the sidewalk festively musical. It was still the old Uptown, joyously full of life in the most democratic sense, and an old neighborhood corner pub.

And, oh damn, this old neighborhood space so many of us loved so much, for so long, is now no more. Another icon of a different era in this town—when rents were actually affordable, we had two (sometimes even more) big weekly papers, and the city’s culture and economy had space for places like Uptown, and its richly weird, dissident, rancorous clientele—sliding into the ether of history.

Though it’s worth adding, I’ve heard rumors they’re working on bringing Uptown back. As one bartender told me, “The heart of Uptown will live on, we just don’t know where.”

As a final(ish) honorific toast, I’m reminded of a poignant and probing poem by the great Richard Hugo, “Milltown Union Bar:”

You could love here, not the lovely goat

in plexiglass nor the elk shot

in the middle of a joke, but honest drunks,

crossed swords above the bar, three men hung

in the bad painting, others riding off

on the phony green horizon. The owner,

fresh from orphan wars, loves too

but bad as you. He keeps improving things

but can’t cut the bodies down.

You need never leave. Money or a story

brings you booze. The elk is grinning

and the goat says go so tenderly

you hear him through the glass. If you weep

deer heads weep. Sing and the orphanage

announces plans for your release. A train

goes by and ditches jump. You were nothing

going in and now you kiss your hand.

When mills shut down, when the worst drunk

says finally I’m stone, three men still hang

painted badly from a leafless tree, you

one of them, brains tied behind your back,

swinging for your sin. Or you swing

with goats and elk. Doors of orphanages

finally swing out and here you open in.