If you know where to look, San Francisco’s Tenderloin is still full of buildings that, a century ago or more were built to be storage facilities for film reels whose early motion-picture stock was highly flammable. Too much so to keep long in hot projection booths, so there was a busy commerce having them couriered back and forth, between theaters and the nondescript structures, whose extremely thick cement walls were designed to contain any potential fire.

Film projection hasn’t been such risky business in a long time. In fact, nowadays it seldom involves actual film at all. Nonetheless, the local screenings we’re highlighting below over the next 10 days or so turn the clock back to when cinematic activity did involve heavy cans of celluloid—hopefully, none of which turned incendiary.

The earliest flashback among them is BAMPFA’s new series “Silent Cinema Pioneers: From Alice Guy-Blache to Lois Weber,” which runs Sat/14 through September 25. In its first couple decades or so, the film medium was assumed by many to be a passing fad, and by many showbiz professionals to be beneath their dignity. Ironically, those dismissals opened doors to women that stayed shut in other creative fields—until of course, men realized movies were here to stay, at which point they largely pushed female directors out. Two giants of the silent era—though their careers were well over by talkies’ arrival—were French Guy-Blache and American Weber, prolific entrepreneurs who were pioneers on myriad fronts.

The former was involved in the nascent industry as early as 1894, and lived until 1968—nearly a half-century after quitting the business, amidst the collapse of the studio she’d founded. Her influential-yet-long-forgotten contributions are appreciated anew in Pamela B. Green’s documentary Be Natural: The Untold Story of Alice Guy-Blache, which plays Sat/14 and Fri/20. In between those two showings, on Wed/18, there’s a program of some of her surviving shorts (dated between 1901-’13) plus two chapters from Louis Feuillade’s famed 1915 surrealist serial Les Vampires. On Wed/25, there’s a double bill of that same year’s The Cheat, an early Cecil B. DeMille hit that shockingly hinged on a socialite’s sexually charged interracial alliance with a rich Japanese man (the great Sessue Hayakawa); and the next year’s Where Are My Children?, which demonstrates Weber’s own envelope-pushing interest in dramatizing taboo social issues.

With sound cinema, risque screen content that had once gone unspoken seemed more shameless than ever—at least to our nation’s moral watchdogs—which in 1934, led to enforcement of the restrictive Production Code. But for a few years there, movies were racy and then some, if still mostly dwelling in the realm of innuendo and (sometimes-barely) clothed players. The Roxie is commencing an occasional series of films from this now-treasured period, titled “Wild, Weird, Wicked: Films From Before The Code,”; this Wed/5 with Mervyn LeRoy’s 1932 Three on a Match. It has Joan Blondell, Ann Dvorak and Bette Davis as grade-school acquaintances who cross paths again in adulthood—when the “bad girl”; is making good, and the rich one proves most likely to hit the debauched skids. (Neither party is Davis, whose thankless character gets almost nothing to do.)

Cramming a whole lot into 63 whirlwind minutes, Match does not leave out maternal neglect, drug abuse, kidnapping, suicide, or Humphrey Bogart as a late-arriving goon. Upcoming (though not yet fixed to dates) are bizarro Karloff-Lugosi horror The Black Cat (which we recently wrote about here), Blondell again plus Barbara Stanwyck and Clark Gable in 1931’s Night Nurse, and the next year’s Island of Lost Souls, a lurid first screen version of H.G. Wells’ fantasy The Island of Dr. Moreau. Info on the whole series is here.

Hollywood got hardboiled again, to the extent that censors allowed, about a decade later with the advent of the genre we now call film noir. The Stanford Theatre is holding a two-month retrospective of movies in that idiom, combined with those produced in the 1940s by Val Lewton—whose psychologically complex, noirishly styled thrillers pushed horror in very different directions from the campy concurrent likes of Frankenstein Meets the Wolfman. Running this Fri/6 through November 10, the 38 features being shown include familiar classics (The Maltese Falcon, Double Indemnity, Out of the Past), cult favorites (Gun Crazy, Nightmare Alley), directors who peaked in the form (Preminger, Lang, Ulmer), and stars who did likewise (the blond duo of Ladd and Lake, femme fatale Joan Bennett, etc.)

The Lewton films, directed by several rising talents including future West Side Story and Sound of Music maestro Robert Wise, remain remarkable—among them the original Cat People, The Body Snatcher and I Walked With a Zombie—all the more so for having been made during such a short period, between 1942 and 1946. After that, studio politics and ill health sadly curtailed his activity, until a premature death in 1951 at age 46. The entire Stanford schedule is here.

Back at the BAMPFA in Berkeley, another series starting this Fri/6 offers the medium an offer to navel-gaze: “Cities & Cinema: Los Angeles”; is a survey of features that offer particular insight into that amorphous semi-industry town’s many overlapping identities. It begins with the noirish 1930s flashback of Polanski’s 1974 Chinatown. Specific ethnic communities are explored in Kent Mackenzie’s 1961 The Exiles (Native American), Charles Burnett’s 1977 Killer of Sheep (African American), Robert A. Nakamura and Duane Kubo’s 1980 Hito Hata: Raise the Banner (Japanese American) and Patricia Cardoso’s 2002 Real Women Have Curves (Latinx).

European directors are strangers in a very strange land in Franco Rossi’s 1962 Smog, Jacques Demy’s 1969 Model Shop and Agnes Varda’s 1968 Lions Love. The town’s racial co-opting of jazz is probed in Larry Clark’s 1977 Passing Through, and not so much in Damien Chazelle’s La La Land almost 40 years later. Pat O’Neill’s 1989 Water and Power is an experimental nonfiction that, like Chinatown, exposes LA’s problematic history around water appropriation and growth. Full info on the series, which runs through October 3, can be found here.

Urban life seems reassuring alongside the nightmare of inbred nowheresville perversity found in Tobe Hooper’s The Texas Chainsaw Massacre—another big hit of 1974, though unlike Chinatown, not one Oscar was inclined to notice. With its uniquely berserk, diseased atmosphere, mixing black comedy and sheer terror so vividly it seemed excruciatingly violent (though your mind is playing tricks—there’s almost no onscreen gore), this stab at commercial success by a filmmaker whose prior hippie opus Eggshells no one saw endures as a stone cold genre classic. I will never forget, or quite forgive, my college film professor assigning a campus screening to our class. He sat unnoticed behind me, and apparently greatly enjoyed my agonized squirming throughout.

There have been umpteen imitations, remakes, and sequels since, some interesting in their own right, but none a patch on the original. In honor of the still-fresh wound Chainsaw inflicted on the global moviegoing consciousness, the Balboa is giving it a 50th-anniversary full week’s run starting this Fri/6.

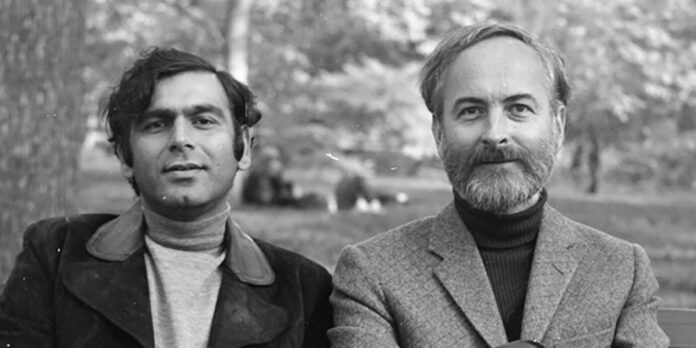

At the opposite end of the cultural scale—not so much in terms of quality but rather in audiences loathe to overlap with each other—lies the ouevre of Merchant Ivory. Stephen Soucy’s documentary of that name examines the life and legacy of a very long-running creative partnership that also encompassed writer Ruth Prawer Jhabvala and composer Richard Robbins. Among its surprises are the revelation of some very complicated private relationships within and beyond that quartet—the titular semi-closeted gay couple were not, well, exclusive.

Somehow Berkeley’s own Ivory and Bombay-born Merchant became inextricably associated with literature-derived English costume pieces, a realm in which they did their most popular and perhaps finest work (Howard’s End, Room With a View, Remains of the Day). But the 43 films they produced over 46 years’ course ran a much wider gamut, from early features shot in India for western audiences (like 1965&’s Shakespeare-Wallah) to stabs at Picasso, Thomas Jefferson, and Tama Janowitz.

You can’t blame this portrait for focusing primarily on the successes, though I’d have liked at least a little attention paid to that weird 1970s stretch when they were “finding themselves” via such oddities as the allegorical Savages and studio-interfered The Wild Party. But there’s more insight than you’d expect here, with Ivory (the quartet’s last survivor) drilled about the company’s less scrupulous financial practices. Collaborators interviewed—including Vanessa Redgrave, Hugh Grant, Emma Thompson, Rupert Graves, Helena Bonham Carter and many more—don’t hold back either, though all remain very grateful for the experiences had under MI auspices. Whether you adore all their movies, admire just a few, or renounce them as big-screen Masterpiece Theater, Merchant Ivory provides an absorbing and unpredictable peek behind a curtain. It opens Fri/6 at SF’s Opera Plaza Cinemas.

A few early 1980s curiosities very far from the upscale likes of A Room With A View will also be excavated for your local viewing pleasure after the weekend. I have a very faint, probably faulty memory of previously seeing 1982’s Turned On, a release from star Al Parker’s Surge Studios during that twilight period before AIDS laid siege to the gay porn industry (Parker would die from it a decade later), and the video revolution killed off nearly all imaginative adult content in favor of sheer churned-out quantity.

Directed by Steve Scott, this “all-male” XXX feature has the producer-marquee name as a bathhouse patron searching for an elusive quarry, though he certainly finds time for others en route. It’s purported to be a surreal phantasmagoria comparable to Wakefield Poole’s 1972 Bijou—a movie that, alongside Fred Halsted’s L.A. Plays Itself the same year, is probably the closest the form ever came to cinematic art. Turned On’s soundtrack by Man Parrish (as “Forbidden Overture”) had its own impact, well beyond the porn circuit, and this screening on projected VHS also celebrates that music’s recent reissue by SF-based Dark Entries Records. The 18-and-over-only show plays Thu/12 7:30pm at SF’s 4 Star Theatre.

That same night sees the first of several Roxie screenings of another 1982 obscurity, The Time Masters from French animator Rene Laloux, whose 1973 Fantastic Planet was a staple of campus and midnight showings for years. Yet he struggled to pull together a followup, and this co-production with Hungary suffered from budgetary straits—Jean Giraud aka Moebius, who designed and co-wrote it, said “When I saw the film for the first time, I was ashamed; [it was] incredibly cheap.” Still, he credited it with “a flavor, a charm” and this newly restoration maximizes those plus points. Focused on a child’s adventures on a hostile planet his parents died crash-landing on, it’s a juvenile story with some weird adult ideas and impressive background visuals. More info here.

Last, and probably least, there’s Caligula: The Ultimate Cut, which plays the Vogue next Fri/13-Sat/14, following some Alamo Drafthouse dates announced too late for us to cover. After the “porn chic” vogue triggered by Deep Throat, some folks thought graphic, “real” sex would inevitably become a part of the regular movie mainstream. Eager to push that forward was Penthouse Magazine tycoon Bob Guccione, who’d already dabbled in the film business. He hired no less than Gore Vidal to write the screenplay for a historical epic of Roman Empire decadence, and director Tinto Brass on the basis of his Salon Kitty, the most elaborately produced of the sexed-up Nazisploitation features that followed kinky international hit The Night Porter.

Things had already started going south when filming began in 1976. Guccione rejected Vidal’s script as having too much gay sexuality; Brass’ rewrite prompted the author to disown the entire project. Then after principal photography ended, Guccione surreptitiously had hardcore footage shot with porn actors (some of whom had been extras on the set), then inserted into the film—which Brass then disowned. Post-production dragged on so long, Caligula wasn’t released in Italy until the end of 1979, and in the US until early the next year, encountering censorship battles everywhere. But everyone agreed: It was a lumbering, bizarrely anti-erotic mess. Albeit one whose very scandalousness of existence—whoever expected to eyeball both porn and Sir John Gielgud in the same 2.5 hours?—resulted in a degree of box-office success, itself still disputed.

As the mad emperor, Malcolm McDowell seemed to be hammily goofing. As his predecessor, Peter O’Toole just bellows, in ridiculous makeup. Two actresses cast primarily for their willingness to “do nudity,” Helen Mirren and Teresa Ann Savoy, acted as best they could—which meant admirably and hardly, respectively. Brass, who’d soon move permanently into softcore as the ass-man answer to breast-o-phile Russ Meyer, directed this labored spectacle no better than he had Salon Kitty. (Though admittedly that film, too, was released in a form he hadn’t consented to.) The production values are palpably high, with some remarkable sets by Danilo Donati. Yet the nicest thing one can say is that while it certainly looks like it cost a lot of money, it was made by people who evidently had no idea how to properly exploit such assets. Caligula is a lavish, disconnected costume party, a series of diorama-like tableaux with naked people floundering around in the background. There’s no shape to individual scenes, much of a narrative arc or basic story even. Rarely does a finished film so clearly reflect behind-the-scenes disarray: This big, expensive ship seldom feels like anyone is steering it.

The Ultimate Cut, which is a full three hours long, is really a new film: Comprised entirely of alternate takes drawn from 90-plus hours of original camera-negative footage, supposedly hewing closer to Vidal’s script. (But since his script was drastically revised before shooting began, what does that even mean?) The hardcore inserts, which looked grainy and superfluous 45 years ago, are gone. Some of the over-the-top violence is now also more restrained, or missing entirely. More regrettably gone are interpolated musical themes utilized after official score composer Bruno Nicolai joined the lineup of participants disowning the release version.

But while it has moments of interest—or at least, potential—the reconstructed Caligula remains a stillborn mess, at once tawdry and lethargic. A detailed making-of chronicle would be far more rewarding than the film itself can ever be. It’s one of those movies that morbid curiosity demands must be seen, then the grim reality of watching prevents from being any real fun at all. (Not unlike another 1980 wonder, Can’t Stop the Music.)

Whatever clashing visions Vidal, Guccione, Brass, and anyone else might have intended to realize never made it before a camera. What did get shot was the creative equivalent of a circular firing squad, everybody’s vision extinguished. Any way you re-cut it, Caligula is a celluloid funeral pyre, a smoldering ruin. 44 years after walking out the first time (I think), I couldn’t resist taking a second look—and now can die a happy man never getting anywhere near this godawful dud again.