SF wants to let speculators and developers pay far less than they owe for providing Muni service — meaning the rest of us have to pick up the tab

By Tim Redmond

SEPTEMBER 8, 2015 – One of the simplest doctrines in modern urban planning is also one of the most powerful: Growth should pay for growth.

Seems simple: You want to put up a new office tower or condo complex in San Francisco? That’s going to mean the city needs to buy more Muni buses and hire more drivers to move your new workers or residents around, and more firefighters and cops to protect your property, and more public works people to maintain the roads that suddenly have more cars on them, and more water and sewer infrastructure to handle what you take in and put out … and the list goes on.

Since developers in this city typically make gobs of money for themselves and their investors, it makes sense that they should pay for the costs or serving their projects. Otherwise, the rest of us have to pay – and that’s clearly unfair.

How do you know how much new projects cost the city, and how much they pay in taxes, and what the net impact is? Well, there are people who study this sort of thing for a living, and while I can accept the complaints of critics that not every study on urban economics is accurate and paid consultants have a tendency to deliver what their clients want, there’s a certain consistency in many, many years of analysis that says developers in San Francisco pay far less than their fair share.

Back in the early 1980s, transit and environmental advocates argued that, at the very least, office developers ought to pay for impacts on Muni. The city did a study, and it showed that the impact ran to almost $10 a square foot – that is, every square foot of new office space cost the city almost $10 in new Muni expenses. Then-Mayor Dianne Feinstein wouldn’t go for that; she finally settled on a $5-a-square foot charge.

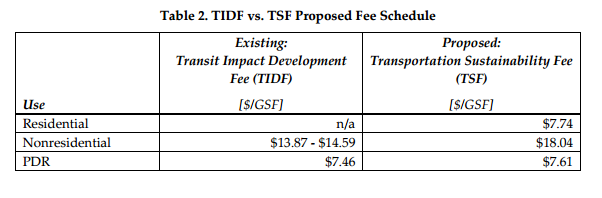

The fee has gone up a little over the years – most projects now pay between $13.85 and $14.50 a year — but has never been enough to cover the actual costs. And market-rate housing developers have never paid a penny.

Help us save local journalism!

Every tax-deductible donation helps us grow to cover the issues that mean the most to our community. Become a 48 Hills Hero and support the only daily progressive news source in the Bay Area.

So the SF Planning Commission will hear a proposal Thursday/13 that would change the name of the fee, simplify its structure, and apply it to market-rate housing projects.

The proposal comes out of the Mayor’s Office, and is sponsored by Sups. Scott Wiener, London Breed, and Julie Christensen.

As is usually the case with these things, you have to read the fine print to get the point. Which goes like this: The proposed fee is way, way too low to even begin to offset the costs of new development.

Before the city can charge a fee, it has to do a “nexus” study to look at the actual cost of providing the service. If the fee is higher than the cost, that becomes a “tax,” which under state law requires a vote of the people.

So the nexus study tells us exactly how much a service (providing Muni to new development) really costs. That’s called the “maximum justified” fee. If the fee is above that, it’s illegal.

So the economists look at the costs of Muni service and other transportation needs, spread out over about 30 years, and analyze how many workers will fill the new offices or residents will live in the new condos, and how much pressure that will put on transportation, and how much it will cost to meet the increased demand. It’s actually not that complicated: We know how much bus service costs per rider, and how much wear and tear on the streets costs, and how much parking and other improvements costs. These studies have been done many times over the years, in many place.

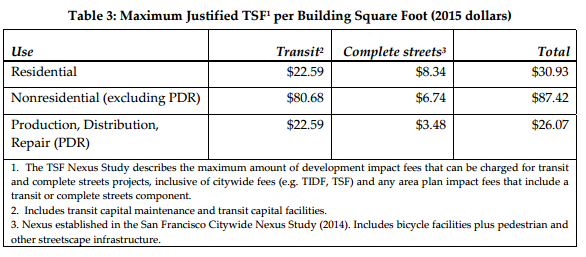

In this case, the nexus study, by Urban Economics, found that the real cost of meeting all of the city’s transportation and street needs is as high as $87 a square foot for office buildings.

The proposed fee is $18.04.

For residential buildings, the real cost of Muni and other transportation services could reach $30.93.

Those developers would pay $7.74.

Now: Maybe the nexus study is high, with the consultants using every trick in the book to give the city as much leverage as it can. Maybe it’s off by, oh, 50 percent. (I don’t think it is; the numbers seem pretty solid to me. But I lack a Ph.D, so let’s give the critics lots of leeway.)

The taxpayers are still getting screwed.

The total annual fee is projected at $14 million, or $420 million over 30 years. Sounds like a lot of money. Except that if we charged even half of what we should, that number would be in the billions.

Why so low? Well, the City Planning Department report explains it this way:

The economic feasibility study found that the current market could support $7.74/GSF for residential uses and $18.04/GSF for non‐residential uses citywide, or roughly 125% of the levels proposed in 2012 (accounting for cost inflation). These fees would amount to an increase of roughly 1 to 2% of construction costs for residential developments, and less than 1% of construction costs for nonresidential projects, depending on project and construction type.

The study found that this would not have a major impact on overall project feasibility or resulting housing costs in neighborhoods where most new development is occurring.

The study also found that raising the TSF above these proposed amounts could inhibit development feasibility in some areas of the city and for some project types. New development in certain neighborhoods in the City – such as the western neighborhoods and outer Mission – have lower than average price levels and rents and may not be financially feasible given the current high cost of construction relative to potential revenues. While the TSF itself will not cause these developments to be infeasible, it may further distance these areas from development feasibility.

Read that again, carefully; it’s a pretty amazing statement.

A fee that actually covers the costs that developers are throwing on the city “could inhibit development feasibility in some areas of the city and for some project types.” Not apparently, for the luxury condos and Class A office space that’s being jammed into every available lot downtown; just for smaller projects on the west side of town that aren’t getting built anyway.

So the city is taking into account what the developers can afford to pay – forgetting that most development in the most attractive areas right now is returning at least – at least – 15 to 20 percent for investors, and in many cases much, much more.

But let’s step away from that for a second. Someone has to pay to keep Muni up to date. If developers bring tens of thousands of new residents and workers to the city and don’t pay the full cost, then either (a) Muni gets more crowded and slower (sound familiar?) or (b) the rest of us — the collective homeowners and renters, office workers and house cleaners, hotel bellhops, bartenders, hospital orderlies, teachers, nurses, cops, nonprofit service providers, and the rest of the collective San Francisco Muni users, drivers, and taxpayers — have to cough up more for bus fares, parking meters, sales taxes, and bond payments to keep the essential services alive.

Charging a fee that keeps the rest of us poor suckers from underwriting international speculative real-estate investors and giant developers might make some buildings less “feasible?”

Well guess what? From the city’s point of view, then, those projects shouldn’t be feasible.

Why is it feasible to let a developer make a profit on the back of the ordinary taxpayers, Muni riders, and parking-meter users?

Shouldn’t growth pay for growth – at the full rate?

After the Planning Commission hears it (and staff recommends approval, so with this commission it will likely go through), this latest giveaway to developers and speculators will go to the Board of Supervisors.

Member of the faculty union at City College have voted by a 93 percent margin to begin funding a Strike Hardship Fund, the first step toward a strike that would be a disaster for City College.

The vote was overwhelming for a very good reason: The salary offer that management has put forward is far, far from what the faculty is seeking. AFT Local 2121 wants a 16 percent cost-of-living increase over the life of the contract to bring “full-time faculty salaries above the median of Bay Ten community colleges and to restore losses to inflation (CPI) to all unit members.”

Let’s recall that in 2007, the union members took pay cuts and salary freezes, and haven’t had a raise since then.

Management’s offer is a 1.1 percent raise about 2007 salary levels – for full-time faculty only. Part-timers would get nothing.

I can tell you from talking to union members: That’s not going to work.

The union has also asked that enrollment be a part of the deal – the teachers want to help bring back the students who have been lost through the accreditation ordeal. Management says that’s none of the faculty’s business.

So this will be a test for the newly empowered Board of Trustees. City College is still struggling to get out of the deep hole that the ACCJC dug. A faculty strike is the last thing the board should be willing to accept.

Typically, governing boards leave these negotiations to hired management until the last minute. But this situation isn’t typical.

By the way: When the ACCJC started its crackdown, there were political leaders all over the city, starting with Mayor Ed Lee, who tried to blame City College and said that the accreditors had raised valid points that needed to be addressed.

But now, as my friend and former colleague Joe Fitzgerald Rodriguez pointed out in this exceptional column, it’s clear that those people were wrong. The problem was never City College; it was the ACCJC. And now that the state has agreed, and it’s increasingly likely that Barbara Beno and her colleagues will be out of business pretty soon, we need to look back at the people who were wrong about this and call them out.

Meanwhile, there will be a remarkable community hearing Wednesday/9 to discuss faculty working conditions and student learning conditions at City College, SF State, and the SF Art Institute.

Jobs with Justice is hosting the Workers’ Rights Board hearing on the future of higher education in San Francisco, with a panel of city and state educational leaders hearing testimony and issuing recommendations.

The event’s at 6pm at St John the Evangelist Church, 1661 15th St.