State Sen. Scott Wiener is promoting his housing bill, SB 50, as an example of environmental progress, since the measure is pushing transit-oriented development – building new housing near existing transit lines.

But how does that work when there is only a marginal functioning transit system in a city? Don’t expect any answers from Wiener – or, if his history as mayor is any indication, Governor Newsom.

Last week’s Muni meltdown has been a long time coming and the least responsible person for it is the guy who is going to take the fall: Ed Reiskin. Put simply, public transit in San Francisco has been underfunded for decades as administration after administration has sought massive growth in the commercial sector that has simply overwhelmed Muni without increasing its capacity to meet the demand of that growth. But underfunding of transit is also a regional and statewide reality as well.

Based upon public transit (not freeways, roads, tunnels and bridges which are also falling apart) capital plans at the state, regional and local level we are now facing a combined $204 Billion “shortfall in funding transit that simply cannot continue given the insane rate of growth in the job sector in the region and locally.

Current Projected Transportation Deficit State, Regional and Local: $204B

| Project | Cost | Identified Funding | Current Projected Deficit |

| Bullet Train Complete | $77.3B | $12.7B | $64.5B |

| Regions Needs to 2040 | $428B | $309B | $119B |

| Muni needs to 2045 | $31B | $10B | $21B |

Sources: Bullet Train, State Auditor Report 2018-108, November 2018; Regional Need, Plan Bay Area 2040, July 2017; Muni, SF Transportation 2045 Task Force Report, Jan. 2018

In San Francisco, the shortfall in funding is complicated by an unwillingness to link future growth in commercial and now, with SB50, market rate housing production to increase funding for transit, a lack of political will in confronting the transit killing aspects of the “new economy” (Uber and Lyft, tech buses and the dramatic increase in truck deliveries to residential locations from Internet shopping) which drive up transit costs and lower transit travel times, and an organizational structure of the SFMTA that places transit operations three levels down the organizational chart (SFMTA Organization Chart).

Wiener refuses to fund Muni

Help us save local journalism!

Every tax-deductible donation helps us grow to cover the issues that mean the most to our community. Become a 48 Hills Hero and support the only daily progressive news source in the Bay Area.

In 2015, San Francisco sought to create a linkage between commercial office and market-rate housing development and the true cost to the city of providing transit services to that new development.

A Transit Sustainability Fee was examined in a May, 2015 TSF nexus study, which sought to document the link between job and housing growth and transit costs. That study found that the transit costs of residential development was some $30.93 per square foot of new development. The cost for commercial development, mainly hotels and office buildings, was a whopping $87.42 a square foot.

That’s how much money Muni needed to serve those new homes, hotels, and offices.

Yet, Mayor Ed Lee and his pro-business allies on the Board of Supervisors, lead by Supervisor Wiener, simply refused to follow the report and instead, pulling numbers from thin air, proposed a fee much more to the liking of their patrons: $7.74 a square for residential and $24.04 for commercial development, only about one quarter of the true costs. 48 Hills covered the key votes in great detail (48 Hills coverage of 2015 hearing).

Wiener, the year before, in order to establish his pro-transit cred to the inattentive and casual observer, had made a big show of placing a charter amendment on the ballot that required Muni’s budget to be linked to annual population growth and boldly required that “75 percent shall be used for system improvements” and “25 percent for capital improvements” of “any increase resulting from the adjustment.” What was not so boldly announced was that there was no new revenue source stipulated for this “adjustment.” The only way Muni’s budget would be increased was at the expense of other general fund programs — pitting Muni against children, affordable housing and homeless services. The TSF could have been that source, but Wiener chose simply to protect the interests of developers, not Muni riders.

Ed Lee ignored Muni

Ed Lee basically ignored Muni. His attention seemed to be focused on making the streets safe for tech shuttles and TNC’s (the bureaucratic name for Uber and Lyft) — both of which impeded the flow of Muni with tech shuttles allowed to idle in Muni stops while Muni riders had to walk around them and the TNCs simply crowding the streets of downtown San Francisco, increasing the travel time of Muni buses slowed in traffic.

City departments under Lee simply ignored the impacts on Muni of the a steeply rising number of delivery trucks delivering internet purchases. The Planning Department disclosed to the Board of Supervisors that it doesn’t even consider delivery trucks when analyzing high-density residential development, even along transit corridors.

Lee’s single revenue proposal for Muni, other than cutting the fees for transit for developers, was placed on the ballot as Proposition K in 2016 (his last election) and it was a sales tax! Taxing the poorest San Franciscans to pay for a crucial service key to the out sized profits of developers was simply unsupportable by the great majority of San Franciscans, and Prop. K was massively rejected by 65 percent No vote.

By the end of Lee’s administration, ridership on Muni was in decline, with many of the new tech workforce simply refusing to ride, preferring private hailing services to public transit. Muni ridership declined from an average of 745,000 a day in 2016 to some 703,000 a day in February of this year (MUNI ridership).

At least Lee didn’t base his political advancement on baiting Muni and raising Muni fares and parking fines as his only revenue ideas on funding transit. That’s what Newsom did.

Newsom made riders, not developers, pay for Muni

In 1999, after a “Muni meltdown” in the fall just before the election, voters passed Proposition E placed on the ballot by the supervisors led by Supervisor Gavin Newsom. Newsom used the campaign to bash Muni claiming that it was “out of control” with “…late trains and buses, long delays in the tunnel, frequent accidents and dismal customer service” (sound familiar?)

Proposition E , it was promised, would “…reduce traffic by making transit a real alternative to the automobile…and ensure that Muni is fully funded to meet the transit needs of the City for years to come” (Voter Handbook 1999). Devised by SPUR and strongly supported by downtown business interests, Prop E combined Traffic and Parking with Muni and created a new commission, all appointed by the mayor and totally accountable only to the mayor. It would take a two-thirds vote of the elected Board of Supervisors to overturn a budget item or a route change adopted by the appointed commission.

Handing over total control to transit planning and operations to the Mayor’s appointed commission was called “taking politics out of Muni.”

Under Newsom, the city dramatically increased user fees, including traffic and parking fines, to fund city operations. Notably, he increased Muni fares twice: from $1.25 to $1.50 in 2005 and then to $2.00 in 2009, a combined 60 percent increase. Newsom had no other ideas on how to fund Muni and never placed a Muni revenue issue on the ballot.

Developers will pay nothing for Muni

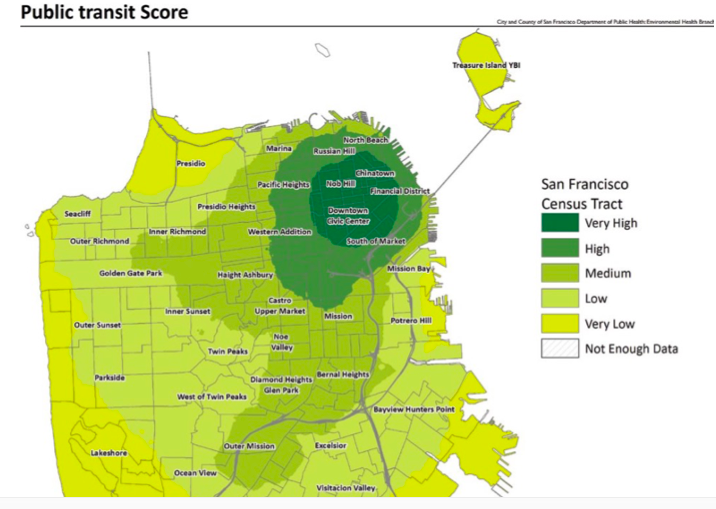

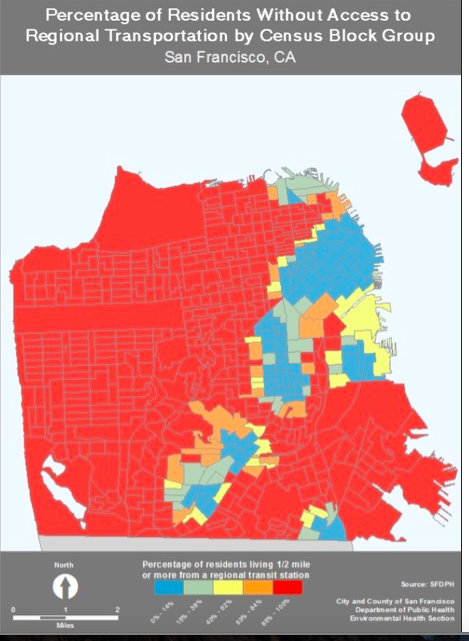

SB50 does not require developers exercising its generous density bonus along transit corridors to pay one cent to insure existing transit service will not be overburdened by the new high-density development. As Wiener well knows, AB50 is aimed at single-family-home neighborhoods in the southern and western portions of San Francisco (and in other cities). These neighborhoods have two significant transportation characteristics: They are the neighborhoods with the most car ownership per household in the city, and they have poor Muni service. One, it could be argued, is caused by the other.

Two maps, from the Department of Public Health (not the Planning Department who ignored the entire transit issue in its recent analysis of the “impacts” of SB 50, March 14 CPD SB50 Report) tell the story:

Moreover, SB50 does not prevent developers from building off-street parking in their developments even though our Master Plan calls for limiting parking structures along transit corridors; it simply limits the ability of cities toimposethe requirement. If a developer wants a parking garage for a 100-unit building along a transit corridor because he can’t sell a $2 million condo on the view floor without a dedicated parking space or the bank won’t finance the project without off-street parking, nothing in SB 50 prevents that from happening, as it supersedes local-land use requirements.

High density development proposed by SB50 has been sold as “transit-oriented development” but it lacks funding to maintain transit capacity and, by allowing developers to make decisions on where to place large parking facilities, creates the possibility of major car/transit conflicts further reducing transit use and effectiveness.

The saving grace for transit of SB50 is that it is, at its heart, a real estate hustle that is “speculator-oriented development” that will not result in much actual housing being built — which is why Wiener steadfastly refused of including actual language requiring a developer who receives a density bonus from ever having to actually build anything. There is no “use it or lose it” requirement in the bill, which is why Wiener was willing to let Marin and Sonoma county off the hook — counties that might have actually provided housing opportunities that would appeal to well-heeled San Francisco based workers and lessened the pressure on the city.

Muni’s problems are real and persistent. It needs massive funding and it needs a workable administrative structure which puts it at the center of a department.

We should look at a series of revenue measures such as congested pricing charging TNC’s a special fee for entering the transit critical central business district. We need to dramatically increase transit fees on new market rate housing and commercial to nexus studies levels. We need to create a new gross receipts tax on transit dependent existing businesses downtown and in the South of Market.

And then we need to repeal the out dated and poorly conceived 1999 Prop E and replace it with a Muni-centric department that puts transit operations at the very center of its activity, that increases drivers pay and training, recruiting in San Francisco high schools (as the Transport Workers Union proposed in 2018) and building a workforce that lives here and cares about the city.