San Francisco’s artists, small blue-collar businesses, and community-serving nonprofits are being forced out of the city by soaring rents; outright evictions; and, in many cases, the elimination of their workspaces by high-end development.

Prop. X, the final San Francisco measure on the November ballot, addresses the last of these threats. It would require developers of projects in parts of the Mission and SoMa to partly or fully replace space for neighborhood arts and small blue-collar businesses—in local plannerese, Production, Distribution and Repair or PDR—and for nonprofit community services such as child care and job training that the projects would demolish or convert to other uses.

Prop. X’s opponents say ballot-box zoning is a bad idea. “This is exactly the wrong way to make complicated land use decisions,” SPUR Executive Director Gabriel Metcalf told the Chronicle. “The reason we have a Planning Department and Planning Commission is to be thoughtful and careful about our land use decisions, and it makes no sense to short-circuit that with simplistic ballot measures” that are “hastily conceived, with no analysis or data.”

Here’s what’s simplistic: The Opponent’s Argument Against Proposition X that appears in the official Voter Information and Sample Ballot, co-signed by Metcalf, complains that the measure “includes no rules telling building owners how much they can charge in rent.” Doesn’t SPUR’s executive director know that commercial rent control is illegal?

Trouble is, PDR uses can’t pay commercial (office or residential) market-rate rents.

Prop. X begins to address that problem. If the required PDR replacement space is rented, leased, or sold at 50% below market rate and deed-restricted for 55 or more years, the replacement requirements may be reduced by 25%.

Prop. X supporters concede that asking voters to make zoning changes is generally a bad idea—the operative word being “generally.” Speaking at X’s October 6 kickoff, Supervisor Jane Kim, the measure’s primary sponsor at the Board of Supervisors, averred, “I don’t believe in ballot-box zoning, except when the city doesn’t act. Then the city has to hear from the voters.”

By act, Kim meant taking steps to protect space for artists; blue-collar workers and businesses; and child-care, job-training, and other community serving non-profits, whose numbers have been decimated by the rash of big, high-end developments in the Mission and SoMa since the last boom began, and that stand to be further slashed by similar projects that are advancing through the Planning Department pipeline.

Help us save local journalism!

Every tax-deductible donation helps us grow to cover the issues that mean the most to our community. Become a 48 Hills Hero and support the only daily progressive news source in the Bay Area.

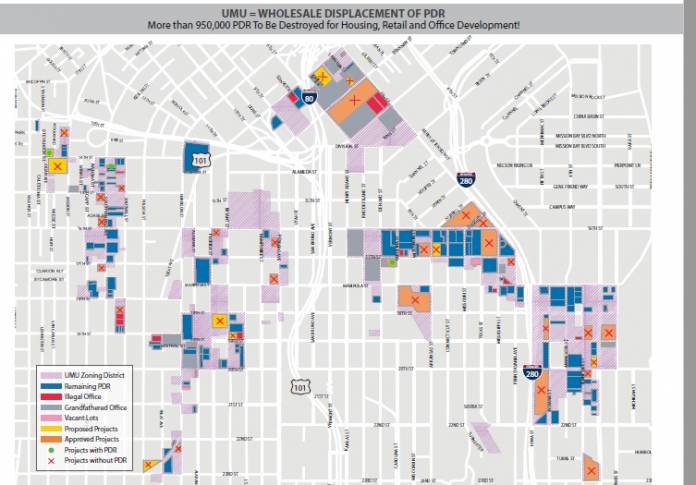

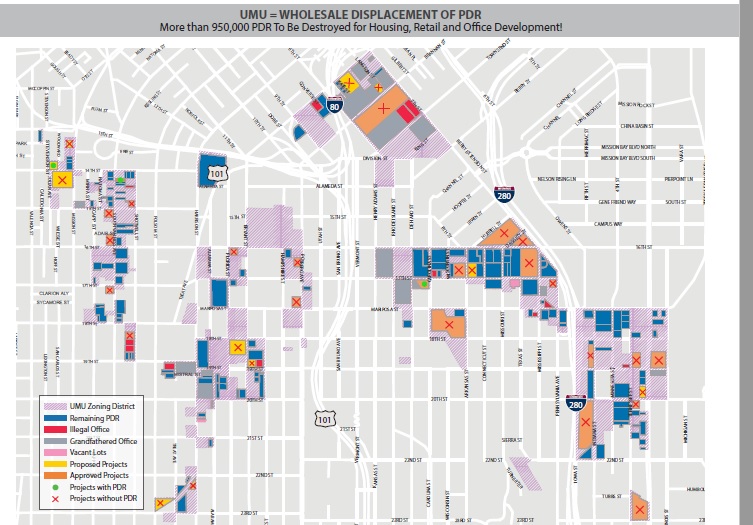

The numbers are stark. The Eastern Neighborhoods Monitoring Reports, transmitted to the Planning Commission by the Planning Department in September, show that between 2011 and 2015, the Mission, Central Waterfront, East SoMa, Western SoMa and Showplace Square/Potrero Hill neighborhoods lost 970,000 square feet of PDR space.

Still threatened in the pipeline are about 614,000 square feet of PDR in projects that are under review but have not received entitlements from the Planning Department. If those projects are approved, “the Eastern Neighborhoods will see another 1.39 million square feet of PDR space converted to other uses.”

The research behind Prop. X

Contrary to opponents’ claims that Prop. X was “hastily conceived, with no analysis or data,” when the Board of Supervisors voted 7-4 in August to place Prop. X on the ballot, Kim’s office had been working on such a measure with the neighborhood arts community for a year and a half.

In September 2015 the Arts Commission published the findings of its six-week survey of artists’ space needs and displacement. As KQED reported, more than seventy percent of the nearly 700 respondents said that they had been or were being displaced from their workplace, home, or both. The other thirty percent were worried about being forced out. The major sources of displacement were building conversions, rent increases, and new owners, including new owners moving in.

The Arts Commission’s findings were confirmed and supplemented by studies done by the non-profit housing organization TODCO, particularly an August, 2014 building-by-building survey of potential illegal office use in the Service/Arts/Light Industry (SALI) and Service/Light Industry (SLI) zoning districts in Central SoMa (update out next week) and a Summer 2015 survey of commercial and “community arts” practitioners in SoMa between 2nd and 11th streets.

In the spring of 2015, TODCO CEO John Elberling, the signatory to the Rebuttal to the Opponent’s Argument against Prop. X, went to Kim and said they had to do something to stop the rampant displacement. Working with artists and their supporters, they formulated Prop. X, which also incorporates suggestions from SFMade Executive Director Kate Sofis.

PDR displacement is not “on schedule”

Everyone agrees that neighborhood arts, light industry, and community-serving non-profits are being displaced by commercial gentrification.

Some people, however, question the seriousness of the displacement. In a public debate with Kim at the Swedish-American Hall on October 17, Housing Action Coalition Executive Director Tim Colen, another signatory to the Opponent’s Argument, pronounced PDR “worthy”—he compared it to motherhood and apple pie—but said that its displacement was “right on schedule.”

Colen was referring to the forecasts in the 2008 Eastern Neighborhoods Plan, whose re-zoning opened much of the city’s industrial lands to housing and small offices. One of the plan’s express goals was to stabilize the city’s PDR. The old Manufacturing zones had allowed nearly any use, including housing (with a Conditional Use permit). That promiscuous approach to land use was eroding space dedicated to industry.

According to the Eastern Neighborhoods Plan Environmental Impact Report, under the new zoning

land designated for PD use…would be available almost exclusively to PDR uses, with housing not permitted, and only relatively small non-PDR uses (such as office or retail space accessory to PDR use) would be permitted[,]

thereby

“provid[ing] clearer definition between land uses in PDR zones where such definition does not now exist. In addition, the proposed project would include UMU [Urban-Mixed Use] districts where new PDR pace would be required to be built as part of new residential projects.

But by allowing housing as an explicitly permitted use in formerly industrial areas—increasing the supply of housing, particularly affordable housing, was the other major goal—the Eastern Neighborhoods Plan was also expected to eliminate between 2.1 and 4.9 million square feet of PDR space by 2025.

The 2016 Monitoring Report does venture that “the pace of development since the adoption of the Area Plans has been consistent with the protections of put forward in the Eastern Neighborhoods Environmental Impact Report (EN EIR)” (Executive Summary, p. 2).

But the Report immediately backpedals, noting that

the Area Plans were enacted in 2008, right as the U.S. economy went into a sharp downturn caused in large part by a collapse of the national housing market. New housing and commercial construction largely dried up during the first years of the Plans and rebounded quite strongly since 2012. As a result much of the development activity that has taken place in the Plan Areas has been concentrated over the last few years rather than following a smooth line since 2009.

(How’s that for understatement?)

Nowhere in the Monitoring Report will you find a year-by-year schedule of new development or PDR decline. Nor will you find the slightest sense of urgency regarding the state of PDR in the Eastern Neighborhoods.

In any case, the 2008 plan could not possibly have anticipated either the current, historic boom or another surprising phenomenon, the rise of urban manufacturing and the maker movement in San Francisco. Today there’s newfound demand for, and a serious dearth of, production space in the city.

Which brings us back to the core issue, which Kim spelled out: the city’s failure to act in behalf of PDR.

The Planning Department sabotages PDR: The Eastern Neighborhoods Plan

In truth, under the auspices of the Planning Department and the Planning Commission, those agencies commended to us by SPUR’s Metcalf, the city has repeatedly acted. Unfortunately, with few exceptions, and those very recent, those actions have undermined the land use protections afforded to San Francisco’s artists and small, blue-collar businesses.

48 hills has reported instances of this sabotage:

- the draft Central SoMa Plan’s proposed destruction of nearly 2,000 PDR jobs

- the Planning Department’s facilitation of the illegal conversion of PDR into office space

- the planners’ heavy discounting of development impact fees for converting PDR into office space, a practice that not only encouraged the decline of the city’s PDR but also deprived Muni and affordable housing of millions of dollars. (Thanks to land use attorney Sue Hestor, these giveaways to the real estate industry finally stopped.)

To this inventory, we now add two more items. The first dates back to the formulation of the Eastern Neighborhoods Plan itself: planning staff’s quiet removal of the plan’s requirement that new PDR space be created in non-PDR development in the Urban Mixed Use (UMU) zone. That requirement was repeatedly stipulated by the Plan’s EIR.

The EIR even specified a ratio of new PDR to new non-PDR: in the draft Showplace Square/Potrero Hill Plan, “the UMU designation would require one square foot of PDR space for every four square feet of non-PDR development.” (Project Description, p. 13, fn 17) That draft also included an Arts District in which five square feet of “arts-PDR” use would be required for every square foot of new residential construction, except student housing.

Brought down to earth, this requirement would have affected two massive, recently approved developments that destroy existing PDR—one at 2000-2070 Bryant, a.k.a. the “Beast on Bryant,” the other at 901 16th St./1200 17th St. Both are on land zoned UMU. Another big project in the UMU, still under review, the San Francisco Armory at 14th and Mission, would convert more than 100,000 sf of PDR to office uses.

The Eastern Neighborhoods Plan EIR was published on June 30, 2007. It was certified by the Planning Commission on August 7, 2008. Some time in 2007, planning staff eliminated the requirement for new PDR in non-PDR development in UMU, but left it in the EIR.

I’ve found only one reference to this removal. Staff presented the Eastern Neighborhoods Plan at a special nighttime meeting of the Planning Commission on September 6, 2007. Under “Purpose,” the PowerPoint slide dedicated to UMU stated: “Transition formerly industrial zones into mixed use/mixed income districts, while preserving PDR uses.” Under “Other”: “PDR space no longer required as part of residential projects.” The staffer who narrated this slide, Ken Rich, somehow neglected to read the text about the elimination of the new PDR requirement.

Much more important, the document certifying the EN EIR says nothing about the removal. The only mention of UMU that I’ve located there is this muddled statement:

[I]n recognition of providing for a diversity of future employment types, the Preferred Project also proposes two special use districts and controls (e.g., ‘UMU,’ ‘Hybrid Office/PDR District,’ Small Enterprise Workspace controls, etc) where office growth would be permitted as well as about 357 acres of land zoned for a mixed [sic] of uses where growth of other types of business activity in the commercial, retail and personal/business service sectors could also be accommodated within the Eastern Neighborhoods, in close proximity to housing.” (p. 21)

The removal of the requirement for new PDR in UMU seems like a significant change to the project, i.e., the EN Plan. Consider just Showplace Square/Potrero Hill, which lost 207,645 sf of PDR space between 2011 and 2015. The Monitoring Report for that area found that the conversion of PDR into other uses “occurred primarily within UMU zoning.”(p. 16)

Under certain conditions, including a situation in which the public has not been given adequate opportunity to comment on a significant change in a project, the California Environmental Quality Act requires an EIR to be re-opened and re-circulated.

It’s eight years too late to mount a legal challenge to the EN EIR. But it’s not too late to ask: who removed the new PDR requirement and under what authority? And why wasn’t that removal flagged in the document certifying the EN EIR?

On October 17 I put those questions to SF city planner Steve Wertheim. He went to work on the EN Plan in May 2006. On March 23, 2016, he sent this email to colleagues in the Planning Department who’d queried him about the removal of the PDR in UMU requirement:

I killed PDR in the UMU, thank you very much. 2007. There definitely wasn’t enough compatible PDR to smear across all of the UMU (and we’ll be finding out if there’s enough to smear across all of the Mission).

Wertheim’s message implied that the PDR he “killed” already existed. But the requirement set forth in the EN EIR required the creation of new PDR in the UMU. I asked him to explain what, then, he meant or thought he was doing in 2007. (I also queried Rich, who however, turned out to be on vacation until October 24.)

In an emailed reply, Wertheim said that his March email was “an offhand comment to old colleagues as part of a longer conversation.” He didn’t explain his apparent reference to existing as opposed to new PDR. He also detailed Planning staff’s considerations for removing the PDR requirement, noting that “about ten people were working on the project, often working as a team, so that it’s not possible to identify the genesis of all of the ideas.” “Any of these ideas,” he added,

were vetted by the Project Manager (Ken Rich) and ultimately, as part of an overall balanced package, the Planning Director (Dean Macris, and then John Rahaim [who arrived in January, 2008], and eventually the Planning Commission and the Board of Supervisors.

Whatever the planners’ rationales for excising the PDR requirement, that removal should have been highlighted to the public. To my knowledge, it was not.

As for Wertheim’s comment: no doubt it was, as he said, offhand. But casual remarks, especially ones made in emails, are often more revealing than studied pronouncements, especially ones made in public (which is why, as a former litigator once told me, lawyers go after emails).

At meetings of the Planning Commission, staffers always pay homage to the wonderfulness of PDR. That Wertheim felt comfortable expressing disdain for Production, Distribution, and Repair, testifies to his agency’s true attitude, particularly with respect to PDR’s more modest forms.

Planning Department sabotages PDR: The Central SoMa Plan

That contempt comes across in the second addition to the list of Planning’s offensives against neighborhood arts and small, blue-collar enterprise: the treatment of PDR in the revised Central SoMa Plan. (Not incidentally, that project is being overseen by Steve Wertheim.) The version that I critiqued in 48 hills in early 2014 was the first draft. In August 2016 the Planning Department released a second edition, entitled the Central SoMa Plan and Implementation Strategy.

Among the changes in the new version were amendments purportedly designed to address community objections to the first edition’s of PDR.

TODCO reviewed the new proposal and found that:

- The Arts/PDR SALI Protection Zone of the community-sponsored 2013 West SoMa Plan is totally wiped out.

- Nearly all of Central SoMa will be re-zoned as MUO (Mixed-Use/Office) where anything goes—offices, housing hotels—at high market rate prices.

- There is no requirement at all for future housing development to replace the Arts/PDR spaces it destroys, so developers can target Arts/PDR locations everywhere.

- The requirement for office space to replace the Arts/PDR spaces it destroys applies only to larger projects (>50K sf), so smaller “49er” office buildings can target Arts/PDR locations everywhere.

- There is no requirement or incentive for the future replacement of Arts/PDR spaces to be actually affordable for anything except high-end PDR businesses

- There are no relocation requirements, no cash assistance, no right-to-return for displaced Art/PDR businesses and groups.

The conclusion:

Overall, it is evident that the Planning Department simply does not care about protecting EXISTING Arts groups and PDR small businesses in SoMa (and the Mission, too)—they are expendable. New development always gets top priority. (Handout at TODCO public meeting, August 31, 2016)

In light of the Planning Department’s record, expecting the planners to take a “thoughtful and careful” approach to PDR, as Metcalf advises, is ludicrous.

Consider Prop. X an effort to remedy some of the Planning Department’s damage. Its passage just might usher in a new era of democratically accountable land use planning in San Francisco.

Thanks Zelda for leaving us on a hopeful note. If Proposition X passes along with the rest of the progressive slate, we may look forward to a friendlier future in which the public participates in crucial decisions plans are fully etched in stone by City Hall and developers beating the profit motive drums. There must be room for growth that is not dictated by greed and the profit motive. The best of San Francisco cannot be sold because it is free and must be protected.

An attentive walk around the Mission/Potrero area will reveal a number of PDR conversions to high-tech/disruption-capitalism/sharing-economy/bubble-2.0 office space.

PDR spaces often have loading zones that cross the sidewalk and require a driveway to access. A number of the new office spaces have gotten rid of the drive-in loading areas because they don’t produce, distribute or repair anything. Those same business, however, continue to post no parking signs in along the former driveways so they can have permanent office-specific free parking right outside their door.

Here are two examples at Mariposa and Alabama:

https://www.google.com/maps/@37.7634464,-122.412248,3a,75y,269.91h,68.36t/data=!3m6!1e1!3m4!1sRY0ADp7tH-WAFmcTpAir7g!2e0!7i13312!8i6656

https://www.google.com/maps/place/2825+mariposa+street+san+francisco/@37.7629405,-122.4118274,3a,75y,166.64h,90t/data=!3m6!1e1!3m4!1sbNtgUtaw2GLg9oMdmGAYFw!2e0!7i13312!8i6656!4m2!3m1!1s0x0:0xe72e357413c47216!6m1!1e1