If you missed last weekend’s SF Electronic Music Festival (or not), there’s even more groundbreaking experimental performances flooding this weekend’s 28th Other Minds Festival, Wed/25-Sat/28 at Brava Theater, SF—which is stacked with fascinating-sounding new musical gems. Where else can you hear a piano-percussion quartet perform a response to the collapse of the world’s insect population, an electronic juxtaposition of expressionistic noise music and Japanese poetry, a piece that conjures “the magical sense of disorderliness,” and an abstract saxophone improvisation entitled We Say NO to Genocide?

Bay Area-based global new music community Other Minds, co-founded by Charles Amirkhanian and Jim Newman, launched its festival as a scrappy experimental performance gathering in 1993, born out of a Santa Cruz retreat that included contemporary music legends like Philip Glass, Meredith Monk, Conlon Nancarrow, Trimpin, and Julia Wolfe. It’s since expanded into a music label, podcast, weekly KALW radio show, performance series, and invaluable archive of Bay Area new music performance and discussion that I have gladly spent many hours of my life to exploring.

The festival is always a gathering of fellow, well, other minds—those who yearn for sounds that push the envelope while also being quite breath-taking in their own right. (Last year I swooned over nonagenarian electronic music pioneer Morton Subotnick’s performance of As I Live & Breathe.)

This year’s fest kicks off with two nights (Wed/24 and Thu/25) showcasing the return of musical kinetic sculptor Trimpin, who premieres his new piece with storied choreographer Margaret Fisher, The Cello Quartet. The piece features three autonomous cellos perched atop moving platforms. The word “cello” here hardly describes these sculptures, which will function both as instruments and dancers. A human cellist, Seattle’s Lori Goldston, also equipped with her own moving platform, will round out the quartet while a trio of circus artists, will interact with the moving instruments. There’s also a grand piano in there somewhere.

I exchanged emails with the Fisher about the project, and just how she choreographed circus performers to autonomous and human-powered cellos. A storied performer and pillar of the Bay Area scene, she’s been making revelatory work since the 1970s that often “pairs gestural choreography to experimental visual theater characterized by a cartoon aesthetic,” in the words of longtime Bay Guardian dance critic Rita Felciano.

Her company MAFISHCO was formed in 1984 “continue the revolution in cross-disciplinary artistic forms that came of age at the artist-run alternative performance space Cat’s Paw Palace from 1973-1977,” producing theatrical and sonic events value saturated motion, light as object in flux, unpredictable combinations, and degrees of tension that create “the strongest perceptions of a space in time.”

Wonderfully, our conversation wandered through her extensive artistic career. Along the way, we touched on her Bauhaus roots, medieval Arabic philosophers, the Jungian “community of the dead,” AI and the Divine, her participation in the first art-satellite communications project, and her own robotic invention, “Birdie.”

48 HILLS Thank you so much for corresponding with me, Margaret. I’m so curious: What was the spark of inspiration for your work on The Cello Quartet? It obviously comprises incredibly unique elements, beyond the “wow” of Trimpin’s mechanical inventions.

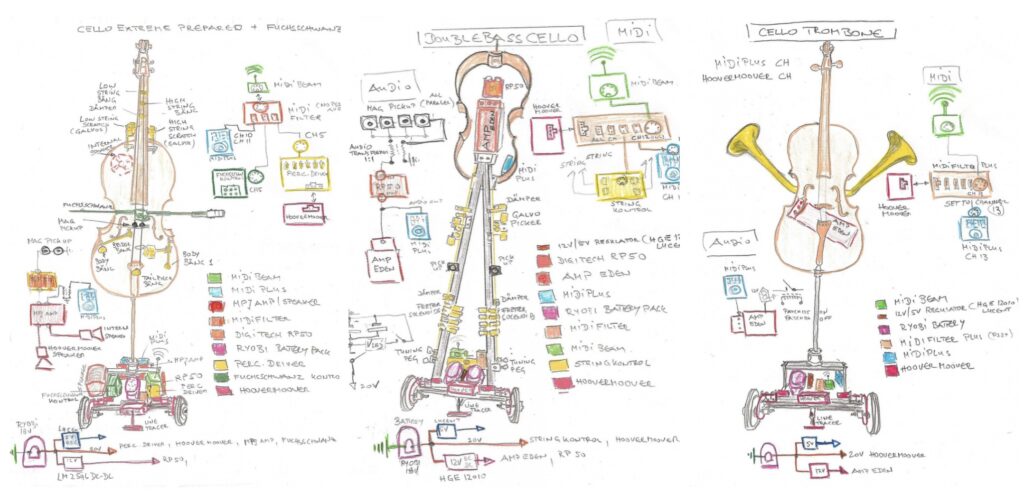

MARGARET FISHER I was asked to join the project the Fall of 2022. Trimpin sent Other Minds numerous drawings of his three robotic instruments, player piano, and the cello mobile for live cellist. He designed and fabricated complementary costume elements to be worn by dancers, referencing a Bauhaus/Triadic Ballet sensibility. After he finished the music for the work, he was in touch with me. This was March 2024. During the stretch of time I had to digest his developing ideas, with the understanding that I would be rehearsing long-distance with Trimpin’s instruments, robots, and costumes. I thought that circus performers and their actions would help convey the humor embedded in the work. Charlotte is the cello who saws herself in half—is that tragedy or comedy? Circus will often incorporate both. I’m also banking on humor being a good foundation for adaptability to the unknown, given our two teams will meet up just a few days before the performance.

Before that happens, another meet-up is unfolding here in Studio 16, the MAFISHCO home base in Emeryville —Circus meets Performance Art. I did not understand that asking circus artists not to be at the center of attention was a new idea. Our wonderful circus consultant Jeff Raz, founder of the Clown Conservatory, and star of the Pickle Family Circus, Cirque du Soleil, and Flying Karamazov Brothers, has been invaluable in helping us invent a fourth ring for circus. It wasn’t his impressive experience that convinced me I needed him. I heard him speak with infinite wisdom during an online interview and pegged him immediately as the Aristotle of Circus.

My own spark of inspiration is ancient. A spark of 20th-century modernism ignited in me at birth. My baby room was formerly my mother’s painting studio filled with abstract art. I grew up in a “Bauhaus” in Miami that my father built in the 1950s. As a young adult I followed the Russian Constructivists, the Ballet Russes, Nijinsky (above all!), the Dadaists, and Oskar Schlemmer’s Triadic Ballet in photographs, books, films, museum shows and reconstructions. My post-doctoral work concerned Italian Futurist Radio. (I understand radio was important in Trimpin’s formative years.) I hope this curated sensibility can do justice to those unique elements that are Trimpin’s alone.

48 HILLS At such distance and with so many elements in flux, how did you approach constructing the piece? Were there special spatial considerations, or ones of time?

MARGARET FISHER I prepared for Trimpin’s cello project even before knowing anything about it. During COVID lockdown and into 2022, I designed a robot, a modernist full-size heron that plays with floor toys, string puppets, and a cymbal. “Birdie” can shake their head with a dozen different rhythmic and sonic effects that ripple through the copper cones that comprise the long neck. Birdie was fabricated by Oliver DiCicco, an audio engineer and sonic sculptor, with electronics built out by Sudhu Tewari and Bryan Day.

I learned to program the robot’s movements through an exchange of daily emails—a “mail-order course” (remember those?) but customized for MAFISHCO. On the other side of this exchange was an anonymous, extremely generous, programmer and audio engineer who, requesting anonymity, responded to a question on a tech forum. I don’t know if Trimpin was aware of this robot when Charles Amirkhanian kindly suggested my name for the project, but Charles had seen the new work at Studio 16 previews and knew I had a left foot in dance, and a right foot in everything else—music, performance, robotics, video, research.

I saw Trimpin first in Peter Esmonde’s fascinating documentary about him, “The Sound of Invention,” and met him briefly at the Other Minds Festival in Fall 2022, but it was too early to discuss this new work.

Regarding spatial considerations, as a choreographer I look for relationships by adjusting the scale between the human form and objects, and by adjusting the vertical and horizontal orientations of the human form. An intervention in scale can upend expectations to create something fresh or something referring to the past but expressed in a different discipline. For example, I look at a lot of art predating and up into the medieval period for inspiration. By the time of the Renaissance, the painters in particular were representing scalar relationships with a high degree of realism in ways that reinforced the mathematics of spatial reasoning skills. I have worked with science and technology throughout my career to, alternately, seek out the incommensurability of things, rather than the science of things.

I did have spatial concerns. Trimpin’s developing plans began to form in my imagination as “everything but the kitchen sink.” I worried there would be no space on stage for dancers of any size if the robots are ambulatory – the cellos, the cello mobile, the baby grand. I learned, too late, by reading the publicity, that the dancers would influence the movements of these objects. We were collaborating long distance by phone, video, audio and image, and in no particular order, so a lot of detail entered the discussion out of order, at random, or by chance or secondhand.

I first suggested to Trimpin that maybe he didn’t need dancers at all, just good lighting. He insisted. Would the idea of circus appeal to him? I was rather nervous about suggesting this as I had no idea of how proprietary he might be regarding the look of his Cello Quartet.

Fast forward and I have the honor of working with three terrific circus artists and learning about their wonderful whacky world. Bri Crabtree created the travelling Silly Circus Show, specializing in juggling, magic tricks, unicycle, and more. Calvin Kai Ku is a magician, acrobat, and circus performer of all stripes who also works with the Medical Clown Project. Joel Herzfeld is a handbalancer and cyr artist—it will be more amazing for you to look that up than for me to explain it. He performs across the globe, land and sea (the cruises!), and has an interest in combining his work with opera.

My first impulses were to place an Odysseus–like figure who clings to the belly of the grand piano as it moves around the stage (piano substituting for the sheep in the ancient Cylops tale), to set up a ‘reveal’ in Movement 1, and to cast very young martial arts experts as the ‘dancers.’ These first ideas quickly evaporated as the piece developed. I don’t know if I even mentioned them to Trimpin. Having the crucial rehearsals and performances on school nights certainly contributed to my abandoning the idea of young martial artists.

Even if you try to connect the dots, from Odysseus to Aristotle to Bauhaus to Trimpin, there is no rhyme or reason as to why these circus artists are going to do what they are going to do in the Trimpin show. I’ll keep that a surprise.

48 HILLS You’ve been making innovative dances and performances for many years. Where do you feel this piece is situated in your body of work—does this feel like a new or different direction for you?

MARGARET FISHER Cello Quartet is definitely at one with the trajectory of my career that began in the 1970s. Trimpin has created, composed, and engineered the bulk of the material—the concept, visual design, music and instruments. I confess, it is liberating to not be the main artist. The long-distance collaboration is oddly do-able: Trimpin is based in E. Washington state, the cellist in Seattle, the costumer near Portland, one of the circus artists lives in Boston.

To answer with specifics, collaboration with composers is a natural for a choreographer. I’ve always asked musicians to join in the movement or performance tableau when possible. Among MAFISHCO past performances, Bob Hughes ate spaghetti at a camp table in our work Gli Insetti, while negotiating two walkie-talkies to create an ethereal sonic landscape of feedback. Charles Amirkhanian, Artistic Director of Other Minds, and I collaborated in 1979 to create Egusquiza to Falsetto, a work for the Arch Ensemble for Experimental Music (named after a volume of an encyclopedia.) The musicians were horizontal, which was notable, but my most vivid memory is that the size and geometry of a tent constructed for the percussionists put the scale of the human figure at odds with the construction, to bring their gestures into relief.

I doubt the audience saw this. They saw a water cooler, musicians with instruments, plaid blankets, a simulated nightmare and scream, a child scribe (Rita and Dick Felciano’s son Manoel—now a composer himself), and a vocal quartet reciting Charles’ text sound poetry. That makes me think that the trajectory of one’s career is somewhat like the double helix of DNA, the interest, concepts, sensibilities on one helix, the resulting artwork on another.

In 1984, I collaborated with Charles Shere to choreograph, design, and direct his opera based on Marcel Duchamp’s Bride Stripped Bare by her bachelors, even… The vocalists, John Duykers, Anna Carol Dudley, Judy Ruth Hubbell, and Barney Jones, all well known and well loved here in the Bay Area, balanced on a cantilevered platform somewhat like an enormous see-saw. Or they assembled elements from Duchamp’s painting on glass that had been built out into three dimensions for the stage. I performed a horizontal solo. In a later iteration, Jerry Carniglia pulled a grand piano across the stage with the pianist Eliane Lust—a nod to Buñuel’s Un chien andalou (1929), and presaging Trimpin’s piano and performer that will travel the stage together in Cello Quartet.

The horizontality, intervention in scale, and crossover of musicians to performance art are recurring themes in my work. The grand piano sort of joins that list. Sort of, because it is Trimpin’s work.

Regarding science and tech, I’ve adapted the 5th-century tale by Kalidasu, The Cloud Messenger, for two cloud chambers. I’ve incorporated vintage projectors and turntables, lasers, and the robot mentioned above. Richard Lowenberg sponsored my participation in Thermographic Video Cartoons, as well as the first bi-coastal real-time dance duet for Send/Receive, facilitated by NASA and resulting in the first art-satellite communications project.

48 HILLS With all the recent hubbub about autonomous cars and other technology, not to mention AI and its contentious relationship to the arts, it’s exciting to see human artists interacting with autonomous instruments at this particular moment. Do you feel this piece makes a larger statement on the contemporary relationship of art and technology right now?

MARGARET FISHER I am too much in the weeds to see beyond the immediate elements of the work. What I do look for are the relationships between the elements at hand. Ideally, solutions to practical problems arising from those relationships serendipitously provide the cohesion that hints at structural integrity, without that structure necessarily conforming to the rational world. This is the art. Whether there is a statement to extrapolate from it, I’ll leave to others, because at that point the artwork is turned into something constrained, rather than set free by reason.

The eighteen months prior to joining Trimpin’s project was a period of grief during which I coped by investigating what Jung calls ‘the community of the dead,’ through religion, philosophy, and poetry. The medieval Arabic philosophers posited an Active Intellect or Agent Intellect (in translation of course)—I take this to be a divine pool or gathering or dimension beyond the limits of knowledge in the real or lived world. Of what? Souls? Intelligence? Information? The AI is situated between life as we know it, and the Divine as we imagine it, trust in it, or deny it. And that’s the kind of AI that really rolls my socks up and down.

28TH OTHER MINDS FESTIVAL Wed/25-Sat/28 at Brava Theatre, SF. More info here.