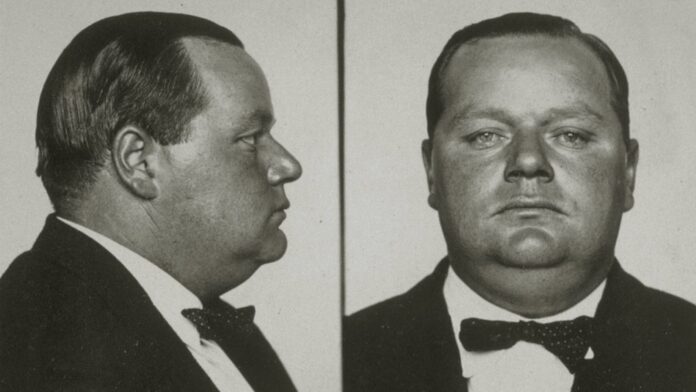

Last weekend marked the centenary of Hollywood’s most notorious scandal during the silent era, even though the (disputed) events concerned took place right here in SF. At the St. Francis Hotel, Roscoe “Fatty” Arbuckle—then second in popularity only to Charlie Chaplin among screen comedians—and friends rented three rooms to get away from LA for the Labor Day weekend. Among those who showed up to party were two uninvited women, Virginia Rappe and her new acquaintance Maude Delmont. 25-year-old Rappe was an actress engaged to established film producer/director Henry Lehrman. At some point she became ill from what was diagnosed as a ruptured appendix, dying in the hospital four days later.

Delmont accused Arbuckle of causing Rappe’s condition via sexual assault, though he and other witnesses claimed he was never alone with her. It eventually emerged that Rappe had cystitis, possibly caused by then-illegal abortions, and that alcohol consumption at the party likely aggravated her already-fragile health. Also, Delmont had a rap sheet for prior arrests involving blackmail, extortion, prostitution and procuring. Nonetheless, the tabloid press seized on the horror of America’s beloved clown Fatty being some sort of boozed-up sex monster. (The drinking was bad enough, given that Prohibition was already in effect.)

After two mistrials, a third jury not only acquitted Arbuckle, but issued a formal public apology for the “great injustice [that] has been done him…for there was not the slightest proof adduced to connect him in any way with the commission of a crime.” Still, the trials bankrupted him, and the negative publicity basically ended his acting career. He continued working with some success under pseudonyms as a writer and director, thanks to loyal friends in the industry. But to many, he seemed a broken man—few were surprised when he died of a heart attack in 1933, aged just 46.

So much of the silent era’s films are now lost, having been deemed of no lasting worth once “talkies” arrived, and preservation for art’s (or television’s) sake not yet thought of. Those Arbuckle films that have survived, however, are now in the public domain and easy to find online. They include still-funny ones like 1918’s Good Night, Nurse!, where he gave an early career leg-up to collaborator Buster Keaton.

Much less footage exists of Rappe, who herself became posthumously villainized as a mere bit player and “good time girl” once the charges against Arbuckle were generally accepted as false. But while it’s unclear just how many real roles she had in long-MIA films, she can be prominently seen in the curio The Isle of Love, a vehicle for famed cross-dressing actor Julian Eltinge. It was shot in 1918 as Over the Rhine, then shelved, because the end of World War I that year rendered its plot irrelevant. But four years later, it was released in drastically re-edited form to cash in on both Rappe’s death and fellow player Rudolph Valentino’s subsequent fame.

They have several scenes together, Rudy atypically restrained in waxed mustache and monocle, she animated and elegant, a dark beauty in the mode of such contemporary ingenues as Barbara La Marr and Dolores del Rio. The mass of jokey intertitles betray the repackaged film’s patchwork nature, with its awkward mix of patriotism and farce, bathing beauties and fictitious foreign political unrest. (There’s also some surprising near nudity in an Isadora Duncan-esque cafe dance performance.) But those two doomed stars, one already deceased by the time Isle got released, seem to exist in their own more dignified, more glamorous universe.

The farther you go back in movie history, the more shocking it is how young many professionals in that medium were when they died—suggesting people did indeed live (and party) harder back then, admittedly without the benefit of today’s advances in medical science. Now, by contrast, we have actors like Ellen Burstyn or Clint Eastwood still at it in their nineties, as well as no lack of directors who are doing some of their best work at age well past the point of mandatory retirement in some professions. That definitely includes Paul Schrader, whose new The Card Counter opens this Friday. Like his last feature five years prior, First Reformed, it’s an admirable distillation of his proven strengths as a screenplay writer of questioning moral seriousness, and a director of spare, elegant precision.

Shot during the pandemic (which shut down production for a while), it has Oscar Isaac as Bill, a prison parolee who learned some tricks in stir. Now he makes a deliberately modest living at under-radar casinos around the country, cheating to win stakes small enough for management to ignore, the rootlessness and repetition suiting a socially detached, OCD-accommodating personality. Nonetheless, his skills attract the attention of one La Linda (Tiffany Haddish). She oversees a “stable” of such sharpsters, bankrolling them toward higher, and riskier, windfalls. Bill agrees to briefly play her way because he’s acquired a sort of mascot, Cirk (Tye Sheridan), whom he wants to help out—largely because the young man’s life has been stunted by matters connected to what originally landed Bill in jail, and which still haunt his sleep-deprived nights.

The Card Counter is meticulous about the way casinos and their games work, lending them the same luxurious, fetishistic visual treatment accorded the tools of Richard Gere’s trade in American Gigolo. (Indeed, Schrader often seems to be directly referencing that first directorial hit of his 40 years ago, particularly at this film’s close.) But it’s hardly an Ocean’s 11-style caper of hijinks against the house. Instead, the film uses gambling as a device with which to circle, then dive into larger issues—not least American imperialism, and corruption within our governmental and military ranks. Suffice it to say that there are flashback scenes in a Guantanamo-type hellhole, where Willem Dafoe plays a figure not unlike, say, Blackwater’s Erik Prince. All this messaging might come off as heavy-handed in a different narrative context. But Schrader knows exactly how to play these cards, rigorously underplaying even the eventual shocks of horrified discovery.

As a thriller, not all of Counter’s plot mechanics hold up under scrutiny afterward. But then, the film is really aiming for something else, anyway—making crises of conscience more vivid to us than the violence it seldom does more than hint at. With Isaac perfectly cast as its still yet tormented center, this is a movie whose Zen quietude and Gigolo-esque pastel aesthetics just mask the near impossibility of inner peace in a world of war.

In conjunction with The Card Counter’s release to theaters nationwide, the Roxie is reviving Schrader’s directorial debut from 1978—two years after he’d made everyone take notice with the screenplay for frequent future collaborator Martin Scorsese’s Taxi Driver. Blue Collar is in a similar vein of working-class malaise, if not driven so far into derangement. Richard Pryor, Harvey Keitel, and Yaphet Kotto play automotive factory workers treated poorly by their bosses, jerked around by their own union, slowly sinking into debt amidst the era’s “stagflation”—hard-won wages failing to keep pace as costs of living rise. They get the idea of committing a robbery that would afford sweet payback. But it all goes wrong, the bitterly ironic consequences underlining that people like these can’t win by kicking against the pricks; they will get crushed.

Blue Collar wasn’t a major commercial success, its downbeat content not being what people wanted from a Pryor film, while the cynical take on union corruption meant no inspirational uplift a la the same year’s pro-union hit Norma Rae. (The movie had to shoot primarily in Kalamazoo, because no major auto manufacturers in Detroit would condone such a negative depiction.) It was also apparently a nightmare to make, with the three leads at each others’ throats, and Pryor reportedly drawing a gun on Schrader during one drug-addled rage. It wasn’t quite a great film then, and it isn’t now. But there’s an authenticity of observation that still stands out, even amidst the famously “gritty” 1970s American film landscape, plus an integrity to the performances (no matter how much those stars hated each other) and filmmaking that’s likewise aged very well. The Roxie is playing a 35mm studio vault print Sun/12, more info here.

Also currently playing the Roxie is 499 by Oakland-based director Rodrigo Reyes, making his narrative feature debut. A Spanish conquistador (Eduardo San Juan Brena) who’s just finished pillaging the New World as part of Cortez’ crew finds his loot-filled ship wrecked en route back home. He alone survives to be washed back ashore on the beach of Veracruz… 500 years later, by some “secret miracle.” This “castaway in the future” wanders the same route he had before, now modern and alien, everywhere finding evidence of the ongoing dehumanization his original conquest seeded.

Part documentary, 499 is largely occupied with input from real people who’ve suffered grave injustices echoing those visited upon Indios and Aztecs centuries before: The murderous abductions of whistle-blowing journalists and activists; volunteers who search for hidden mass graves of the disappeared; families decimated by drug cartel violence; others forced by such threats to flee north, seeking asylum legal or otherwise in the US. Corruption seems bottomless, even extending to police “mishandling” evidence so that neighbors caught red-handed in the brutal murder of a 12-year-old girl end up going free. Weaving these testimonies into a poetical whole, with gorgeous landscape photography and moments of Jodorowskyesque phantasmagoria, 499 is a unique filmic essay with great depth and beauty.

Streaming on Roxie Virtual Cinema is another, more purely nonfictive inquiry: Yael Bridge’s The Big Scary “S” Word (info here). This documentary is a terrifically cogent look at why socialism is in fact “as American as apple pie”—and why so many powerful political forces work so very, very hard to paint the whole concept instead as a menace to our society.

Incorporating a colorful array of animation, archival clips, interviews (with Naomi Klein, Cornel West etc.) and so forth, it’s a great argument against the notion that unfettered free market capitalism alone offers “freedom” to any but the richest percentile. Who, naturally, want to convince us socialist principles equal some kind of “Red terror,” lest their ever-increasing profits be reined in once again to actually benefit a labor force subject to ever-greater economic inequality. This is potentially dry material handled very entertainingly, so much so that the Trumpite lurking in your family might find themselves agreeing with much that’s said before they remember to dismiss it all on “I know what I like, and it isn’t socialism, even if I don’t really know what that word means!!” principle.