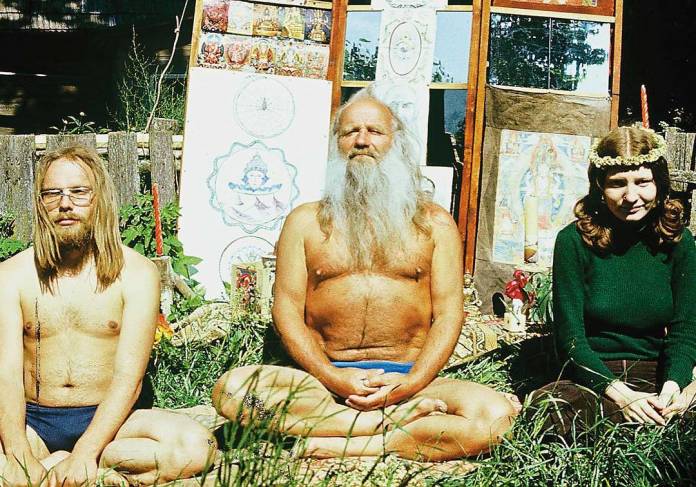

SCREEN GRABS It’s a week unusually full of documentaries, including the Roxie’s single showing next Wed/5 of Soviet Hippies—a look at countercultural resistance behind the Iron Curtain—and the return next Thurs/6 of the SF Green Film Festival.

Now in its eighth year, that leading showcase for environmentally focused cinema has expanded to nine days, and overlaps with the Paris Climate Agreement-supporting Global Climate Action Summit being held in the city Sept. 12-14. It encompasses some sixty films from twenty countries (shown at several different SF venues), their subjects including global wildlife preservation/extinction, indigenous peoples activism, pollution and its related health issues, “clean” industrial breakthroughs, innovations in the battle against hunger, and much more.

Of particular local interest will be Wilder Than Wild, which looks at recent California wildfires, their causes, and possible cures to this escalating crisis; Patrimonio, focusing on residents’ fight against against a “mega hotel/condo complex” development in Big Sur; as well as Nail House, about how the conflict between gentrification and poverty in SF is a microcosm of similar trends worldwide. Many filmmakers (well over half of the directors represented this year are women, by the way) will be in attendance at their screenings. For more info on the SF Green Film Fest, which runs Thurs/6-Fri/14 at various SF venues, click here.

Elsewhere (all opening Fri/31):

THE LITTLE STRANGER

British novelist Sarah Waters writes genre fiction of a very high order, finely crafted suspense novels often ambiguously colored with elements of the supernatural and/or lesbian attraction in repressive period milieux. But despite all clever plotting, her key strengths of atmospheric and psychological nuance aren’t ones that necessarily transfer ideally to the screen. (Probably the best and most famous prior Waters adaptation is Chan-wook Park’s acclaimed The Handmaiden, though her connection via source novel Fingersmith isn’t widely noted—no doubt because that film transfers its story almost unrecognizably from Victorian England to 1930s colonial Korea.)

However this latest from unpredictable Irish director Lenny Abrahamson (Room, Frank), adapted from Waters’ 2009 book, is the kind of happy surprise one hopes sticks around long enough to find its audience—i.e. those folk who probably rarely go to the movies anymore, and why should they, since Masterpiece Theater is still going strong? It’s a beautifully produced, well-cast, richly atmospheric wallow in refined Gothic melodrama that lands smack between Brideshead Revisited and The Others.

Domhnall Gleeson plays Faraday, a young doctor returned to private practice just after WW2 in his home village, where since childhood he’s been obsessed with the magnificent estate of the local gentry—now fallen into disrepair, as the Ayres’ family fortune has shrunk. First called there to address a servant’s minor complaint, he volunteers to treat severely battle-scarred heir Roddy (Will Poulter), but insinuates himself enough with his wallflower sister Caroline (Ruth Wilson) and their mother (Charlotte Rampling) to become a regular guest. But not just misery haunts these dilapidated halls—there’s fear that a third Ayres offspring, long dead, lingers as a malevolent ghost. And the signs of that disturbance are a little too blatant to be comfortably laughed off.

The Little Stranger will likely bore and frustrate those expecting standard horror content, with its leisurely pace, lack of explicit violence, and refusal to definitely commit to any supernatural explanation for various tragedies that occur. Yet it’s satisfying on other levels we get too infrequently at the movies—basically the same ones a big, fat, juicy yet politely old-school literary mystery affords. At the very least, it’s a treat to look at, and not in the usual “sumptuous” Merchant-Ivory way, but in a mode of deteriorated splendor that’s equally attractive…even if it does seem rather unsanitary. At area theaters.

JOHN MCENROE: IN THE REALM OF PERFECTION

The retired enfant terrible of tennis is the subject of Julien Faraut’s documentary, one of the most idiosyncratic and inventive sports docs since the 2006 Zidane: A 21st Century Portrait. Like that film, it’s not a career overview and eschews any talking-head interviews to focus on the subject’s playing style in action. Here, that means intense scrutiny (and occasional manipulation) of archival 16mm match footage, particularly from the French Open in his climactic season of 1984.

Faraut is interested as much in McEnroe’s personality as his technique—both being intimidating, humorless, driven, notoriously temperamental. You might have to be a tennis buff to fully appreciate this eccentric appreciation, but it compels a certain interest no matter how little you know about the sport. Opera Plaza, Shattuck Cinemas. More info here.

RODENTS OF UNUSUAL SIZE

Introduced into the U.S. from Argentina in the 1930s to be bred for fur—a cheaper alternative to mink—the nutria is a large rodent that served that purpose quite well. But once shifting fashion trends tanked the fur industry, there was no longer incentive to hunt nutria, and their populations exploded. Now there’s an estimated twenty-million-plus “big ol’ swamp rats” running around the South, eating everything in sight, destroying wetlands and heightening hurricane damage. (They are also an escalating problem elsewhere, including California.) Never mind that they’re cute—they’re an invasive species wreaking environmental havoc.

This documentary by Bay Areans Quinn Costello, Chris Metzler and Jeff Springer casts a bemused eye on different aspects of the nutria dilemma, from governmental strategies to “Righteous Fur” clothing designers and the critter’s viability as a pet. We even get a glimpse at the annual “Fur Queen Beauty Pageant.” Its episodic progress can feel a bit padded even at 70 slim minutes. But it all goes down easy, in part thanks to an original score by Grammy-winning Cajun band The Lost Bayou Ramblers. The filmmakers will be in person on opening night, Fri/31. Alamo Drafthouse. More info here.

CRIME + PUNISHMENT

One of those “officially denied yet universally known” truths is that police have quotas—that they issue a certain amount of tickets and make a certain number of arrests because they’re under administrative pressure to reach a particular “activity” number each month. This can lead to race and age profiling, or worse: Lives derailed or ruined outright due to allegations that prove baseless, and were arguably initiated solely so a cop could “hit quota.”

In Stephen Maing’s potent documentary, a dozen NYPD officers disgusted by the pressure to file 25 summonses a month go public exposing policies that have the effect of ““killing communities of color…by lockin’ em up for no reason.” They claim that poor youths age 14 to 21 are primarily targeted, often on completely fabricated charges. Most of the latter are eventually dismissed, but damage is done nonetheless—one kid here spends months at Riker’s on an attempted murder charge despite numerous witnesses backing up his story, and the arresting cop having a history of false arrests.

The “NYPD Twelve” are predictably punished internally for their “betrayal,” even as officials continue to deny these quotas exist at all. This is an important document for our era, when relations between law enforcement and minority communities continue to deteriorate, and police training seems to be gravitating away from defusing conflicts to escalating them with excessive force. Roxie. More info here.

GABRIEL AND THE MOUNTAIN

At the beginning of Fellipe Gamarano Barbosa’s film, two tribal men in Malawi stumble upon a white man’s corpse at the foot of Mount Mulanje. Rewinding to six months earlier, we meet the living Gabriel Buchmann (Joao Pedro Zappa)—a Brazilian student touring Africa way off the tourist grid. He seems one of those marvelously open, unself-conscious people who can make himself feel at home and welcomed anywhere.

When he begins demonstrating erratic behavior—sometimes sulky, volatile, unreasonable—on a Mt. Kilimanjaro climb, we chalk it up to the effects of high altitude. But after his girlfriend Cristina (Caroline Abras) arrives for a visit, it becomes clear Gabriel isn’t entirely the free spirit he’d appeared. In fact, as admirably avid in pursuit of new experiences as he is, it grows obvious that he can’t accept the validity of any perspective but his own. It’s that stubborn tunnel vision which proves his undoing. No lack of wiser, more experienced persons advise him against the decisions that ultimately seal his doom, and he ignores them all.

Apart from the two professional-actor leads, Mountain has the novelty of everyone the real Gabriel met on his final trip playing themselves, adding considerably to the film’s authenticity. Still, this international-edition parallel to Into the Wild actually gets less compelling as it goes on, largely because we care less about our protagonist.

There is something less than tragic (or even sympathetic) about the person who knowingly shrugs off all precautions and puts themselves in a dangerous situation—just for fun, not even out of necessity—thinking themselves invincible, then discovering they’re not. The film 127 Hours soft-pedaled the extent to which its real-life “hero” was a reckless thrill junkie who’d frequently endangered himself (and sometimes others), as his own book made inadvertently plain. Gabriel and the Mountain is a warts-and-all equivalent, appealing in its scenic attractions but cautionary in its psychological ones. Opera Plaza, Shattuck Cinemas. More info here.

BETWEEN POLITICS AND POETRY: MAKHMALBAF FILM HOUSE

Mohsen Makhmalbaf was (and remains) a major figure in the Iranian New Wave, with films like 1996’s Gabbeh and 2001’s Kandahar being among the nation’s most widely disseminated around the world. (And in classic modern Iranian style, at least half a dozen of his twenty-plus features have been banned from home-turf viewing by the government, even as he continues to work.)

This Pacific Film Archive retrospective celebrates not just his personal output, but that of family members (including daughter Samira, who famously directed The Apple at age 17) and others who’ve benefitted from his encouragement and backing of young filmmaking talents. The films that resulted often reflected Makhmalbaf’s own established penchant for mixing elements of documentary with fictional narratives, and exploring issues of social injustice (particularly women’s limited freedom) not just in Iran, but Afghanistan, Kurdistan, Tajikistan, and other struggling parts of the modern Islamic world. The films selected will be shown mostly in imported 35mm prints. Sat/1-Sat/Oct. 20, PFA. More info here.