Bad history — even when well-intended — gives me a headache, because it so often misses and conceals far more important truths. To wit, in a recent column David Talbot neatly summed up the conventional-wisdom Legend of “Negro Removal” driven by the city’s Redevelopment Agency decades ago:

“Now that Iris Canada has joined the thousands of other African Americans who’ve been banished from the city, the mayor can put up a statue in honor of the centenarian. Maybe it can be erected in Justin Herman Plaza, named in celebration of the redevelopment czar who evacuated San Francisco’s black population in the 1960s.” (San Francisco Chronicle, February 13, 2017).

Uh, no. In 1950 San Francisco’s African-American population was 44,000. it grew to 74,000 by 1960, 96,000 by 1970 – its all-time peak after redevelopment demolition was mostly finished – and then back to 86,000 in 1980. Plainly, there was not an “evacuation” while Justin Herman was alive (he died in 1971) or soon after. The long-term citywide decline in the city’s African-American population since 1980 is a result of different realities, another story, but not this one.

What actually happened to the one-time African-American Fillmore community is more complex, and very important to fully understand in its own right. The Western Addition Redevelopment Project embodies this story.

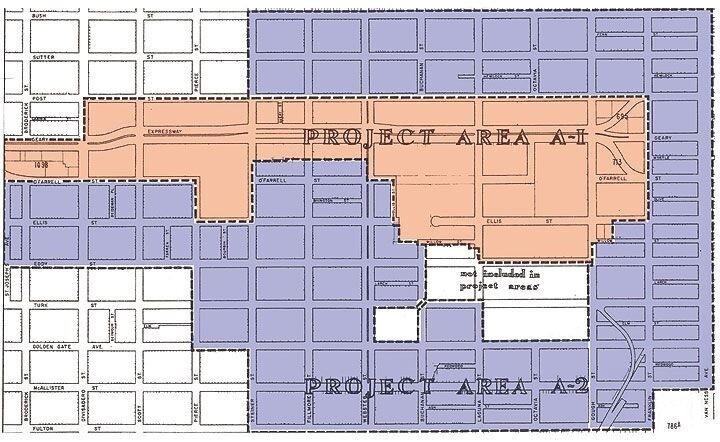

First, it is absolutely essential to know there were two very different Western Addition Redevelopment Projects – the A1 Project of the 1050’s and the A2 Project started in the 1960’s, and completed in the 1990’s.

The A1 Project: Bulldozer racism

The city’s historically racist all-White-(male) power structure of the 1950’s – its elite industrialists, financiers, and hosts – saw the rapid growth of its African-American communities that had begun during World War II as a very dangerous threat. The negative consequences of post-war suburban out-migration and de-industrialization of the nation’s central cities were becoming apparent, and this leadership feared its economic impacts on San Francisco. That macro-trend became conflated in their minds with its outcome (but not its cause), the resulting localized economic urban disinvestment it led to – “blight” as it was called by the urban planners of the day. “Blight” was a pseudo-metric city leaders applied to formally designate poor city neighborhoods throughout the nation as slums that needed “clearance” and rebuilding as new “modern” communities. As if that would reverse suburbanization or at least magically “stabilize” inner cities (i.e., the White people would stick around).

So after surveys in the early 1950’s, the city’s newly-established planning department identified two “blighted” neighborhoods – central South of Market where the skid-row “bums” lived (“threatening” somehow the viability of the Central Business District), and the Fillmore District. The Fillmore was a typical city neighborhood that had suddenly become the business and social center of the city’s new and expanding Black population during and after the war (thanks in part to the blatantly racist seizure, removal, and internment of the Japanese-American residents of adjacent Japantown).

What may have most alarmed the city’s elite was that the Fillmore was only five blocks away from California Street – the southern edge of their own bastion of elite social privilege, Pacific Heights. Those Black people were getting close!

So in response, with little opposition, in 1956 city Hall approved San Francisco’s first federally-funded redevelopment project, the Western Addition A1 Project. The city’s newly-elected Republican Mayor, George Christopher, pledged its rapid implementation. It had three stated main goals:

- To create a new high-capacity Geary Expressway from Van Ness Avenue to Divisadero Street to address the citywide traffic congestion that had become a top priority civic quality of life issue since the war (thanks of course to the great new bridges that allowed suburban commuter auto traffic to pour into the city).

- In general, to demolish the project area’s “blighted” housing – including its hundreds of Victorian apartment buildings – with “modern” new apartments.

- In particular, to somehow “modernize” Japantown and create a focus of commercial development along Van Ness Avenue.

But beneath this superficial urban planning cover, the real A1 Project agenda was brutally cynical racism in civic action:

- To stop the northward expansion of the Fillmore’s African-American community and contain it south of Geary Street. The new eight-lane Geary Expressway was its de facto physical barrier – a symbolic moat, complete with Fillmore Street draw bridge.

- To put in place a small Asian-American community buffer zone, the renewed Japantown, physically in between Black and White neighborhoods.

By 1960 almost 2,000 African-Americans were displaced by the demolition of their homes along Geary Street and to its north. Yes, they were “removed” from their homes and businesses, their communities torn apart. But they were not driven out of the city, or even very far. Instead they were able to move into adjacent neighborhoods – Divisadero, Hayes Valley, Lower Haight, and the Haight Ashbury – where apartments were readily available due to the concurrent rapid suburban outmigration from those White neighborhoods.

Demolition of the A1 Project area was completed by 1960 and the Geary Expressway opened in 1962. But the promised new property development failed to materialize, and civic dissatisfaction with the Redevelopment Agency grew. In 1959 Mayor Christopher hired Justin Herman, the head of the local U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development office, to take charge. He immediately began to plan for its expansion, the A2 Project.

The A2 Project: Deluded hubris

The absolutely last thing the 1960’s Democratic/Labor Party of San Francisco wanted was to push African-Americans out of San Francisco, because without their voter support it had no hope to win City Hall. That was never the agenda.

Joseph Alioto represented a new generation of national post-war big city politics, moderate Democrats who forged political alliances with selected Downtown leaders, usually real estate and development interests, and combined that with traditional labor union and Black voter support. Alioto was a member of the Redevelopment Agency Commission when it approved the A1 Project, and later was instrumental in recruiting Justin Herman as its head.

Thanks to the growing Black vote, the very liberal Congressman Jack Shelly was elected Mayor in 1963. By then Herman and Alioto had the proposed A2 Project plan ready for approval, and despite serious reservations about its potential community disruption Shelly agreed to its approval in 1964. By this time there was strong African-American community opposition, and litigation delayed its start until 1967. But the project finally went ahead and demolition started.

The national conception of “urban renewal” at this time was premised on intellectual hubris and analytical blindness (intermixed with ubiquitous real estate development profits). A generation of “visionary” uber-planners – modeled on the transformative legend of New York’s Robert Moses – proselytized that entire new robust modern urban communities could be rebuilt on the “tabla rasa” of demolished city slum districts. Edward Logue in Boston, Edmund Bacon in Philadelphia, and others achieved national recognition in this role, and Justin Herman aspired to join them. The Golden Gateway Project’s conversion of the city’s Produce Market into an office and residential skyscraper complex, first approved in 1958, was intended to be his signature downtown exemplar, and the Western Addition Project his in-city realization of idealistic “new town” planning.

None of this generation of urban planners and civic leaders fully grasped the fundamental reality we have learned from their mistakes: Once a community, a neighborhood, is physically destroyed and its people and businesses scattered – its “social capital” lost – no planned new development can ever reassemble and put it back, even if they sincerely try. That is impossible.

Herman and Alioto did want to somehow restore the African-American Western Addition community after they tore it down. Alioto needed its votes when he pushed Jack Shelly aside and ran for mayor in 1967, and for re-election in 1971. So Herman took full advantage of the new low-income housing programs initiated by President Lyndon Johnson’s “War on Poverty” to fund construction of multiple affordable garden-apartment complexes in the Project area.

The Western Addition Redevelopment Plan that finally evolved in the 1970’s from all these influences was a mixture of disjointed agendas. High-density residential and commercial developments were built sporadically on Cathedral Hill and Van Ness Avenue. An ambitious Japan Center was built on the north side of the Geary Expressway, which still divides the communities psychologically as well as physically. The intended neighborhood retail core focused on Fillmore Street never quite achieved critical mass or identity.

The Western Addition Project also provided something else very important to City Hall: bountiful political patronage targeted especially to African-Americans – jobs, contracts, appointments – who supported Mayor Alioto. By the 1970s, redevelopment had become very controversial in San Francisco, and this political “community” base was often brought to the fore by its proponents to defend it.

But still, far fewer new homes were built than the many thousands of displaced Fillmore residents needed, and so many never could use the “Certificates of Preference” they were given to symbolize their right to return to their community.

The city’s overall population was still declining in the 1970’s, but with the concurrent new influx of the young Baby Boom generation coming to San Francisco, practical relocation options were more limited than the decade before. Instead of the adjacent neighborhoods, many displaced families moved to the Bayshore District, and many adults moved to the Tenderloin. And without most of its former customer base, the Fillmore’s African-American business community could not re-establish itself even when retail spaces were finally built and economic assistance was available.

There is much, much, much more to the story of what did ultimately get built in the Western Addition A1 and A2 Project areas. But the final outcome, what is there today, is a slowly shrinking modest-sized African-American community concentrated in the those 1970’s housing developments, along with a few surviving Black churches and a scattering of small businesses. Japantown is essentially a relic community of themed businesses, but still holds cultural significance for Japanese-Americans. Most visibly, the Fillmore Street district has recently become a focus of the city’s Korean-American community. But overall, the Western Addition Redevelopment Area still feels … unfinished.

The Counterfactual: What if it had never happened?

What was the alternative future? Would the Fillmore’s African-American community have survived if it had never been displaced by redevelopment? What would be there today?

The African-American Fillmore community of the 1950s-1960s that was special, that is so fondly remembered, was a unique outcome of social and economic factors that no longer exist. Due to the widespread anti-Black housing discrimination throughout San Francisco, the Bay Area, and the nation that was the norm during that era, the Fillmore District was something very rare – a genuine mixed-income community. African-American professionals and businesspeople lived in the same small neighborhood with African-American blue collar and service workers, shopped at the same stores and attended the same churches. Their children went to the same schools and playgrounds. For this community, market capitalism’s inexorable geographic segregation by class and income levels was not possible. That created a community with a special spirit, united by a common bond, something wonderful.

But this mixed-income community would have gradually come to an end as anti-housing discrimination laws were passed in the 1960s thanks to the local and national Civil Rights Movement, and attitudes gradually changed in compliance. Black professionals and business people would have moved to single-family-housing neighborhoods and communities in the city and Bay Area they could afford, just like everyone else (as actually did begin in the 1970s, accounting for that decade’s drop in the number of African-American city residents). Renters could remain, but many would relocate to communities closer to their jobs elsewhere, just like everyone else. And the neighborhood businesses community that relied on this customer base would slowly shrink as a consequence.

We know this would be the case because it is the pattern that actually did occur in other inner-city African-American communities around the county of the same era that were never redeveloped. The least likely to move would have been the residents of the subsidized affordable housing. If the concentration of lower-income residents and economic disinvestment on Fillmore and Geary Streets were sufficient to become prominently visible, there would have been demands from the community for the city to address it (as in fact there repeatedly were due to the slow progress of Fillmore redevelopment in the 1980s and 1990s).

How City Hall would have responded to these trends is a guess. New community facilities would likely have been built. “Spot” redevelopment projects at specific locations intended to boost the African-American community probably would have been approved (as in fact the Redevelopment eventually attempted, the now-failed Fillmore Jazz Center). In recent years affordable housing development would have been encouraged. The best civic outcome might be that the neighborhood-dividing devastation of the Geary Expressway would never have happened, and Geary Street would be a lively retail district today.

But in any event, by now the gentrification of the Fillmore District would be extensive if not complete, just like the rest of San Francisco. The hundreds of Victorian apartments that were demolished would have been fully “revitalized.” The hip character of Hayes Valley and the Lower Haight would extend from the south, while the upscale feel of Upper Fillmore would certainly reach to Geary and likely have merged with or supplanted much of old Japantown.

Perhaps a remaining Fillmore District African-American community of today would be much like the Mission District’s Latino community now – fighting against market forces for its cultural survival in a changing San Francisco.

Conclusion

Some scars never heal.

It would also help if he spelled Mayor Shelley’s name properly.

Two sources, Whites who lived there (NOPA) on the same block as a couple of Black families before the War. I heard that story 30 years ago. They have since passed away. If they were still alive they would be in their late 90’s. I also knew a Black family that moved from NOPA to Miraloma Park (Sherwood Forest) in the 50’s but they did not say that. However, I know they would have moved to St. Francis Wood if not for racist restrictive covenants. They moved close by.

What’s your source for that?

Pointing out racism =/= being a racist.

Full on wars – esp on the 24 Divis bus too

There was also resentment as the Gay gentrifiers spread east from the Castro; I recall the Gay bashing.

The upper middle-class Blacks who were there (NOPA) before the war, we concerned they would be confused with migrants (“those people”) from the South. Despite still blatant racism that existed at the time, they were small in numbers and fit in comfortably. In the 50’s there were White middle-class neighborhoods in the City, like Miraloma Park, where they could move to get away. With housing discrimination laws in the 60’s they could move to even more places. The concern with “loss of community” was not really the issue. They moved for the same reasons everyone else, Irish, Italians, Scandinavians, moved from their communities.

As he pointed out, It was part of a national trend and occurred in Black communities in other cities without redevelopment. It was part of the “Second Great Migration.” Interesting, however, is that with gentrification, upper milddle-class Blacks are also moving into gentrified areas, like the Mission. The employed Black numbers in the Mission have increased from 612 to 825, a 35% increase, from 2010 to 2014. That is still a very small percent of the total, but is is growing. I would guess we will also see upper middle-class Blacks moving to the Bayview as it gentrifies.

I know two families that were displaced from the Fillmore; one moved to the Richmond District and the other to Miraloma Park where there was already a Black upper-middle class enclave. Before the War, middleclass Blacks lived in NOPA. Many of them left the area as Blacks from the South moved in; Black middleclass flight!

Redevelopment happened in the 60’s. The Black population increased by over 20,000 at the same time. The decline in the Black population after 1970 occurred in parts of the Western Addition not redeveloped. Redevelopment had nothing to do with the decline. It was part of a national trend, the “second great migration.”

I was puzzled. Thank you for enlightening.

Elberling’s essay is filled with interesting information, and presents a more nuanced picture of what happened to the Fillmore than is commonly found in progressive circles. But his claim that Justin Herman’s policies were not not instrumental in gutting the Fillmore because the black population reached its peak in 1970, a year before Herman died, strikes me hair-splitting and pedantic. The second stage redevelopment plan that Herman set in motion eventually did fatally undermine the black community, as Elberling acknowledges. So I accept his criticism that my sentence about Herman evacuating the community in the 1960s was not precisely enough worded. But my overall point is still valid. The policies that Herman BEGAN in the ’60s eventually destroyed the Fillmore.

For those who don’t know, “wypippo,” sometimes spelled “wypipo,” is a term racists use to imitate blacks talking about white people.

Photo marked “Geary and Post” should read “Fillmore, looking south at Post St”

Forgetting about gays & wypippo gentrifying the lower Haight, the upper haight, panhandle/inner Richmond (area around USF where a large # of AA lived/still live) & the resentment that the AA community had towards gays & wypippo in general is forgetting some history there. But in general, pretty good analysis.

Too bad the author never gets around to revealing the “far more important truths” concealed by Talbot’s “bad history.” Also, the use of “somehow” three times in an essay about history tends to undermine the credibility of the piece.

This is a very interesting read.

I noticed in minutes of community meetings of the time one topic which homeowners of Fillmore buildings to be demolished brought up again and again: inadequate compensation. Not the loss of their community and neighborhood, not being forced to move away, just that they were underpaid for their lost property. I suppose that was a practical matter of bringing up the one issue that might be legally enforceable. In any case, they didn’t get that either.

I also wonder, when thinking of ‘what might have been’, if there was a higher percentage of people owning their own homes in the Fillmore in the 1960s than there was of Latinos in the Mission in the 1990s.