I find it fascinating that so many publications are talking about the “party elite” and “Democratic leaders” who are trying to get President Joe Biden to bow out and not run for re-election. The reality is that the national Democratic Party “elite” is largely big donors who control the establishment and people who work with them.

Democrats argue that lot of people will suffer if Donald Trump wins in November—but those big donors aren’t among them. The very, very rich, particularly in tech and finance, who have become the elite of the party, are not going to lose their health insurance, or their retirement money, or become homeless.

There’s a really interesting story by Jason Zengerle in The New York Times Magazine this weekend about Rep. Marie Gluesenkamp Perez, who won what many consider the biggest political upset of 2022, winning as a Democrat in a traditionally Republican district in Washington State.

Perez, who ran an auto-repair shop before getting elected, has voted with the GOP on some issues; she opposed the student loan forgiveness program, in part because most of her constituents have no college degrees. Here’s what struck me:

Democrats have been working through the stages of grief about their loss of working-class voters for the past two decades. When George W. Bush was in the White House and Thomas Frank’s “What’s the Matter With Kansas” sat on every Georgetown bookshelf, the Democrats were in denial, complaining that right-wing Svengalis had hoodwinked the working class into voting against their own interests by plying them with contrived cultural grievances. Next came anger, the purest form of which was Hillary Clinton’s 2016 presidential campaign and her “basket of deplorables” label for Donald Trump supporters. After Clinton’s defeat came Democrats’ bargaining phase, as they tried to accommodate the rise of Senator Bernie Sanders and the belief that he, and politicians like Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, signified a latent interest in socialism among working-class voters. But in trying to defang Sanders and his fellow insurgents, the Democratic establishment tended to adopt only the most performative socially liberal policies while rejecting ones that might actually threaten or change the neoliberal economic regime. In the process, Democrats seem to have only alienated working-class voters even more.

I still believe Sanders would have defeated Trump. He also would have threatened the rich people who have been comfortably controlling the party since at least the Clinton era. (This happened in part because Ronald Reagan and globalization broke the labor movement; labor used to fund Democrats. So the party went to Wall Street instead.) Better to lose to Trump than risk Sanders.

Here’s George Monbiot in the UK Guardian, with a brilliant analysis of economic history:

What is the “normal” envisaged by pundits and politicians of the left and centre? It is the most anomalous politics in the history of the world. Consciously or otherwise, they hark back to a remarkable period, roughly 1945 to 1975, in which, in certain rich nations, wealth and power were distributed, almost everyone could aspire to decent housing, wages and conditions, public services were ambitious and well-funded and a robust economic safety net prevented destitution. There had never been a period like it in the prior history of the world, and there has not been one since. Even during that period, general prosperity in the rich nations was supported by extreme exploitation, coups and violence imposed on the poor nations. We lived in a bubble, limited in time and space, in which extraordinary things happened. Yet somehow we think of it as normal.

Those “normal” politics were the result of something known to economic historians as the “great compression”: a drastic reduction in inequality caused by two world wars. In many powerful countries, a combination of the physical destruction of assets, the loss of colonial and overseas possessions, inflation, very high taxes, wage and price controls, requisitioning and nationalisation required by the wartime economy, as well as the effects of rising democracy and labour organisation, greatly reduced the income and assets of the rich. It also greatly improved, once the wars had ended, the position of the poor. For several decades, we benefited from the aftermath of these great shocks. Now the effect has faded. We are returning to true “normality”.

The history of many centuries, including our own, shows that the default state of politics is not redistribution and general welfare, but a spiral of accumulation by the very rich, the extreme exploitation of labour, the seizure of common resources and exaction of rent for their use, extortion, coercion and violence. Normal is a society in which might is right. Normal is oligarchy.

In the US, the top rate of estate (inheritance) tax rose to 71% in 1941, and income tax to 94% in 1944. The National War Labor Board raised workers’ pay while holding down executive pay. Union membership soared. In the UK, the top rate of income tax was held at 98% from 1941 to 1952. It took decades to decline to current levels. A purchase tax on luxury goods was introduced in 1940, with rates that later rose to 100%. The share of incomes captured by the richest 0.1% fell from 7% in 1937 to just over 1% in 1975.

In the absence of one of the four great catastrophes, income and capital inexorably accumulate in the hands of the few, and oligarchy returns. Oligarchs are people who translate their inordinate economic power into inordinate political power. They build a politics that suits them. Scheidel shows that as inequality rises, so does polarisation and political dysfunction, both of which favour the very rich, as a competent, proactive state is a threat to their interests. Dysfunction is what the Tories delivered and Donald Trump promises.

And then this: Olivier De Schutter argues that the entire concept that underlies modern capitalism—the mandate of economic growth—is actually a ruse to help the very rich get even richer.

Economic growth will bring prosperity to all. This is the mantra that guides the decision-making of the vast majority of politicians, economists and even human rights bodies.

Yet the reality – as detailed in a report to the United Nations Human Rights Council this month – shows that while poverty eradication has historically been promised through the “trickling down” or “redistribution” of wealth, economic growth largely “gushes up” to a privileged few.

In the past four years alone the world’s five richest men have more than doubled their fortunes, while nearly 5 billion people have been made poorer. If current trends continue, 575 million people will still be trapped in extreme poverty in 2030 – the deadline set by the world’s governments to eradicate it. Currently, more than 4 billion people have no access whatsoever to social protection.

Hundreds of millions of people are struggling to survive in a world that has never been wealthier; many are driven to exhaustion in poorly paid, often dangerous jobs to satisfy the needs of the elite and to boost corporate profits. In low-income countries, where significant investment is still required, growth can still serve a useful role. In practice, however, it is often extractive, relying on the exploitation of a cheap workforce and the plundering of natural resources.

The politicians I trust and respect are the ones who entered this realm because they care about issues and causes—and understand that the movement is more important than their careers. I respect people who are willing to say that someone else might be more effective at a job that moves the agenda forward, who see elective office as a means to an end, not personal power and glory.

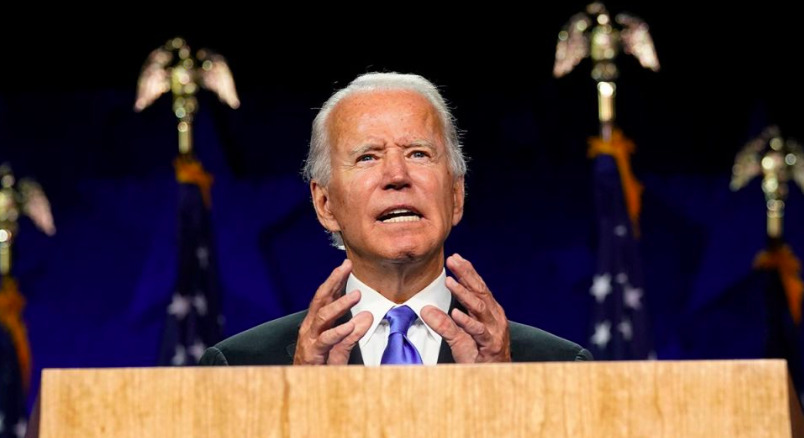

Biden may drop out. He may be replaced—with Kamala Harris, or Gavin Newsom, or Gretchen Whitmer, or someone else who will have similar politics. But it won’t be anyone who “might actually threaten or change the neoliberal economic regime.”

Which might mean that the three out of five voters who don’t have a college degree, and who have suffered and continue to suffer under neoliberal economics, will not be a loyal Democratic voter base.

The national Democratic Party doesn’t seem willing to talk about that.