UPDATED, see the end.

The 1974 kidnapping of Patricia “Patty” Hearst, granddaughter of the founder of the Hearst media empire, was a dramatic chapter in San Francisco history, and a curious collection of books have tried to make sense of what happened.

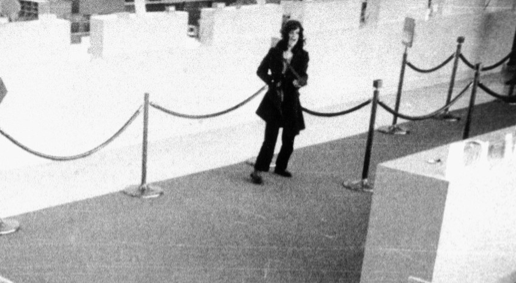

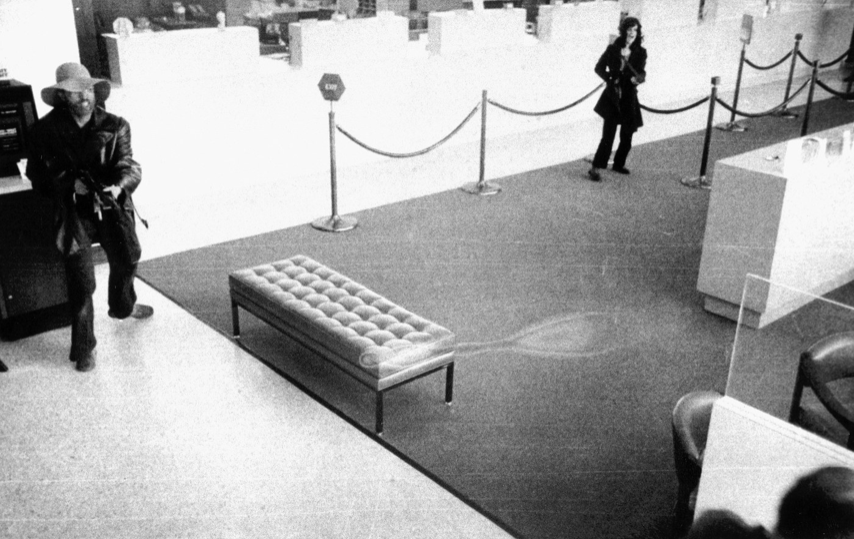

Hearst famously was seized from her Berkeley apartment by the Symbionese Liberation Army, and after some time in captivity, she appeared at a bank robbery carrying a gun and announced that she had “joined the revolution” and was taking on the new name Tania.

The latest book, Patricia Hearst: Queen of the Revolution by Gregory Cumming and Stephen Sayles, sadly continues the recent fascination with Hearst — and not the politics that created and were transformed by the kidnapping. That’s too bad, because what happened to all of us in the Bay Area during and after the kidnap is a far more interesting story.

Queen is the second book published in the last three years on the subject. Jeffrey Toobin, legal analyst for CNN and The New Yorker, published his American Heiress: The Wild Saga of the Kidnapping, Crimes and Trial of Patty Hearst in 2016. Like Cumming and Sayles, Toobin choose to focus on Hearst. While Queen is simply a rehash of previously published information with no new or original material, Heiress does offer readers a fine bit of reporting of the 1976 trial of Hearst, with Toobin doing his usual competent job of narrating court room maneuvers for both defense and prosecution lawyers. Queen devotes its final single page to “the trial and its aftermath.”

At an essential level one wonders why either recent book was even written, as both rely for description and explanation, especially of the political context, on two previously written classics on the subject: the 1976 The Life and Death of the SLA, by Pulitzer Prize winner Les Payne, Tim Findley of the Chronicle and Carolyn Craven of the old KQED Newsroom, and the 1977 The Voices of Guns by Vin McLellan and Paul Avery of the Chronicle and Examiner. Neither new book, with the exception of the trial narrative portion in the Toobin book, covers events in any great detail not covered in Life and Deathand Voices. Queen like Heiressrelies heavily on the two older books for the San Francisco context of the story with Cumming and Sayles citing either or both a whopping 147 times (in 162 pages of text!) while Toobin cites them some 30 times.

The most recent books include no new information on the impacts of the events of the fall and spring of 1974 in the subsequent political history of San Francisco, although both Life and Death and Voicesare full of such discussions up to the late 1970s.

That’s unfortunate – because there are some fascinating and important political events linked to those months that resulted in a historic shift in San Francisco politics. They are centered on the demand by the SLA that Hearst, to ransom his daughter, fund a massive million-dollar free food giveaway, and the period from February to March 1974 when the giveaway was headquartered in the old block-long Del Monte cannery building between 3rd and 4th along Mission Creek in San Francisco’s China Basin (now called Mission Bay).

Those two months saw the unplanned (certainly by the SLA) convergence of important elements of what would become a community-based coalition and a locally based media able and willing to cover it that transformed the politics of the city until the dawn of the 21st century.

The fractured left sects that dominated politics in Berkeley in the early 1970s were based upon a rootless and baseless population of middle-class white kids — the “bourgeoisie lumpen” — seeking identity and authenticity in their lives through essentially invented politics based upon theory and identity.

This was especially true of the “prison reform” movement based in the East Bay, from which the SLA sprang. This was before the era of mass incarceration and the movement was dominated by the theory that “authentic” revolutionary leadership would come from heroic individuals tempered by the life of crime. It fundamentally confused the “underworld” with the “underground.”

Unlike the suburban East Bay, San Francisco was an actual big city with actual neighborhoods in which real people lived and worked, often under tremendous pressure. It had absorbed the media-invented “hippie invasion,” and after the great “hippie migration” to the countryside in 1970, lead by Steve Gaskin, the city transformed hardy remnants into various community-based movements around the essentials of urban life: housing, food, and community control over development.

San Francisco neighborhoods fought for their very survival against both freeways and redevelopment, and had learned the hard lessons of unity and coalition, something the left sects in the East Bay simply never had to address.

No one here had heard of the SLA, and many were sure it was an example of the FBI’s playing the deadly game of COINTELPRO revealed in 1971 by anti-war protestors’ burglary and subsequent publication of the FBI’s counter intelligence program files aimed at both anti-war and black led political organizations. The Black Panther Party (itself heavily infiltrated by FBI informants) and many others on the left openly questioned the SLA’s “authenticity.”

But the fact remained that Randolph Hearst, Patty’s father, had agreed to put up the money for a multi-county food distribution demanded as part of the ransom for his daughter. He, of course, knew nothing of this world nor did he get any help from his “class” brothers who turned their backs on him, only willing to sell him the food he needed.

Then Gov. Reagan and Mayor Alioto (both endorsed by the Hearst newspapers) openly criticized the effort and offered no assistance.

The first food giveaway was a disaster. The trucks arrived, and the staff panicked when they were rushed by crowds and ended up throwing the food at the people — all the while being filmed by Hearst’s rival media outlets with glee.

The SLA demanded that a “community food coalition” be placed in charge of the next giveaway under the leadership of the Western Addition Project Area Committee, a legally required community oversight body of the urban renewal program in the Western Addition. Again, Hearst complied.

WAPAC had just been taken over by a set of young community activists in the Western Addition, many with ties to the Black Panther Party. Originally conceived as a Redevelopment Agency counter to the Western Addition Community Organization (WACO), which had won the first major decision against urban renewal in the US in a precedent setting case in 1968 causing the re drafting of the redevoplment area plan in the Western Addition in a way that required re-housing thousands of African Americans, WAPAC itself had been transformed from an agency ally to the opposite by a successful organizing campaign that resulted in the election of an actual community controlled slate.

Under WAPAC’s leadership, community activists in the Mission, Potrero Hill, the Haight-Ashbury, Nihonmachi, and Chinatown were brought into the community coalition to organize food distributions in those neighborhoods. Over the next six weeks, four more distributions were held, each without incident, and nearly 100,000 boxes of food were given out. The last one included sites from Santa Rosa to Santa Cruz as well as San Francisco, Oakland and Berkeley.

And it was then a certain unexpected set of relationships were formed that set San Francisco politics in a new direction.

The only public official willing to provide immediate and useful support to Hearst was then-State Senator George Moscone. Moscone had just finished a series of hearing on hunger among farm workers in the Central Valley and had an experienced and knowledgeable nutritionist on staff. He provided her to the food program and she immediately improved the quality of the food being purchased. Moscone spent some time at the China Basin building getting to know some of the community activists who were running the program.

A year later he came back to them when he ran for mayor. A year after that he transferred federal money away from redevelopment and began to fund a number of community based non-profit housing providers to build affordable housing without displacement in neighborhoods in eastern San Francisco.

Within a year, most of the groups in the food distribution realized that they had it on the ground. They formed the San Francisco Housing Coalition, with an expressed aim of building the capacity of community based and controlled groups to become nonprofit affordable housing developers. This group, later creating the Council of Community Housing Organizations, has developed more than 30,000 permanently affordable homes mainly for folks earning 60 percent or below AMI.

In 1976 an electoral coalition, San Franciscans for District Elections, made up of many of these same groups, drafted and waged a winning campaign, strongly supported by Mayor George Moscone, to create a district-elected Board of Supervisors. That distinct elected board passed rent control and limited condo conversions of existing apartments, saving the homes of tens of thousands of San Franciscans.

Under the Moscone Planning Commission, curbs on high rise office construction downtown and major hotels in the Tenderloin were imposed and a policy of “affordable housing exactions” were designed. While stalled after the assassination of Moscone, and the mayoral ascention of Dianne Feinstein, the policies were finally passed in 1986 as Proposition M by the voters over the active opposition of Feinstein and are still in place (but greatly weakened by the neoliberal policies of both the Newsom and Lee administrations).

It has been said that “In times of difficulties, we must not lose sight of our achievements.” It is difficult to believe that such a San Francisco existed, given today’s emphasis on feeding the endless development demands for the new coalition dominating public policy — the techo-real estate coalition — resulting in the greatest displacement pressure here since the Spanish landed on top of the Ohlone.

But the network of community relationships and potential for powerful collations still exist, as witnessed by last Novembers victory against these very forces in Proposition C.

Where is a good kidnap of a media heiress when we really need one?

UPDATE: Diego Aguilar-Canabal writes:

I read Calvin Welch’s piece with great interest today, but the part where he suggests there were no freeway revolts in the east bay is incorrect. Berkeley residents successfully opposed plans to build a freeway at Ashby Avenue: https://enf.livejournal.com/124467.html

West Oakland’s black community did oppose freeway construction in the area during the period of destructive “urban renewal” — lacking the political capital of whiter areas, they were not successful. This is described in the book “American Babylon” by Robert Self.

Welch responds:

I appreciate Diego’s comments and certainly do not disagree.

What I was trying to say was that the folks swept up in the SLA food distribution in San Francisco were BOTH “movement” organizations (the anti-war, police reform, pro-feminist, civil and human rights movements to list but four) AND neighborhood based community activist organizations with “roots” in urban neighborhoods as opposed to the more common “placeless” ideological organizations across the Bay. But perhaps that’s my “San Francisco exceptionalism” showing.