The urban environmental movement, and much of the progressive politics of the past half-century, were born in San Francisco as a reaction to a few white men meeting in a hotel room and mapping out the post-War future of the city.

As the eminent urban planner and historian Chester Hartman explains in City For Sale, The Transformation of San Francisco, Ben Swig, the owner of the Fairmont Hotel, convened meetings in his penthouse suite in the 1950s with the heads of local industry and began making plans to turn San Francisco into the next Manhattan.

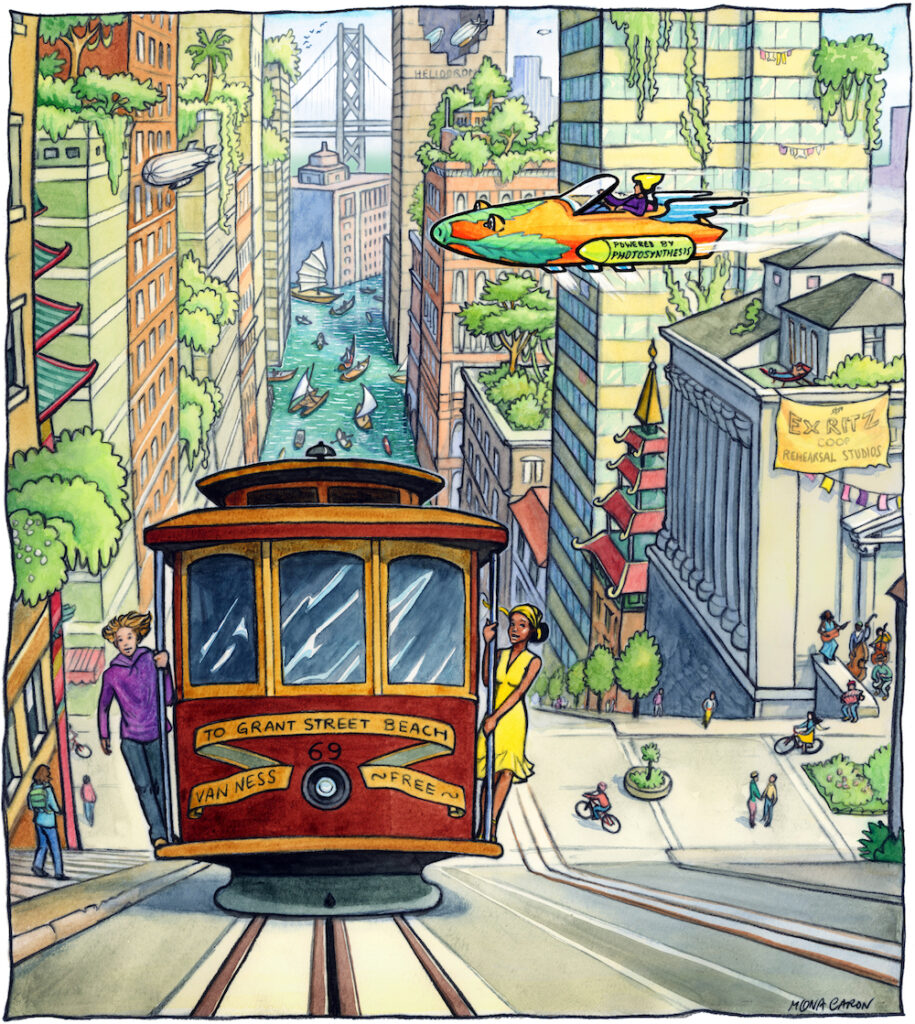

Image by Mona Caron, from the 2006 Bay Guardian Best of the Bay issue, imagining the city’s future.

Soma? That land, as the head of the Redevelopment Agency, Justin Herman, said, “is too valuable for poor people to park on.” So 10,000 low-cost SRO housing units were demolished to make way for the hotels and convention center that a city that would be the finance, insurance, real-estate and corporate center for the Pacific Rim needed.

The Western Addition? That space was needed for more upscale residents, so 50 square blocks were bulldozed.

Downtown? That was going to be the center of everything, so lots of highrise office buildings had to be constructed, so that tens of thousands of new white-collar workers could move to the city.

Blue-collar jobs? They were in the way. Manufacturing, printing, warehouses, light-industry – all of it had to go to make way for the new, bright, shiny, highrise office future.

Of course, along with that came higher housing prices, displacement, traffic, financial pressure (as the Bay Guardian showed in 1971, all this development paid less in taxes than it cost in services) and plenty of other problems.

And of course, the real-estate developers became very rich.

But the biggest problem is that nobody asked the people who lived in the city whether they wanted to be the corporate headquarters for the Pacific Rim, whether they wanted to be the next Manhattan. The plans were all done in secret, then launched bit-by-bit with the acquiescence of a series of mayors and supervisors and planning commissioners.

Nobody held a series of public hearing and asked: What kind of city do we want to be in 20 years – and for who?

This happened again, with less secrecy but no less political power, under the administration of Mayor Ed Lee, who decided that San Francisco should be the tech headquarters of the West Coast. He gave out tax breaks. He had “tech Tuesdays” where he met with companies and offered city help. He allowed tech startups (and big companies like Google) to violate local laws with impunity.

The impact was dramatic: Tens of thousands of evictions and forced relocations, the devastation of long-term communities, and the wholesale transformation of much of the city.

And again: I never saw a public hearing on the question of whether San Francisco should be the tech headquarters of the future, and whether that move would benefit the people who already lived here.

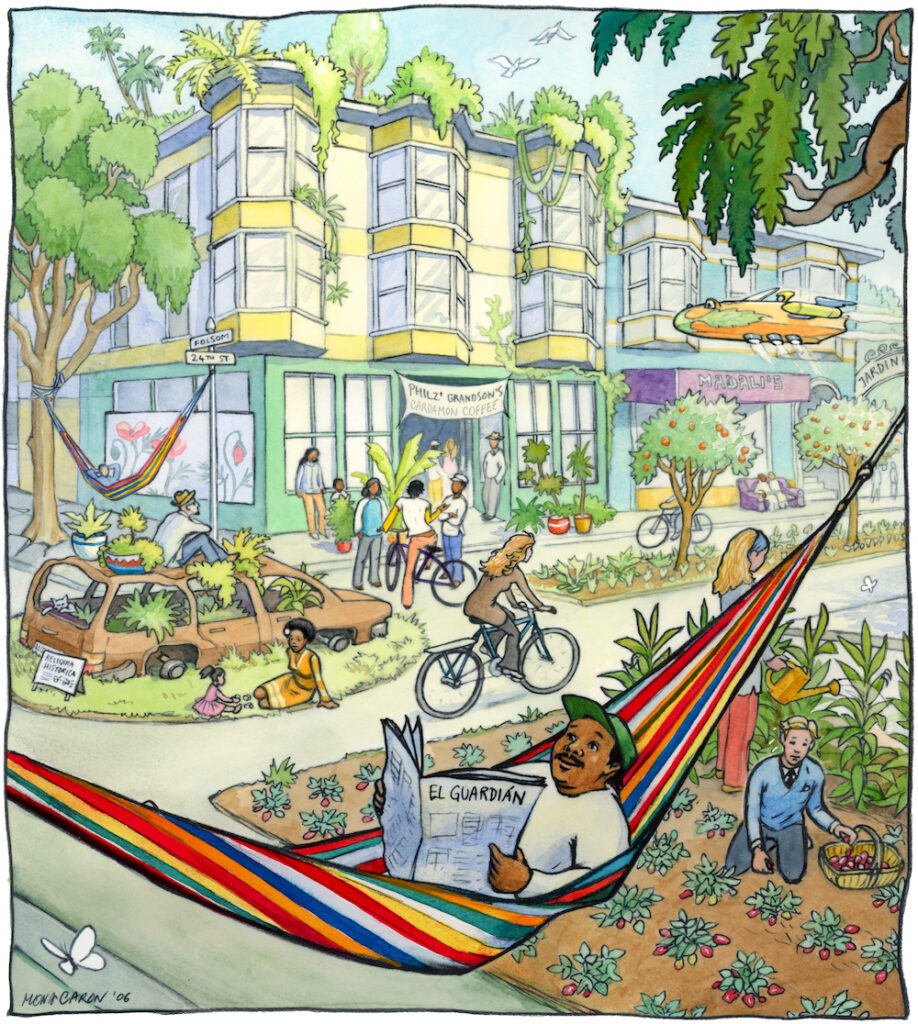

Image by Mona Caron.

Nobody knows what the post-COIVD local economy will look like. But we do know that remote work is here to stay, and we know that a lot of the tech workers who moved to SF in last boom are now leaving (for Bozeman, Montana, among other places.)

So commercial office rents are collapsing, and residential rents are also falling. (The Yimby argument that building more market-rate housing will cause prices to fall – the supply-side approach – never worked, but the demand-side seems to have some impact.)

The Chron’s latest story laments the trend:

With numerous tech companies like Twitter, Pinterest, Dropbox, Yelp and now Salesforce embracing remote work programs beyond the pandemic, the Bay Area’s status as the premier tech hub, along with its urban economic vitality, is in doubt. Empty streets and shuttered storefronts may linger even as some workers are vaccinated and return to offices if others stay home or leave the region entirely.

But let’s not go there so fast.

The “urban vitality” of San Francisco was more damaged than enhanced by the tech boom. The city’s status as “the premier tech hub” was not a good thing for most residents.

I heard the mayor and many economists rejoice that the city’s unemployment rate was so low in that era – but that was at best misleading and at worst a lie. Yes, tech jobs created “spin-off” jobs – but those were mostly in the service sector, and didn’t pay enough to afford the soaring housing prices that the tech boom created.

So new we are going to have some kind of reckoning – and instead of letting the private-sector and its allies in politics make all of the plans and decisions, maybe we ought to have a serious, inclusive, civic discussion: What kind of city do we want to be now, and for who?

What do the people who live in San Francisco need? What economic development will provide jobs for currently unemployed San Franciscans? Do we want to bring back blue-collar jobs (which may be entirely possible with the collapse of commercial real-estate prices)? Do we want to be a city driven by small business or by big corporations?

What should San Francisco look like in five years? In ten years? And how do we get there?

If the people who live here don’t have that discussion, and force our elected officials to have it with us, then the same forces of capital and power will do it for us. That’s happened over and over in the past. We now have a choice of whether it will happen again.

The Department of City Planning hasn’t done a lot of “planning” of late – it’s mostly processed permits for developers who “plan” the future. The Mayor’s Office hasn’t done a lot of work on economic and workforce development – except to support the private sector.

David Talbot makes the point nicely in a recent post:

To remake San Francisco, we shouldn’t rely on SPUR, SF.citi, the Chronicle editorial board or any of the other corporate brain trusts. As I’ve been arguing, we need to convene the broadest and most diverse array of local citizens in order to rebuild a truly livable city.

Yeah, like that.

Maybe it’s time for the Board of Supes to start convening a series of public hearings on the future of the city. There are so many brilliant people here who can help re-imaging San Francisco, so many creative thinkers who can talk about what sustainability means (and maybe it means slowing down growth).

Maybe some of those empty offices should become housing. Maybe instead of using corporate consulting firms, we should bring these folks in to help us.

COVID has changed everything – except, of course, corporate greed and wealth inequality.

But San Francisco, like all great cities, will survive – and now is the time, for once, to allow the people who live here to have a chance to do some real planning, for a better future. It’s out there.